Cookies

Introduction

Cookies allow websites to save data and maintain state information across HTTP requests, a stateless protocol. Web applications use cookies for several purposes, like authentication, fraud prevention and security, or remembering preferences and user choices. However, since their introduction in the mid-1990s, cookies have also played a dominant role in online tracking of web users.

Over the years, browser vendors such as Brave, Firefox, and Safari have imposed restrictions, partitioned, and removed third-party cookies. While Chrome initially appeared to follow in these same steps by announcing plans to block all third-party cookies, several delays and postponements later, Google eventually decided to keep third-party cookies unrestricted and let users decide to disable them in Chrome.

In this chapter, we measure and report on the prevalence and structure of web cookies encountered on the web pages visited by the HTTP Archive crawl of July 2025. The majority of these results, except when mentioned otherwise, are for the top one million (top million) most popular websites according to their rank in the Chrome User Experience report (CrUX) rank recorded in the HTTP Archive dataset at the time of the crawl. Results are also shown for both desktop and mobile devices although, in practice for this chapter we rarely observe any significant difference between the two types of devices.

Background

First up let’s get a common understanding of some of the terms used in this chapter.

HTTP cookie

When a user visits a website, they interact with a web server that can request the user’s web browser to set and save an HTTP cookie. This cookie corresponds to data saved in a text string on the user’s device and is sent with subsequent HTTP requests to the web server. Cookies are used to persist stateful information about users across multiple HTTP requests—which can allow authentication, session management, and tracking. Cookies are also associated with privacy and security risks.

First and third-party cookies

Cookies are set by a web server and can be of two types: first-party and third-party cookies. First-party cookies are set by the same domain as the site the user is visiting, while third-party cookies are set from a different domain.

Third-party cookies may be from a third party, or from a different site or service belonging to the same “first party” as the top-level site. Third-party cookies are really cross-site cookies.

For example, imagine that the owner of the domain example.com also owns example.net and that the following cookies are set for a user visiting https://www.example.com:

| Cookie name | Set by | Type of cookie | Reason |

|---|---|---|---|

cookie_a |

www.example.com |

First-party | Same domain as visited website |

cookie_b |

cart.example.com |

First-party | Same domain as visited website: subdomains do not matter |

cookie_c |

www.example.edu |

Third-party | Different domain than visited website |

cookie_d |

tracking.example.org |

Third-party | Different domain than visited website |

cookie_e |

login.example.net |

Third-party | Different domain than visited website even if owned by the same owner in this example (cross-site cookie from the same “first party” at the top-level site) |

Privacy & security risks

Cookies, while fundamental to allow the web to work, do pose privacy & security risks:

-

Web tracking. Cookies are used by third parties to track users across websites and record their browsing behavior and interests. In targeted advertising, this data is leveraged to show users advertisements aligned with their interest.

This tracking usually takes place the following way: third-party code embedded on a site can set a cookie that identifies a user. Then, the same third-party can record user activity by obtaining that cookie back when the user visits other websites where it is embedded as well (see also the Privacy chapter).

We note that first-party cookies can also be used for online tracking, methods such as cookie syncing allow bypassing the limitation of third-party cookies and track users across different websites.

-

Cookie theft and session hijacking. Cookies are used to store session information such as credentials (for example, a session token) for authentication purposes across several HTTP requests. However, if these cookies were to be obtained by a malicious actor they could use them to authenticate to the corresponding web servers.

If cookies are not properly set by web servers, they could be prone to cross-site vulnerabilities such as session hijacking, cross-site request forgery (CSRF), cross-site script inclusion (XSS), and others (see also the Security chapter).

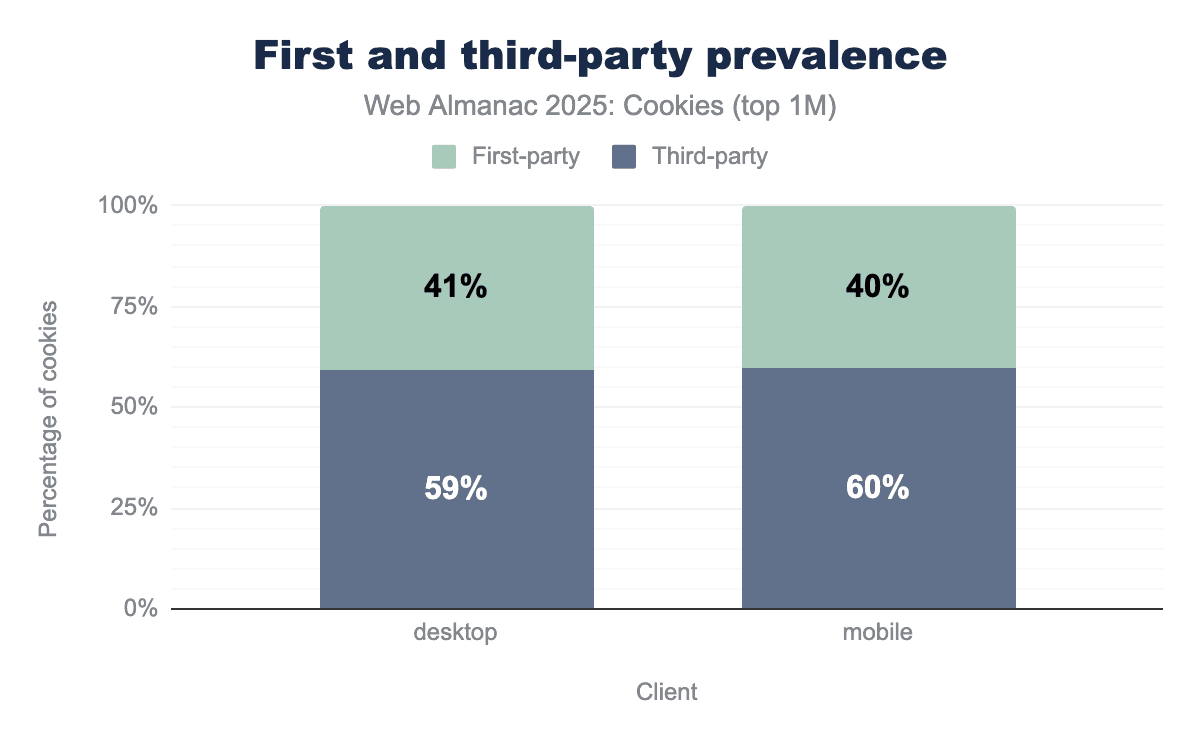

First and third-party prevalence

The overall prevalence of first- and third-party cookies on the top one million most popular websites from the HTTP Archive crawl of July 2025 is similar to last year’s distribution.

On both desktop and mobile devices, roughly 40% of cookies are first-party and about 60% third-party.

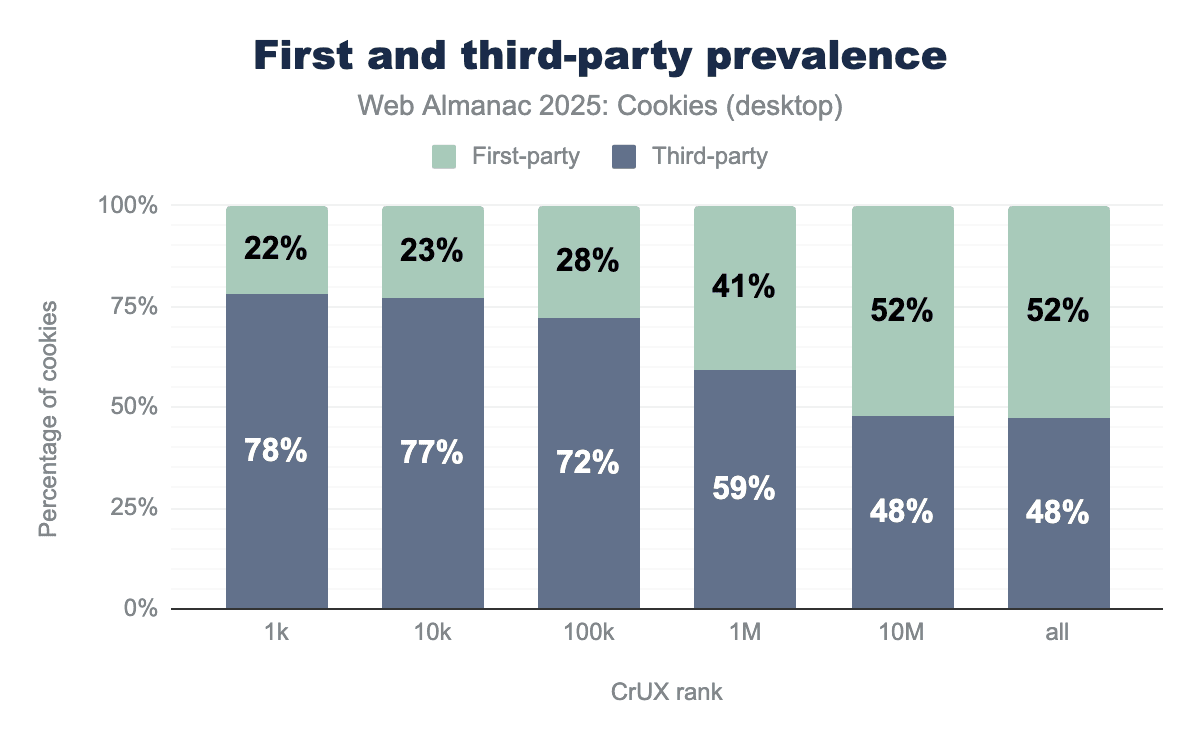

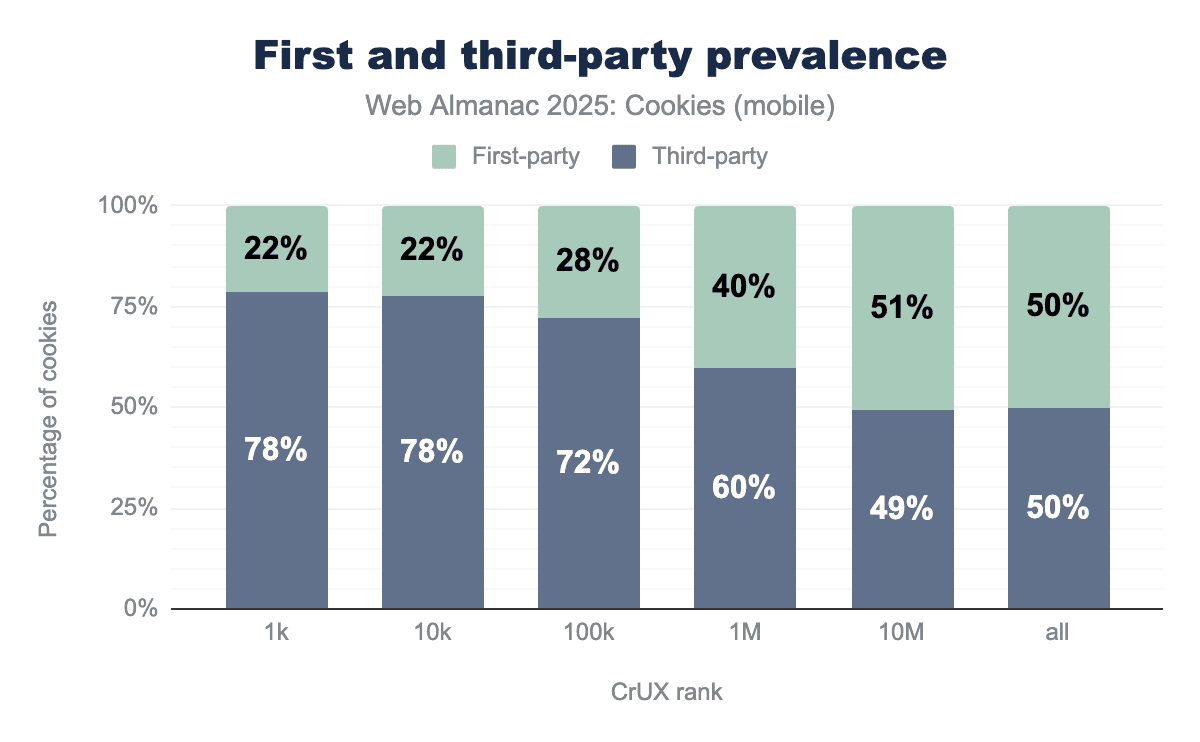

First and third-party prevalence by rank

We observe that the most popular websites set in proportion more third-party than first-party cookies: 78% of cookies are third-party on the top 1,000 most visited websites when it is just below 50% on the top 10 million. This may be explained by the fact that more popular websites also include more third-party content and scripts that in turn set third-party cookies to enable different functionalities.

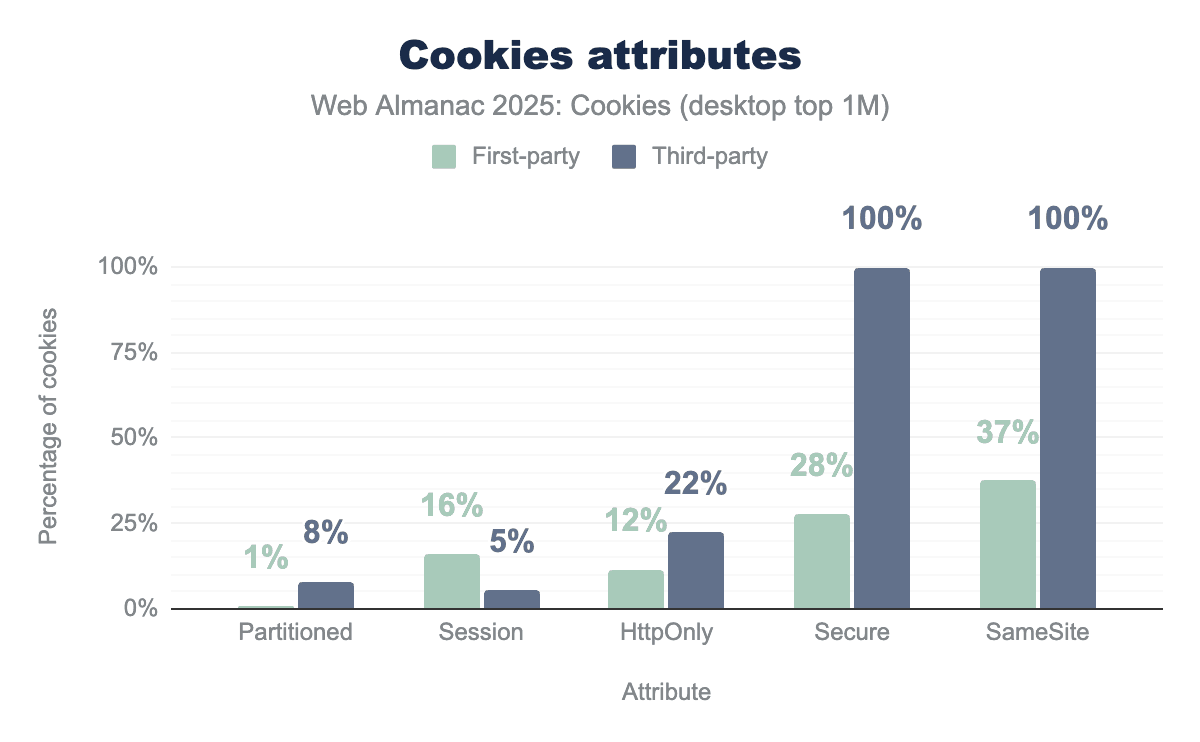

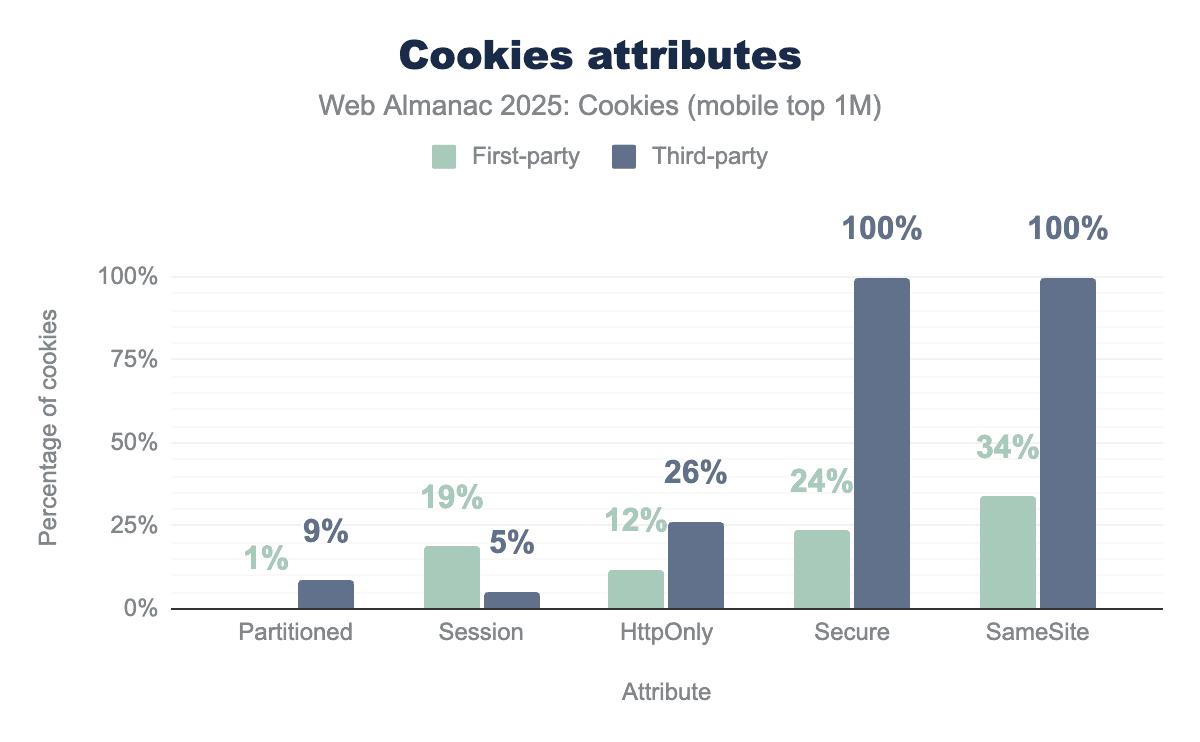

Cookie attributes

Partitioned. 19% of first-party cookies set their Session attribute, while this is the case for only 7% of third-party cookies. Finally, 12% of first-party cookies and 28% of third-party cookies use the HttpOnly attribute.Partitioned. 19% of first-party cookies set their Session attribute, while this is the case for only 5% of third-party cookies. Finally, 12% of first-party cookies and 26% of third-party cookies use the HttpOnly attribute.The data showcases the different cookie attributes for each type of cookies observed. Let’s delve into each of these.

Partitioned (CHIPS proposal)

On compatible browsers, partitioned cookies prevent third-party cookies to be used for cross-site tracking by placing them into a storage partitioned per top-level site.

Partition cookies on mobile pages.

In July 2025, nearly 9% of third-party cookies on the top million are partitioned. We observe here a slight increase in adoption of this relatively new attribute in comparison to the 6% of last year’s results.

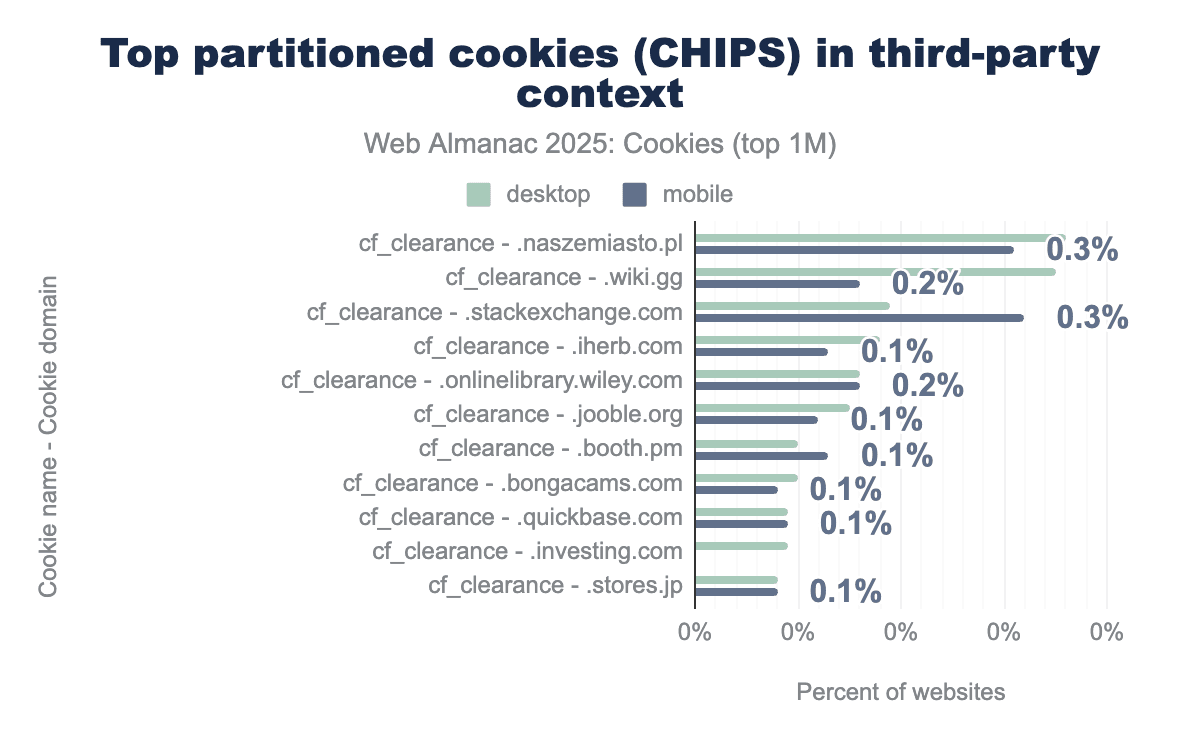

cf_clearance set by Cloudflare and is used for anti-bot challenge.The previous chart shows the 10 most common partitioned cookies (name and domain) found in third-party context on web pages in July 2025. Here, we observe a major change from last year’s analysis, indeed the overall usage of third-party partitioned cookies in 2025 appears to have plummeted to very low levels.

Interestingly, partitioned cookies that were somewhat predominant in 2024 (on about 9% of websites with partitioned cookies) are not present anymore; two of these cookies were set by YouTube and another one was the receive-cookie-deprecation cookie set by domains that participated in the testing phase of Chrome’s Privacy Sandbox. Instead, Cloudflare’s cf_clearance cookie accounts for the entirety of the top 10 most common partitioned third-party cookies in 2025.

So, in the past year YouTube appears to have altered how these cookies were set on youtube.com and on video iframes embedded on other websites. Potential reasons that could explain these changes include: incorrect setting, A/B testing, and more likely infrastructure or policy updates following Google’s announcements on the pause and then deprecation of Privacy Sandbox APIs, despite support for partitioned cookies (CHIPS proposal) still being continued.

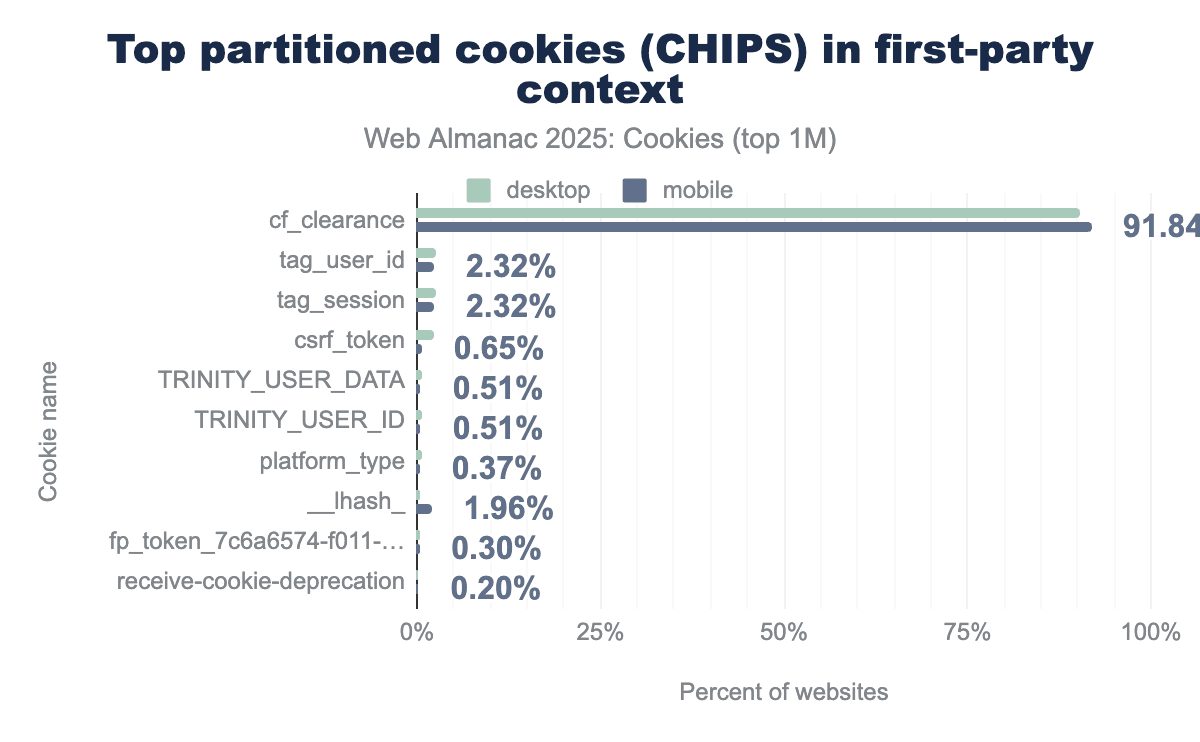

cf_clearance is set by Cloudflare on about 92% of pages with partitioned cookies, and is related to bot detection.In 2025, we continue to observe that 1% of first-party cookies are set as partitioned; this might be a bit surprising as the CHIPS proposal is mainly about partitioning third-party cookies, and even if it mentions a specific uncommon case for partitioned first-party cookies, the behavior requirement appears unclear in first-party context. One reason could be that some cookies are always set the same way—that is, the web server setting them is not distinguishing whether it is currently first-party or third-party.

In 2025, more than 90% of these first-party partitioned cookies are Cloudflare’s cf_clearance cookie related to bot detection. Comparing to 2024’s analysis, we remark that the first-party partitioned cookie receive-cookie-deprecation, set by domains participating in Privacy Sandbox APIs tests, is not as popular anymore. Perhaps, this observation can be explained by a pause or reduction of adoption of these APIs due to Google’s corresponding announcements in this past year.

Session

19% of first-party and 7% of third-party cookies are session cookies; temporary cookies only valid for a single user session that expire once the user quits the corresponding website they were set on, or closes their web browser, whichever happens first.

HttpOnly

HttpOnly cookies provide some mitigation against cross-site scripting (XSS) as they can not be accessed by JavaScript code (but are still sent along XMLHttpRequest or fetch requests initiated from JavaScript).

12% and a little more than 26% of first- and third-party cookies have this attribute set, respectively.

Secure

Secure cookies are only sent to requests made through HTTPS, same trend as last year here; while only 24% of first-party cookies set this attribute, all third-party cookies have to set it if they want to use SameSite=None (which they all do, see below).

SameSite

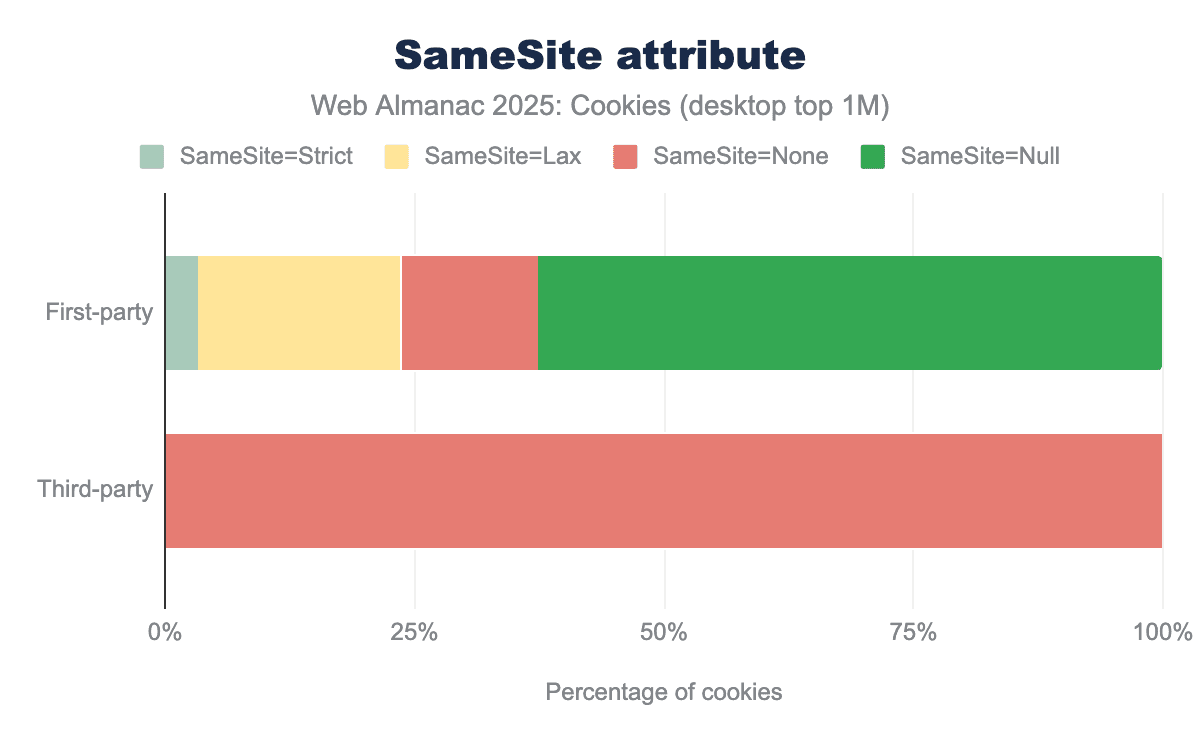

The SameSite cookie attribute allows sites to specify when cookies are included with cross-site requests:

SameSite=Strict: a cookie is only sent in response to a request from the same site as the cookie’s origin.SameSite=Lax: same asSameSite=Strictexcept that the browser also sends the cookie on navigation to the cookie’s origin site. On Chrome, this is the default value ofSameSiteif no value is set.SameSite=None: cookies are sent on same-site or cross-site requests. This means that in order to make third-party tracking with cookies possible, the tracking cookies must have theirSameSiteattribute set toNone.

To learn more about the SameSite attribute, see the following references:

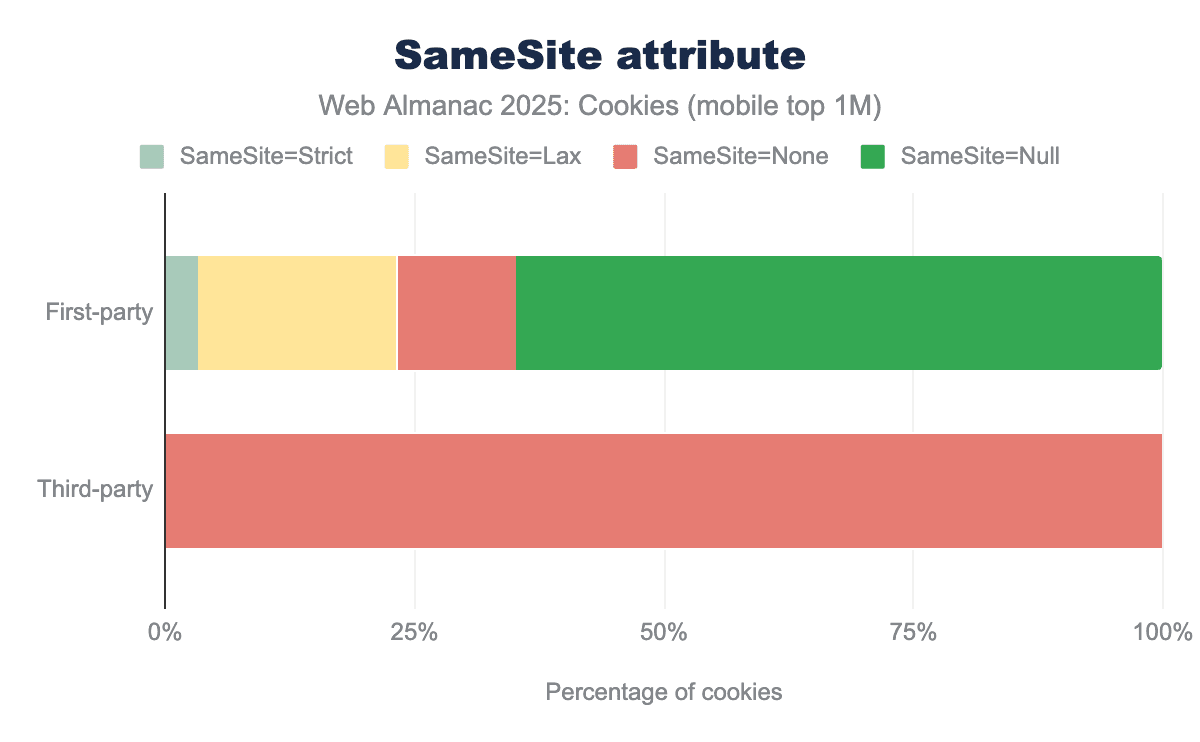

SameSite attribute and its value for both first-party and third-party cookies on desktop clients. 3% of first-party cookies set the SameSite attribute to Strict, 19% use SameSite=Lax (which is the default on Chrome), 11% set the value to None and 66% do not specify the value of SameSite. Nearly 100% of third-party cookies set the SameSite attribute to None, in order for these cookies to be sent in a cross-site context.SameSite attribute for cookies on desktop client.

SameSite attribute and its value for both first-party and third-party cookies on mobile clients. We see very similar results as for desktop clients. 3% of first-party cookies set the SameSite attribute to Strict, 19% use SameSite=Lax (which is the default on Chrome), 11% set the value to None and 63% do not specify the value of SameSite. Nearly 100% of third-party cookies set the SameSite attribute to None, in order for these cookies to be sent in a cross-site context.SameSite attribute for cookies on mobile client.

The overall distribution of this attribute for first- and third-party cookies across clients is similar to last year’s: nearly 100% of third-party cookies are sent on cross-site requests (SameSite=None) which can enable cross-site tracking.

A majority of first-party cookies (66% on desktop, 62% on mobile) do not set this attribute and so are assigned by Chrome the default Lax behavior that 19% other first-party cookies explicitly pick, leaving only 3% setting it to the Strict setting, and the remaining 11% being sent on both same-site and cross-site requests (SameSite=None).

Cookie prefixes

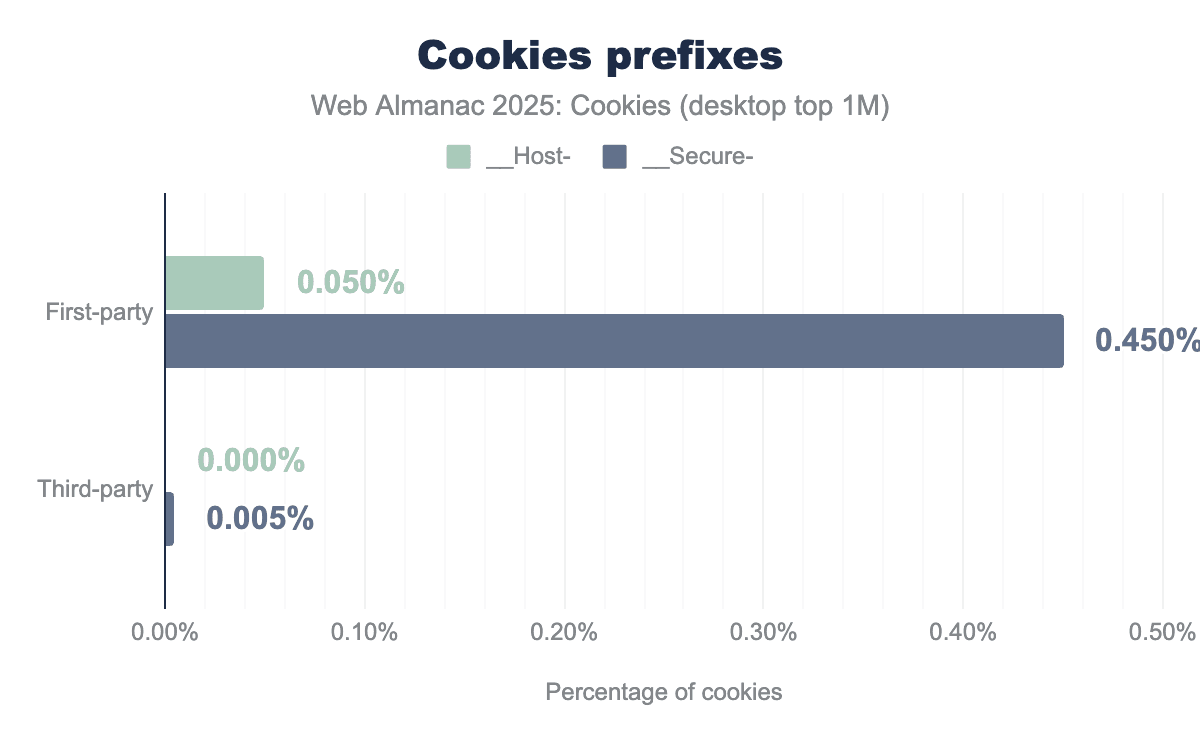

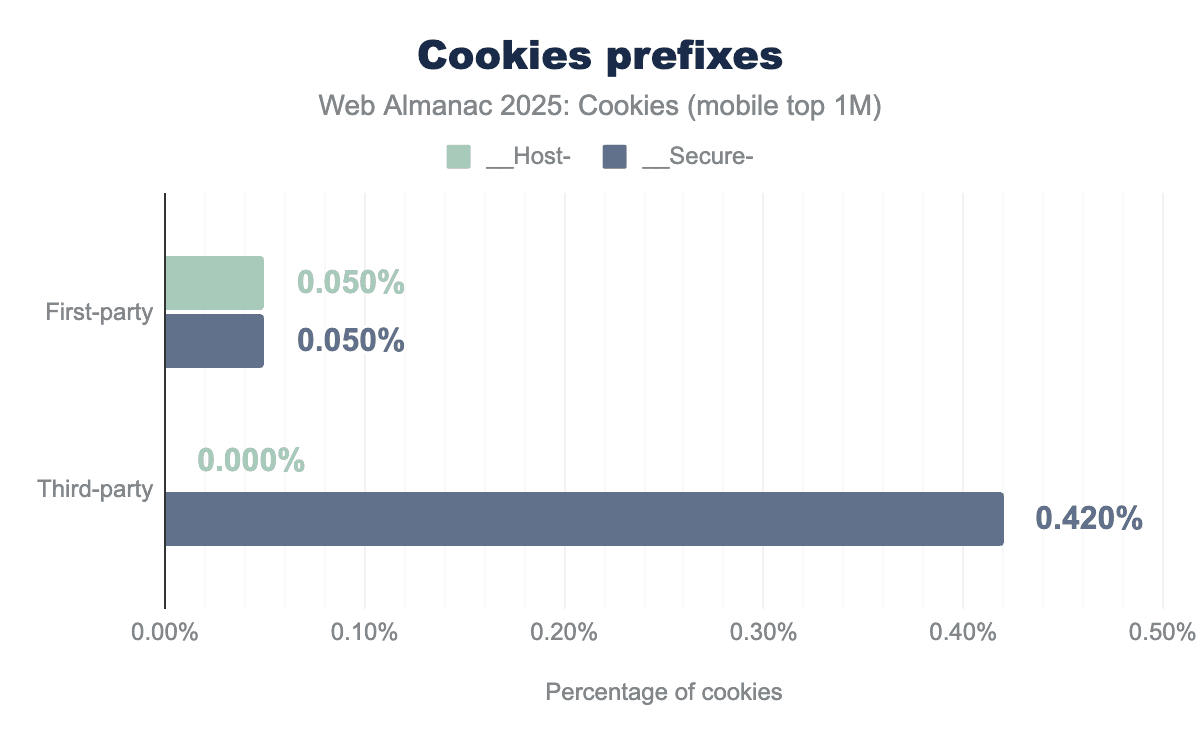

__Host- or __Secure- prefix.__Host- or __Secure- prefix.Cookie prefixes __Host- and __Secure- can be used in the cookie name to indicate that they can only be set or modified by a secure HTTPS origin. This is to defend against session fixation attacks.

Cookies with both prefixes must be set by a secure HTTPS origin and have the Secure attribute set. Additionally, __Host- cookies must not contain a Domain attribute and have their Path set to /, thus __Host- cookies are only sent back to the exact host they were set on, and so not to any parent domain.

Here, we draw the same conclusion as last year: these prefixes have seen very low adoption on the web since their introduction 10 years ago, and so, in practice the defense-in-depth measure that they provide remains unused.

Top cookies and domains setting them

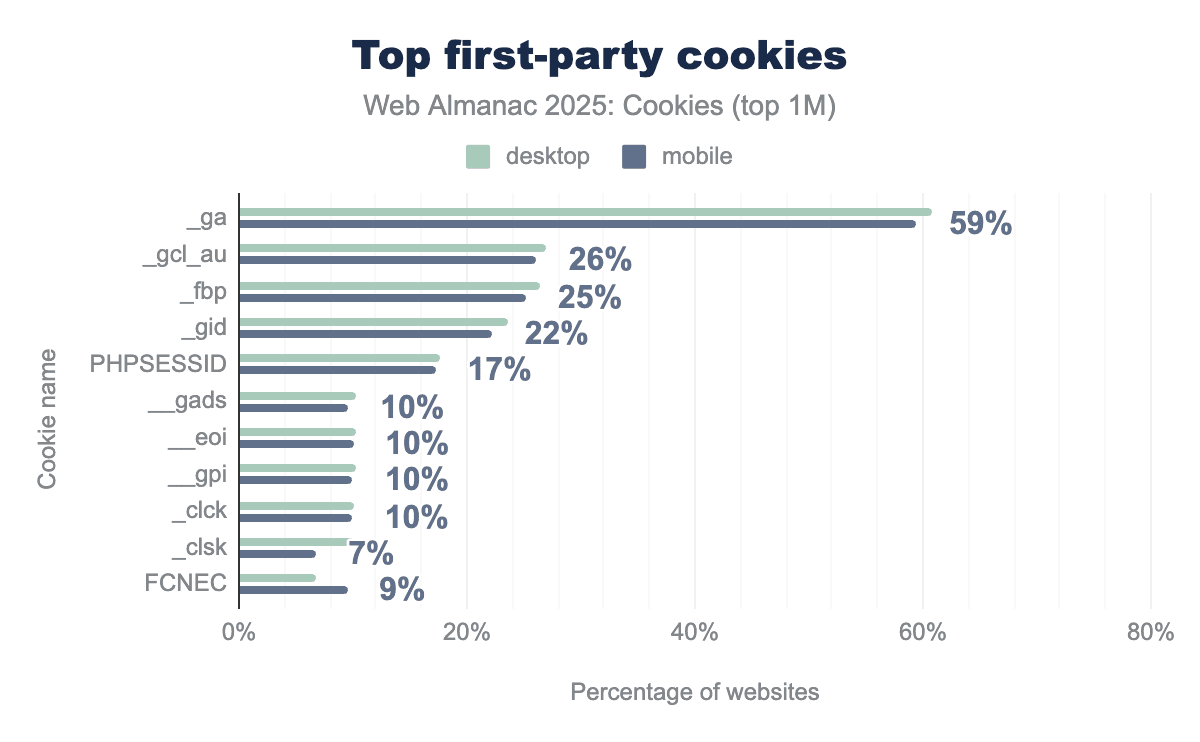

_ga and _gcl_au cookies, which are used for website statistics, analytics reports, and targeted advertising, on around 60% and 25% of websites, respectively, for both mobile and desktop clients.The previous chart reports the top 10 most common first-party cookies names being set. Google Analytics sets the _ga and _gcl_au cookies, which are used for website statistics, analytics reports, and targeted advertising, on around 60% and 25% of websites. Other cookies present in this top 10 are related to online tracking, session cookies used to identify user’s sessions, or performance.

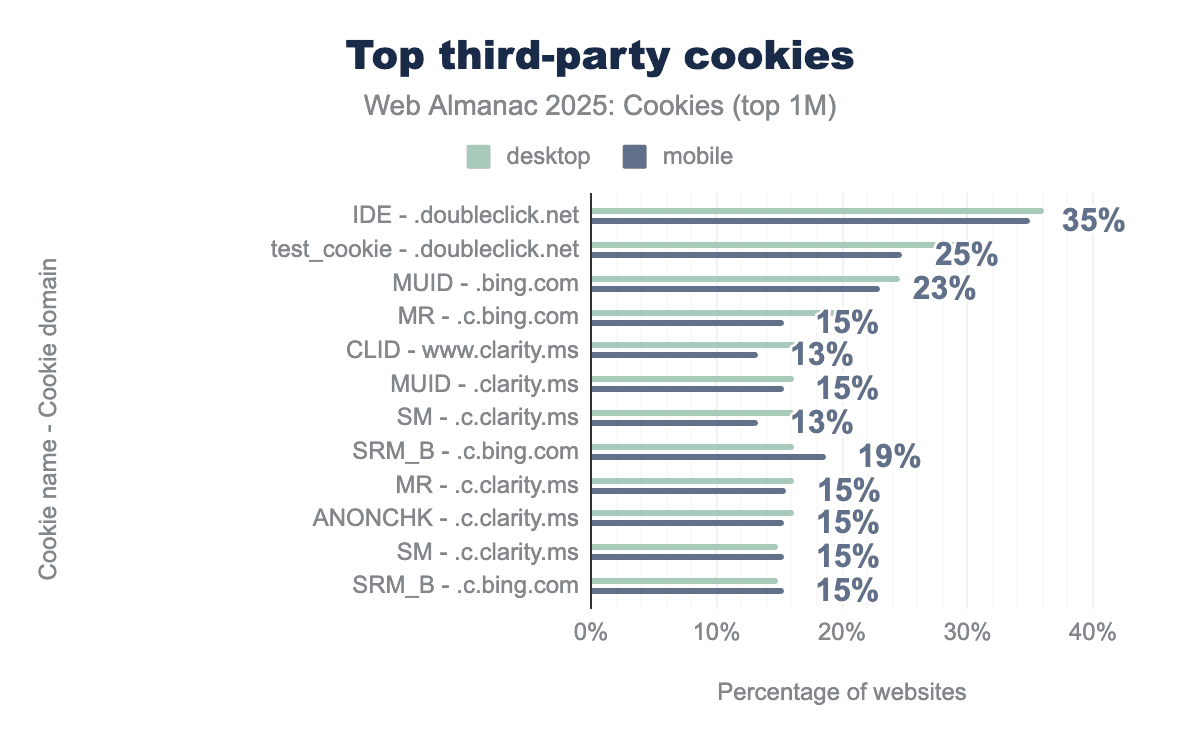

Similarly, this figure shows the top 10 most common third-party cookies being created on the top million websites.

The IDE and test_cookie cookies are set by doubleclick.net (owned by Google) and are present on more than 35% and 25% of websites respectively. DoubleClick checks if a user’s web browser supports third-party cookies by trying to set test_cookie.

MUID from Microsoft comes next, present on more than 23% of websites, and is also used for targeted advertising and cross-site tracking.

As already pointed out in the Partitioned cookies section, this year we do not observe the YSC and VISITOR_INFO1_LIVE from YouTube among top third-party cookies anymore. This is likely due to changes from YouTube (perhaps linked to Google’s announcements such as this one on the Privacy Sandbox proposals), since the 2024 analysis. It appears that these cookies are not set anymore when the embedding page is just loaded and the video has not been played. Additionally, Google’s Privacy & Terms also document that VISITOR_INFO1_LIVE is being replaced by a __Secure-YNID cookie.

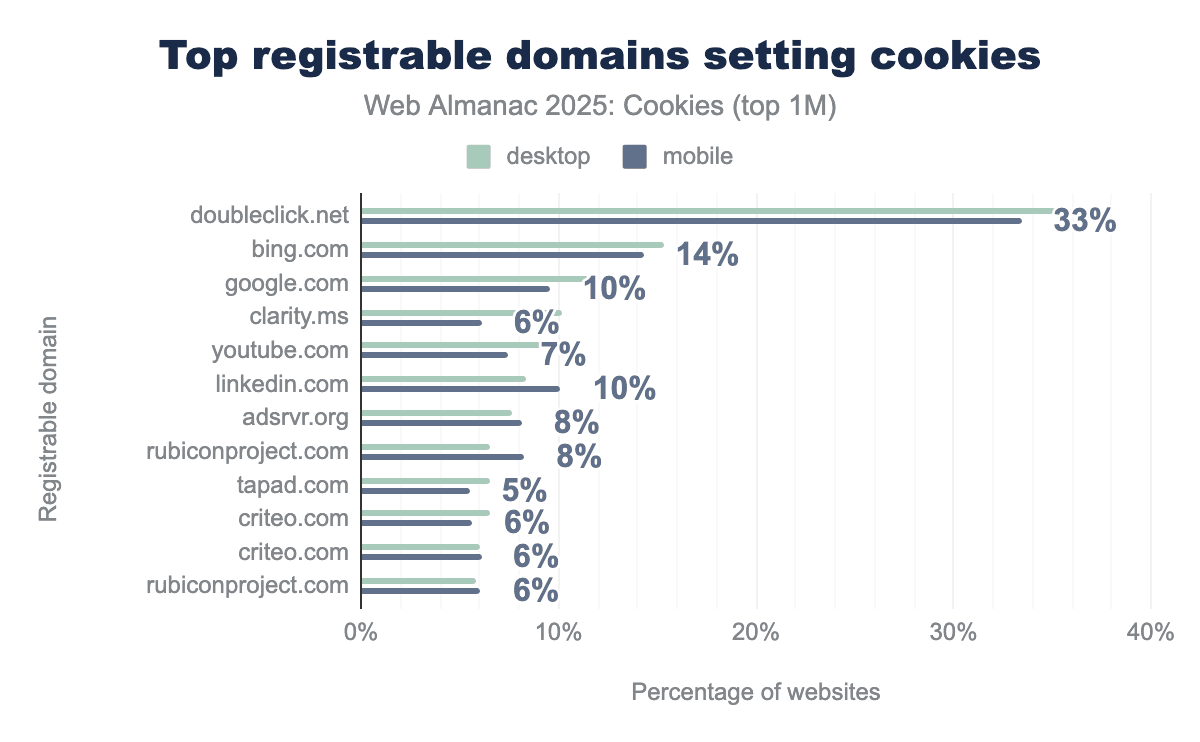

Perhaps, unsurprisingly from prior results, the 10 most common domains that set cookies on the web are all involved with search, targeting, and advertising services.

Google’s coverage (doubleclick.net, google.com, and youtube.com) is reaching at least 33% of the websites, and Microsoft’s (bing.com, clarity.ms, linkedin.com) at least 14%.

Number of cookies set by websites

| Percentile | First-party | Third-party | All |

|---|---|---|---|

| min | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| p25 | 3 | 2 | 4 |

| median | 7 | 7 | 9 |

| p75 | 13 | 16 | 23 |

| p90 | 22 | 40 | 44 |

| p99 | 45 | 399 | 395 |

| max | 178 | 885 | 915 |

| Percentile | First-party | Third-party | All |

|---|---|---|---|

| min | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| p25 | 3 | 2 | 4 |

| median | 6 | 4 | 9 |

| p75 | 12 | 15 | 22 |

| p90 | 21 | 39 | 43 |

| p99 | 45 | 400 | 396 |

| max | 178 | 801 | 831 |

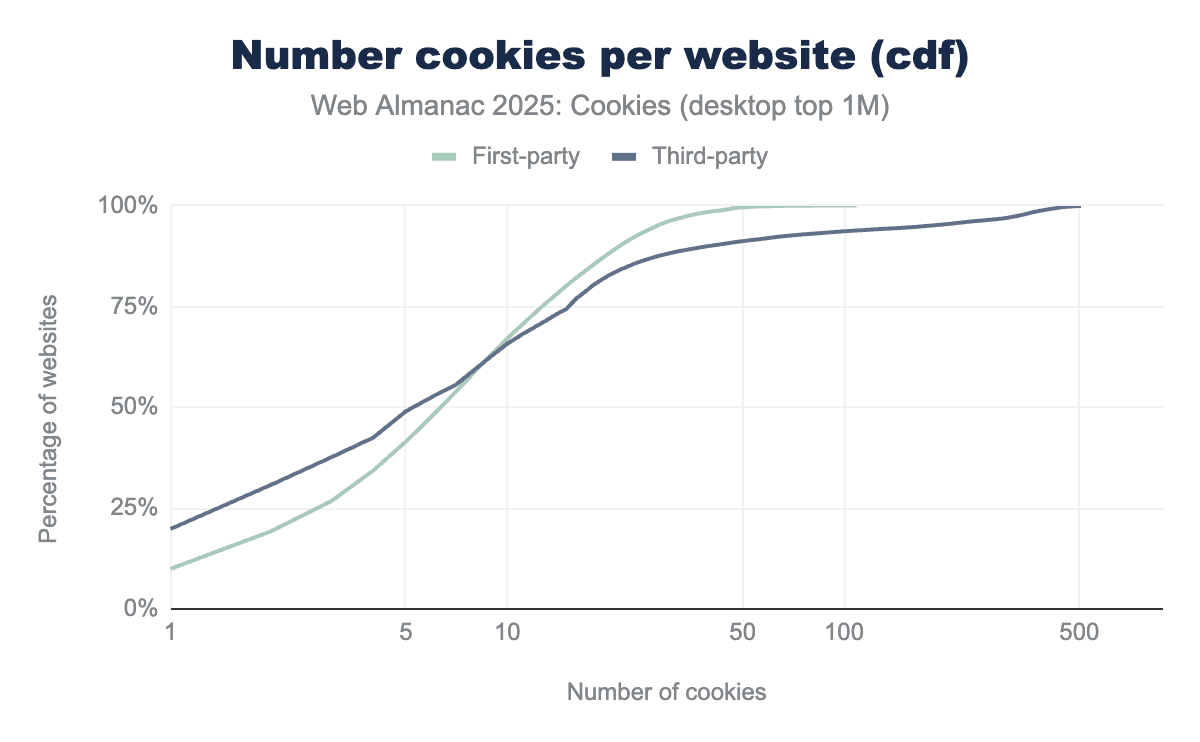

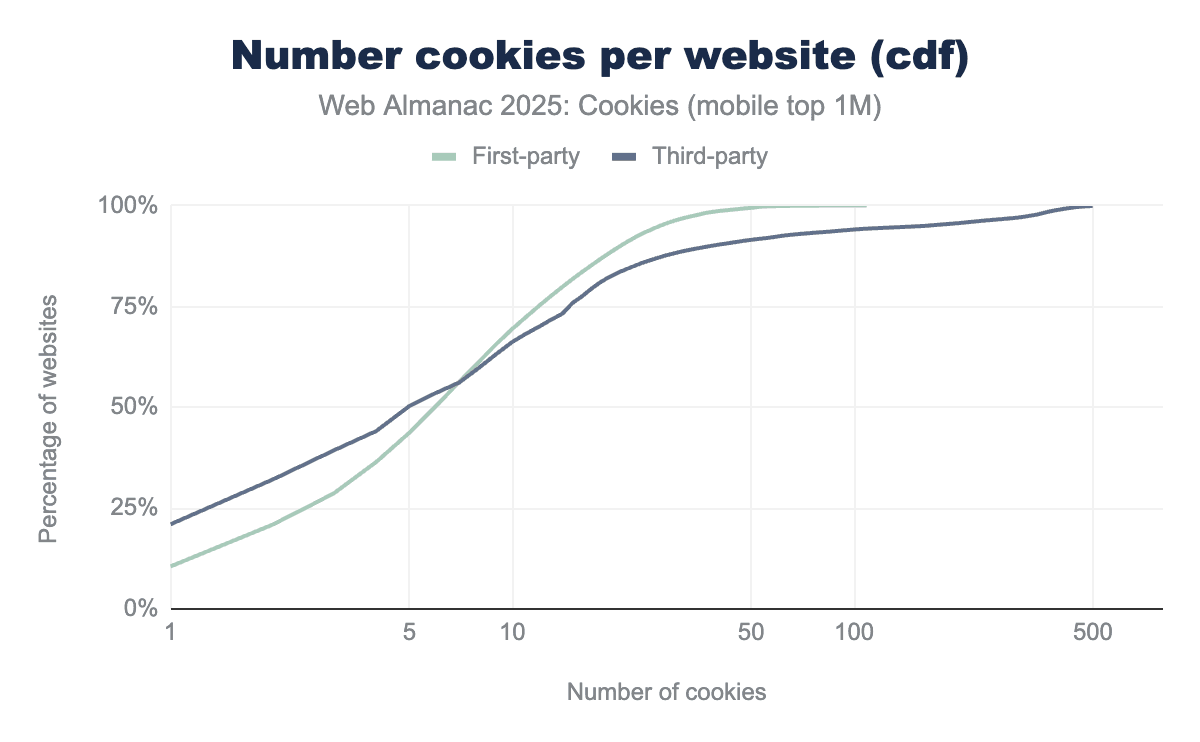

Websites set a median of 9 cookies overall, with 7 first-party and 7 third-party cookies on desktop, and 6 first-party and 4 third-party cookies on mobile.

The tables report several other statistics about the number of cookies observed per website and the figures below display their cumulative distribution functions (cdf). For example: on desktop a maximum of 178 first-party and 885 third-party cookies are set per website:

Size of cookies

| Percentile | First-party | Third-party | All |

|---|---|---|---|

| min | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| p25 | 29 | 22 | 24 |

| median | 41 | 39 | 40 |

| p75 | 67 | 59 | 64 |

| p90 | 157 | 145 | 149 |

| p99 | 414 | 321 | 338 |

| max | 4090 | 4096 | 4096 |

| Percentile | First-party | Third-party | All |

|---|---|---|---|

| min | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| p25 | 22 | 29 | 24 |

| median | 39 | 41 | 40 |

| p75 | 62 | 67 | 65 |

| p90 | 145 | 162 | 150 |

| p99 | 326 | 414 | 388 |

| max | 4096 | 4081 | 4096 |

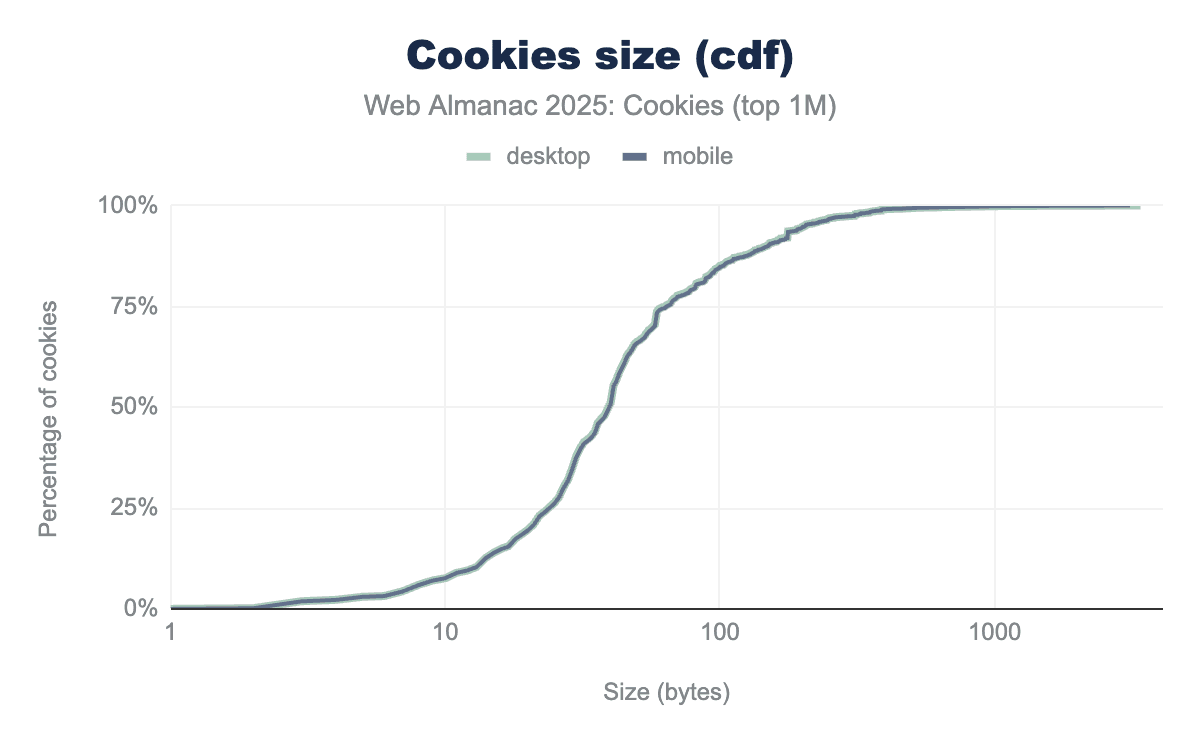

We find that the median size of cookies across all observed cookies is 40 bytes and with a maximum of 4 KB which is consistent with the limits defined in RFC 6265.

Similar to last year, we observe some cookies that are of a single byte in size, these are likely set by error by empty Set-Cookie headers.

We can chart the cumulative distribution function (cdf) of the size of all the cookies seen on the top 1M websites for each client:

Persistence (expiration)

| Percentile | First-party | Third-party | All |

|---|---|---|---|

| min | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| p25 | 1 | 30 | 21 |

| median | 365 | 360 | 364 |

| p75 | 395 | 365 | 390 |

| p90 | 400 | 400 | 400 |

| p99 | 400 | 400 | 400 |

| max | 400 | 400 | 400 |

| Percentile | First-party | Third-party | All |

|---|---|---|---|

| min | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| p25 | 1 | 30 | 30 |

| median | 365 | 270 | 360 |

| p75 | 395 | 365 | 390 |

| p90 | 400 | 400 | 400 |

| p99 | 400 | 400 | 400 |

| max | 400 | 400 | 400 |

Cookies are set to an expiration date when they are created. If session cookies expire immediately after the session is over (see previous section), most first- and third-party cookies do not and have a median age of a full year.

The longer cookies live, the longer they can be used for re-identification or cross-site tracking which is why most tracking cookies are typically set to be stored in the browser for a longer time.

The maximum age among the cookies that we can observe with the instrumentation and collection of the HTTP Archive Tools for this chapter is of 400 days, due to the hard limits that Chrome imposes on cookie Expires and Max-Age attribute.

Conclusion

The observations from this chapter confirm the conclusions from last year’s analysis:

- A majority (60%) of cookies encountered on the web are third-party cookies and popular websites have significantly more third-party cookies than less popular sites.

- Most popular cookies can be linked to advertising, tracking, and analytics use cases.

- Cookies tend to be long-lived with a median average lifetime of 12 months. Ephemeral session cookies only represent 19% of first- and 7% of third-party cookies.

- Other restrictions on cookies capabilities are used very little to not at all: if 10% of third-party cookies are partitioned (which represents a slight uptake from last year’s 6%), 100% of third-party cookies have

SameSite=Noneallowing them to be sent in cross-site requests. Additionally, cookies prefixes adoption is almost non-existent.

Finally, while several web browsers have deprecated or limited third-party cookies due to privacy concerns, Google has decided to still support them in Chrome. Google is also phasing out most technologies from its Privacy Sandbox initiative, initially designed to “create a thriving web ecosystem that is respectful of users and private by default”. As a result, whether trackers use third-party cookies or develop other techniques (first-party syncing, fingerprinting, etc.) to track users online, cookies remain a fundamental component of the web that continue to pose privacy and security risks for users.