PWA

Introduction

The year 2015 was the first time we read about Progressive Web Applications. Nine attributes—responsive, connectivity independent, app-like-interactions, fresh, safe, discoverable, re-engageable, installable and linkable—were what defined the cutting edge of what could be achieved with web technologies back then. The PWA concept was coined 10 years ago, and it is with great pride that we look at the state of this set of technologies, one decade after its ideation.

The concept of a PWA has evolved a lot in these 10 years, and different browsers support it in different variations and with different names. An idea that started as a way of enabling access to a web application via “Add to home screen” on mobile browsers is now present on multiple platforms and devices. This set of technologies allow to integrate web content directly into the underlying platform, enabling at the same time advanced capabilities and a more native look and feel. Let’s dive into what the last couple of years have brought to PWAs.

Changes to PWA/web apps

The last couple of years have seen new features coming to web apps that enable more customization, advanced control of the application’s behavior and better performance. But above all, there has been progress in supporting web apps (to an extent or another) on multiple engines!

Chromium based browsers prompt for an application installation once a minimum set of requirements is identified. This used to be the case on apps that had a manifest file, a service worker and were served over a secure connection. For a while this was the “trifecta” for PWA installability. This has changed and nowadays only the manifest is required (the HTTPS connection is still there, do not worry); service workers are no longer required for browsers like Edge and Chrome to display the installation prompt.

On the other hand, Safari does not prompt for web app installation. It does however allow any web page to be installed as an application by adding it to the dock on macOS 14.

Another great news for PWAs is that Firefox now supports web apps from version 143! It is available for PWAs on Windows only, following what has been a “top request from the Mozilla Connect community”.

With web apps, being web-based, one of the concerns of not having a service worker is offline support. It is true using service workers allow developers to provide a great offline experience by caching resources that make up the UI of the web app. The change in requirements (for Chromium) or default behaviors (for Safari and Firefox) means that the browser may create a default offline experience that shields users from lack of connectivity.

With this summary, we are now ready to jump into the data and understand the state of PWAs right now. Where possible we will also by comparing this year’s data with the data from 3 years ago—which was the last time there was a chapter on PWAs.

Service worker

Service workers remain essential to allow advanced capabilities like background sync, offline support and push notifications to web apps. This year, the data suggest around one fifth of web properties are using service workers.

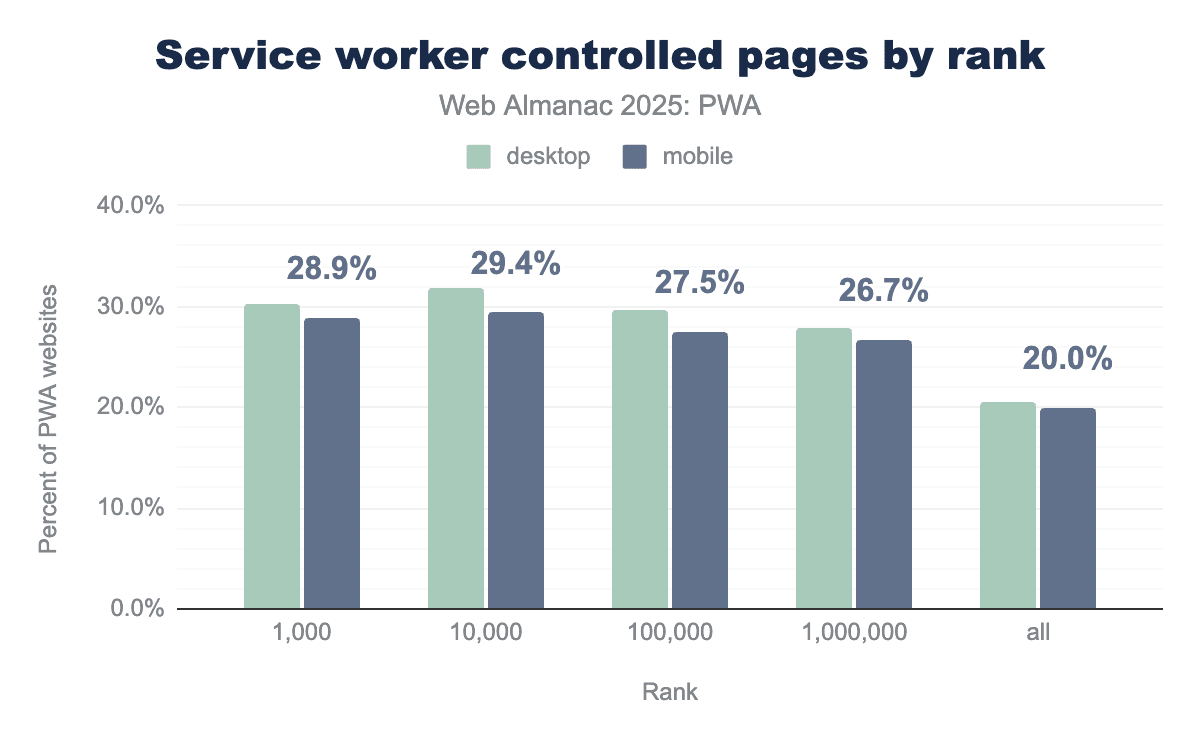

To start strong, we will look at the service worker controlled pages by rank. From the top 1,000 pages, 30.3% (desktop) and 28.9% (mobile) are managed by a service worker. This is around a 20% increase compared to the data from 3 years ago.

Overall, across every rank grouping there was a strong increase, when looking at all the percentage of PWA websites going from 1.4% (desktop and mobile) in 2022 to 20.5% (desktop) and 20.0% in mobile.

Following we have usage data for capabilities of service worker by events, methods and objects.

Service worker events

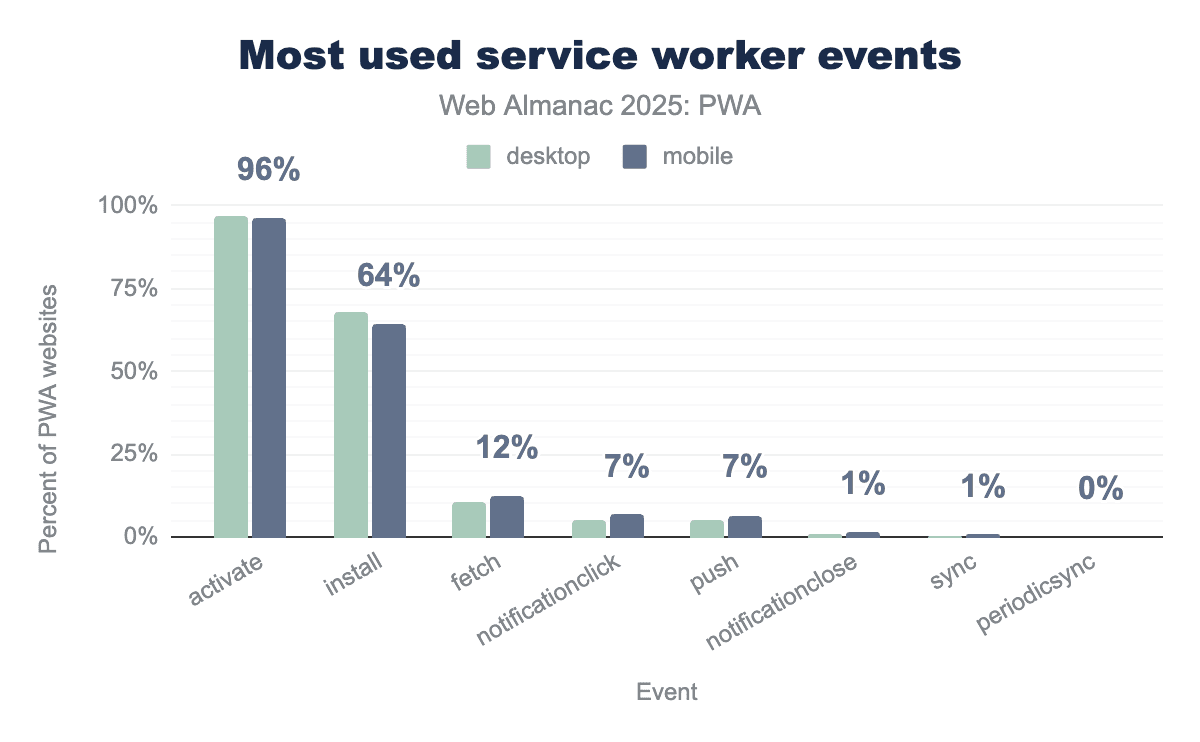

activate event appearing on 96% of PWA sites and the install event used by 64%. Functional events see lower but notable adoption, with fetch at 12% for intercepting network requests and push and notificationclick both at 7%.The most used event for these service workers is the activation (activate) with almost every service worker using it, around 96% of PWAs using it. The install event takes second place with around 64% usage. Both install and activate are core lifecycle events so these numbers do not come as a surprise. This might suggest that applications are caching resources to speed up their loading times and performing service worker management.

Usage of other advanced events, like fetch, notificationclick and push falls considerably, possibly due to these being capabilities that fall into more advanced scenarios, like intercepting network requests, bypassing the default offline UX or delivering notifications from a push service.

Service worker methods

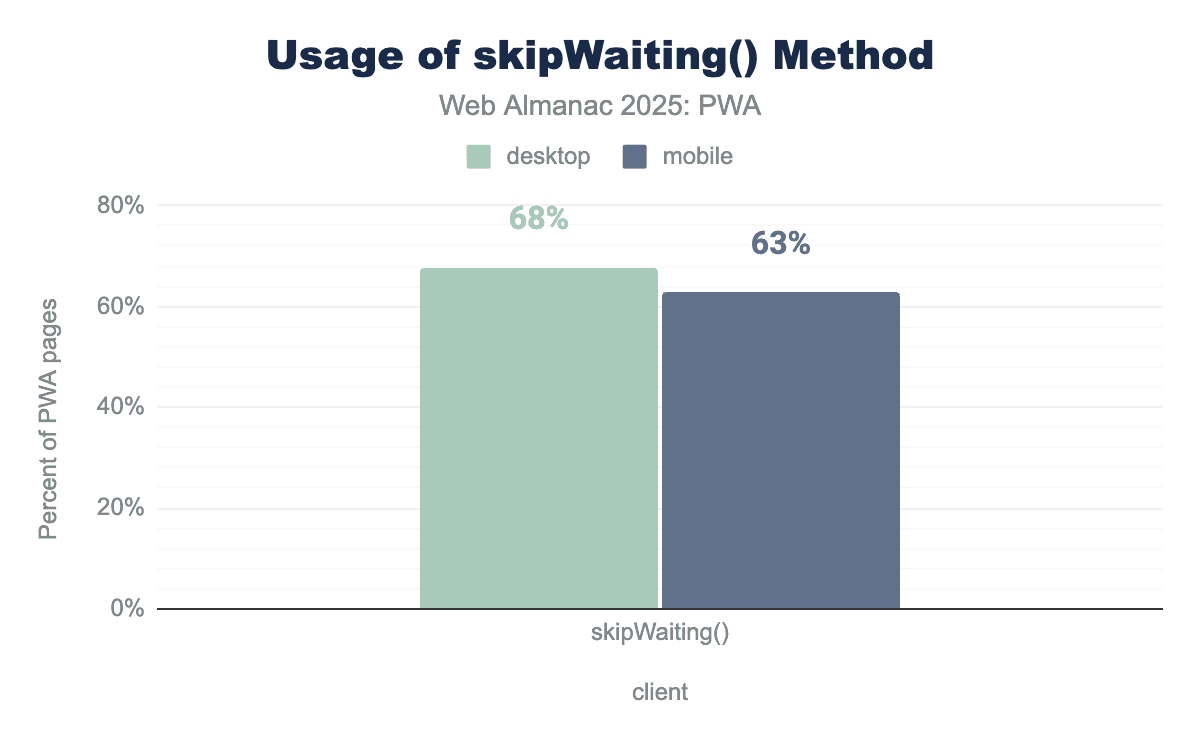

skipWaiting being used on approximately 68% of desktop PWA pages and 63% of mobile PWA pages.Looking at the most used service worker method, skipWaiting() has a notable use, with 68% usage on desktop and 63% on mobile. The browser will activate the service worker and replace the old one immediately. This implies developers are keen to ensure users don’t get stuck with stale assets. This is beneficial for applications that require frequent updates, like dashboards and messaging apps. It basically helps users get the latest version of the application right away.

Service worker objects

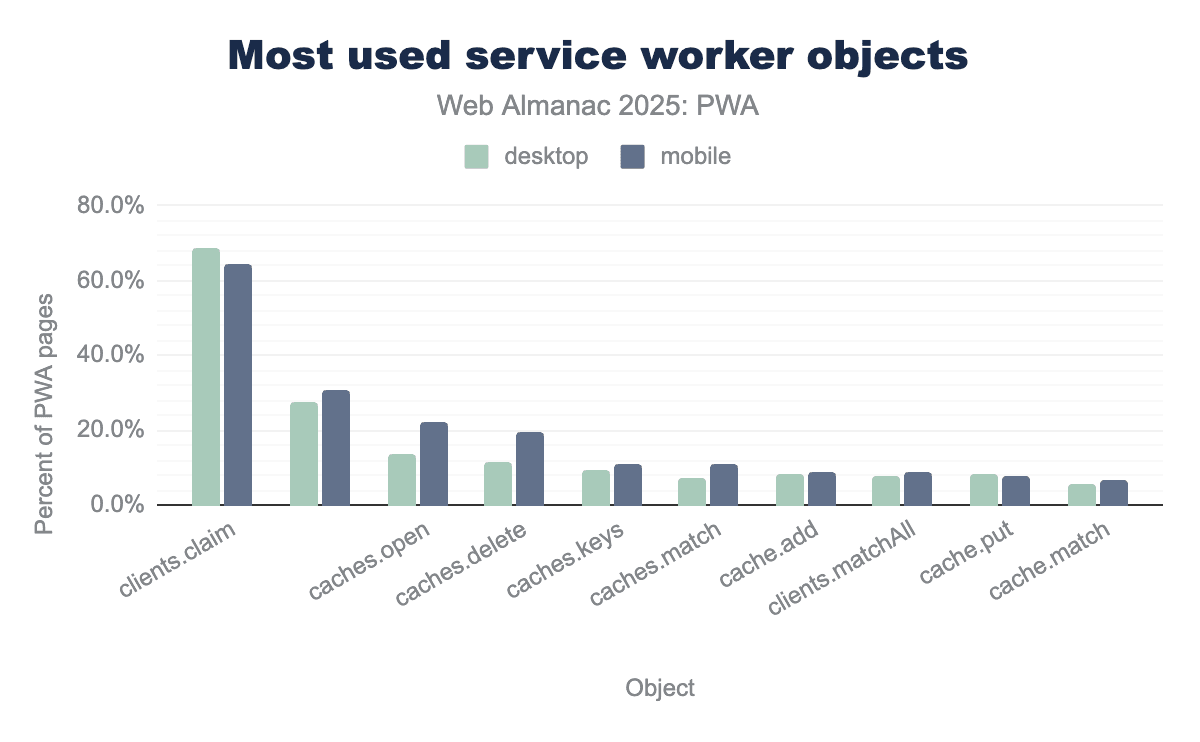

clients.claim is the most widely used object, appearing on approximately 67 percent of desktop PWA pages and 63 percent of mobile PWA pages. Other common objects include caches.open and caches.delete, which are notably more prevalent on mobile devices than on desktop.The most used service worker objects are clients, caches and cache. For clients, this can be expected as it is the way to tell the service worker to take control of all open pages by calling clients.claim(). Regarding caches, management methods appear on top, also not surprising considering that these are the methods that developers would use to make sure their assets are up to date to achieve that speedy page load.

As hinted before, the main methods from these correspond to claim, open/delete/keys/match, and add.

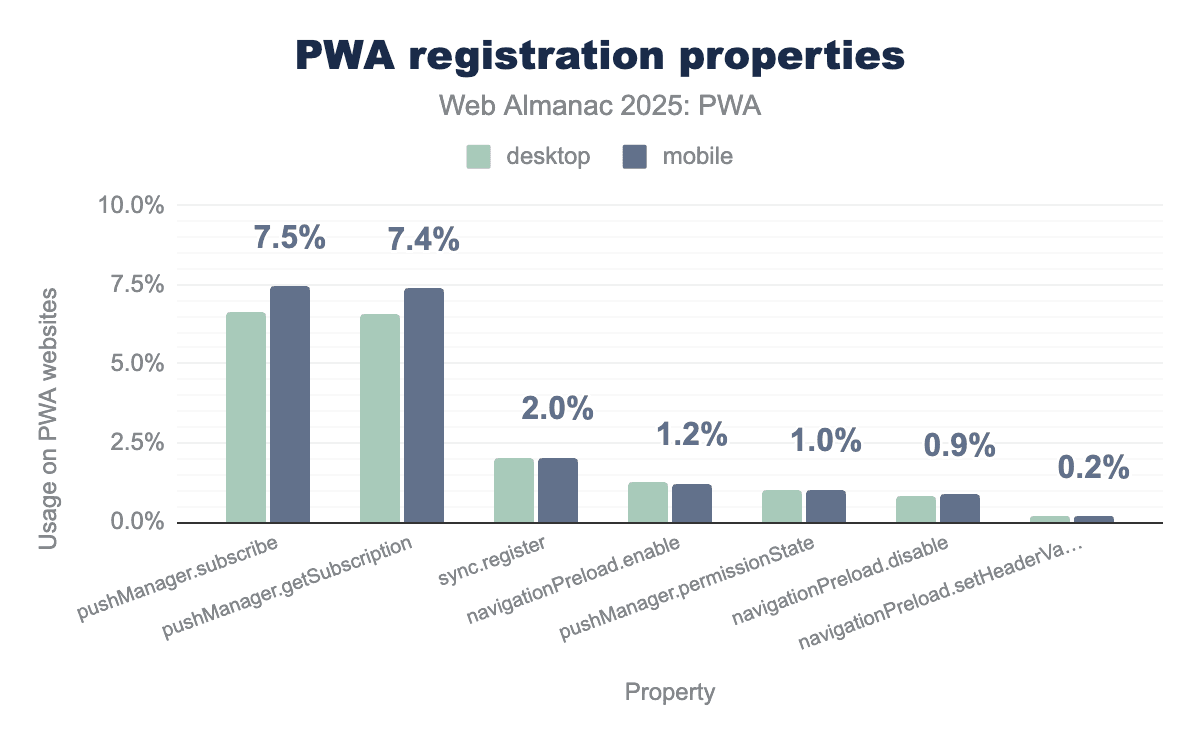

Registration properties

pushManager.subscribe and pushManager.getSubscription are the most utilized properties, each appearing on approximately 7% of PWA websites across both platforms. In contrast, advanced synchronization and performance properties like sync.register and navigationPreload.enable see much lower implementation, with usage rates hovering between 1% and 2%. Overall, the visualization demonstrates that push notification capabilities are significantly more common in the PWA ecosystem than background sync or navigation preloading features.Diving deeper into service worker functionality, the data sheds some light into advanced capabilities that PWAs are using. For all PWAs using service workers across desktop and mobile, ~7% are registering for pushManager, 2% register for sync and 2% register for navigationPreload.

Web application manifest

The web application manifest is now, more than ever, the most important part of a web app. It defines a look and feel, enables advanced capabilities that are gated behind an installation and is becoming an integral part that identifies a web application as a whole. But in order to be effective, the manifest file needs to be well formed.

For the current year, 94.5% of desktop sites and 94.9% of mobile sites are parseable. There is no change from the last data set, and same as last time around, the fact that the manifest file was able to be parsed does not imply completeness or minimum availability of features. Many values in the manifest, as important as they may seem, have reasonable fallbacks in place.

From those parseable manifests, we will now look at individual present fields. This can give us an understanding of how developers are using the manifest file and if there have been changes since 2022.

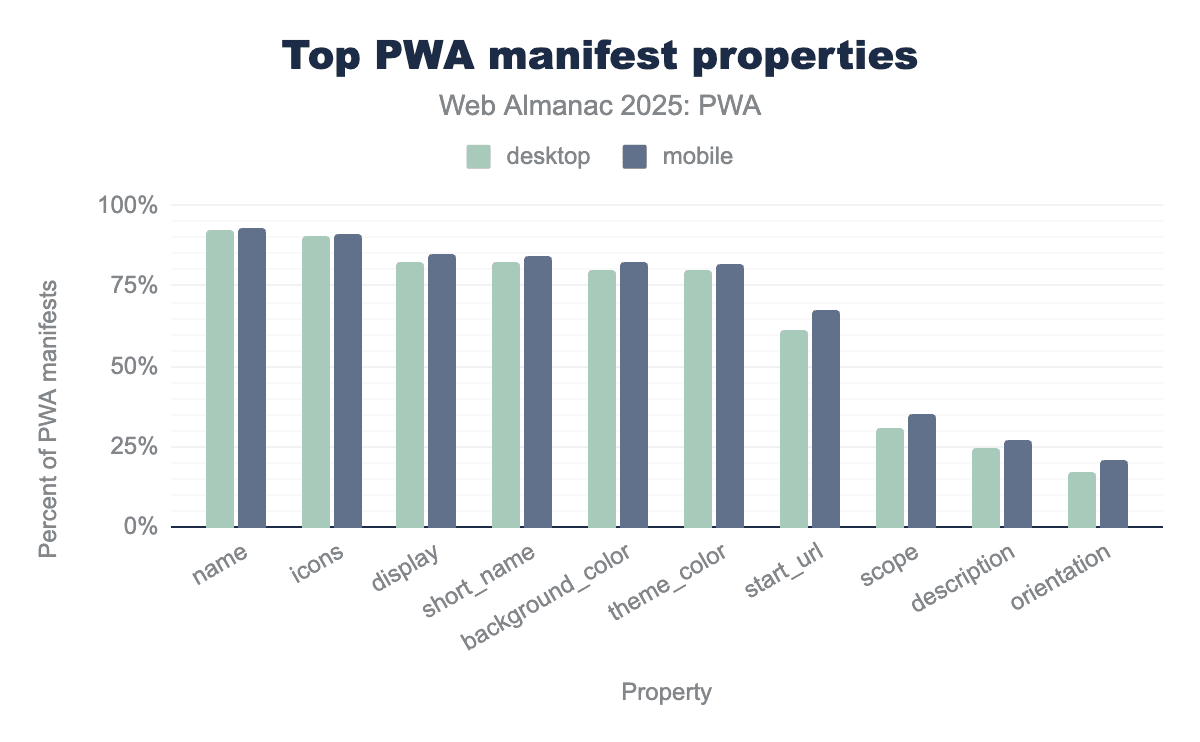

Manifest properties

name and icons appearing in over 90% of manifests, followed closely by short_name, display, and theme_color at roughly 80%. Mobile PWAs exhibit slightly higher adoption across every listed property compared to desktop, particularly for functional fields like start_url and scope. Overall, the data illustrates a high level of standardization for basic PWA identification, while more descriptive or restrictive properties like description and orientation remain significantly less common.Straight up, these are the most used PWA manifest properties: name, icons, short_name, display and background_color. The top 4 most used properties are the same ones from 2022, with subtle notable changes regarding their order.

Let’s examine how individual members rate in the totality of manifest files scanned by the Web Almanac. Unless noted otherwise, values are very similar so I will refer to both mobile and desktop sites.

| Manifest field | Desktop | Mobile |

|---|---|---|

name |

92% | 93% |

icons |

90% | 91% |

short_name |

82% | 85% |

display |

82% | 85% |

background_color |

80% | 82% |

theme_color |

80% | 82% |

start_url |

61% | 68% |

scope |

31% | 35% |

description |

25% | 27% |

orientation |

17% | 21% |

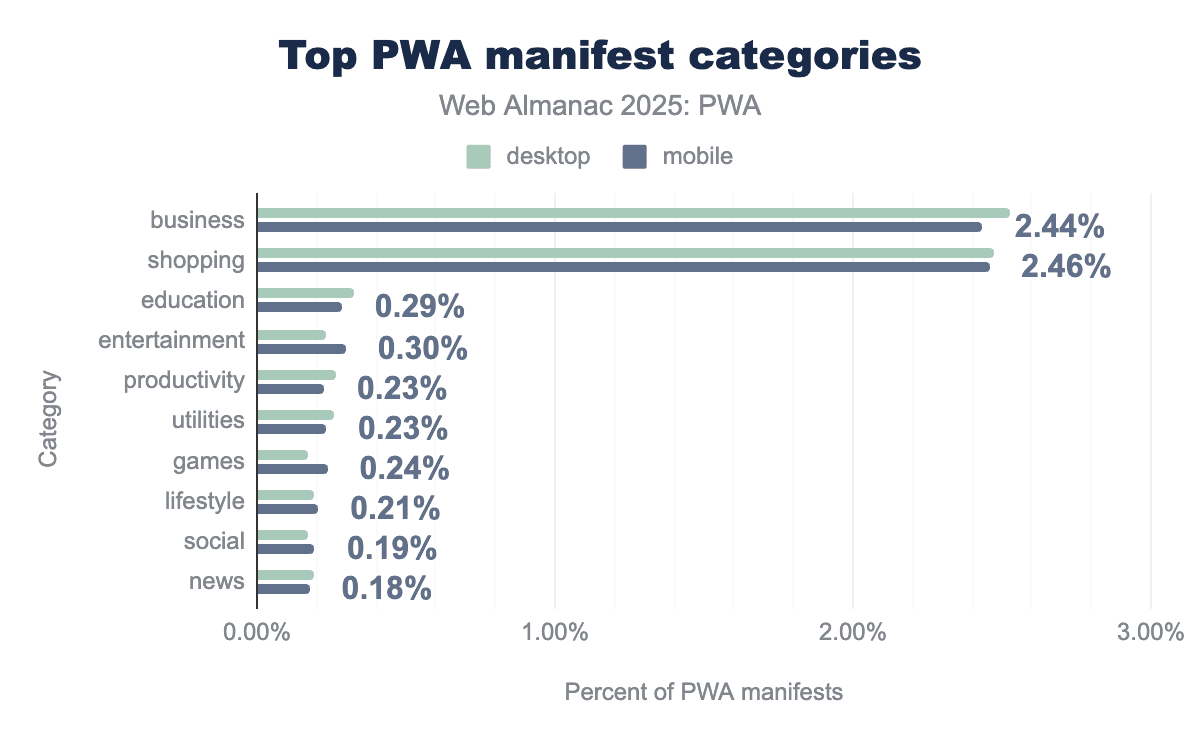

For the manifests that specify the categories member, the top categories are:

shopping and business are the overwhelmingly dominant categories, each represented in approximately 2.4% to 2.5% of manifests across both client types. In contrast, all other listed categories—including education, entertainment, games, and productivity—see significantly lower adoption, with each appearing in less than 0.3% of manifests.

While the manifest key categories is not used in many PWAs, these results hint at the top verticals on which web apps are more popular.

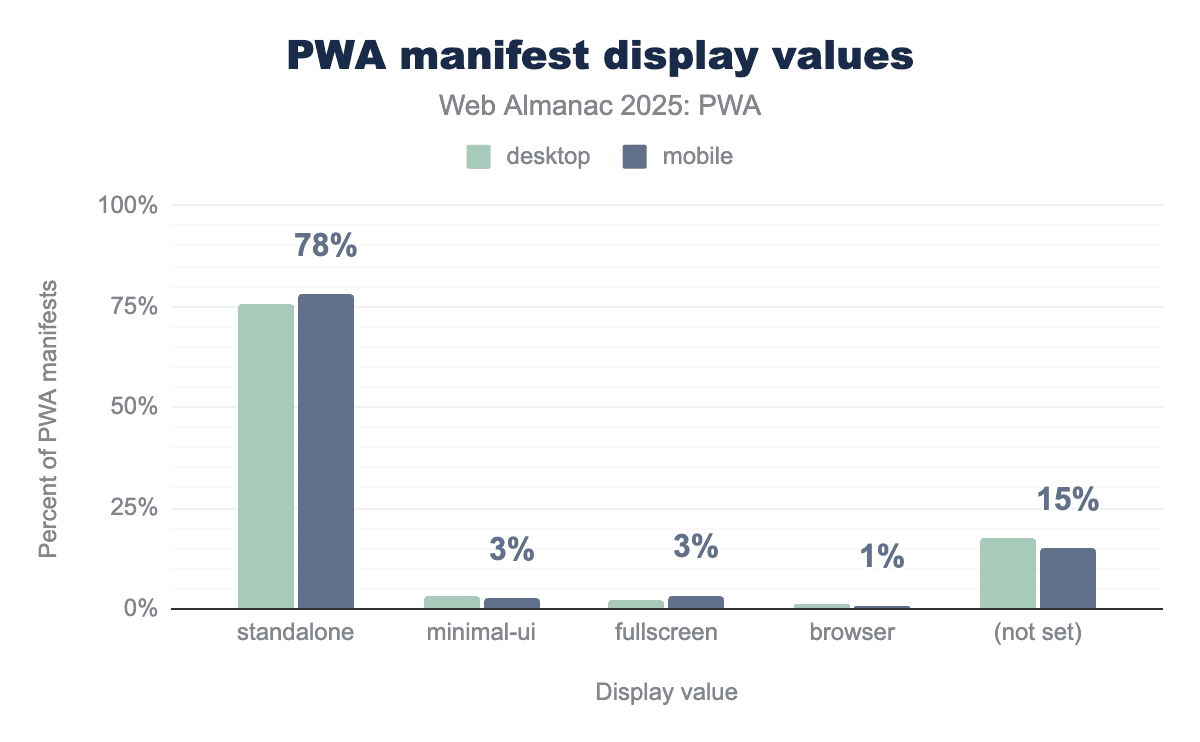

Manifest display values

The display member is used to specify the preferred display mode for the web app. Different browsers have different interpretations of these values, but overall it hints to the UA how much of the browser UX to show/hide.

standalone value is the overwhelmingly dominant choice, utilized by 78% of mobile PWA manifests and a similarly high percentage on desktop to provide an app-like experience. Other standardized display values, such as minimal-ui, fullscreen, and browser, see very low adoption, with each accounting for 3% or less of the total. Additionally, a notable portion of manifests, roughly 15%, do not have a display value set.

Most web apps (78%) opt for a standalone value for the display member. From the documentation, standalone “opens the app to look and feel like a standalone native app”. This is not surprising as the general intention of a web app for a developer would be to have the app look more native-like, removing the browser chrome and some other UX. On the end this is something that varies with the implementation, as for example in Chromium browsers you get a ... menu and on Firefox some browser UI like the URL bar still remains for installed apps.

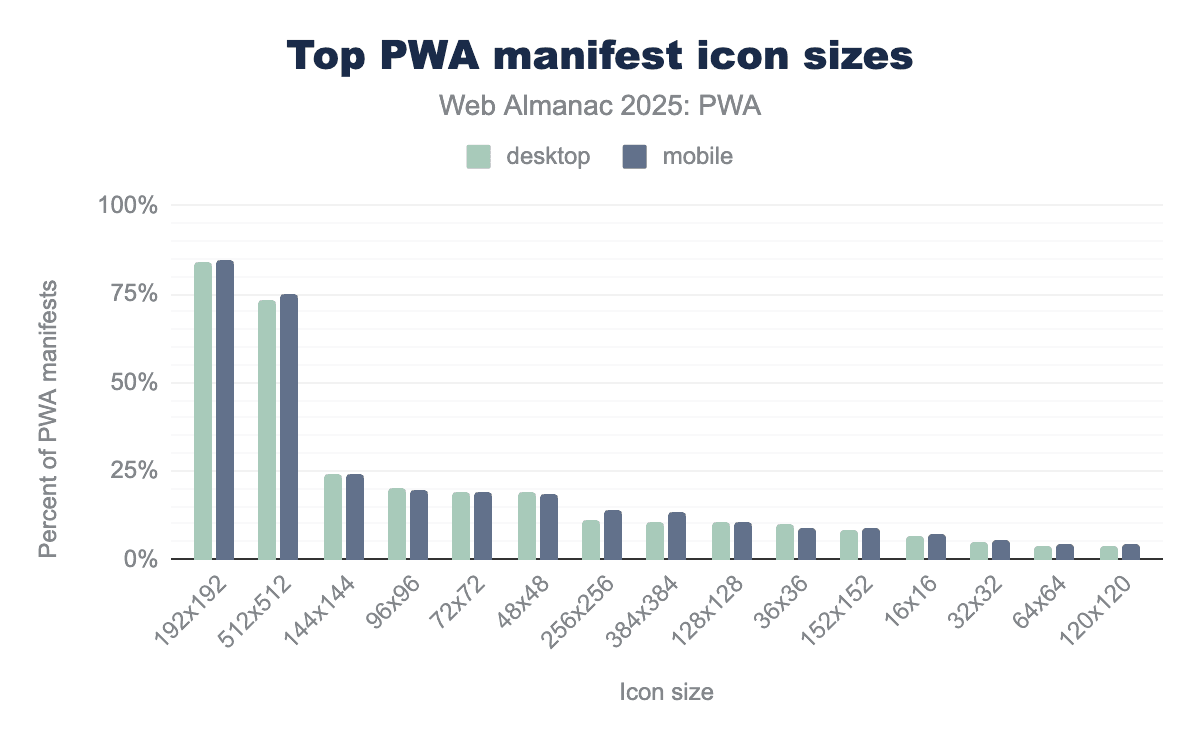

Manifest icons sizes values

Top sizes include 192x192 and 512x512.

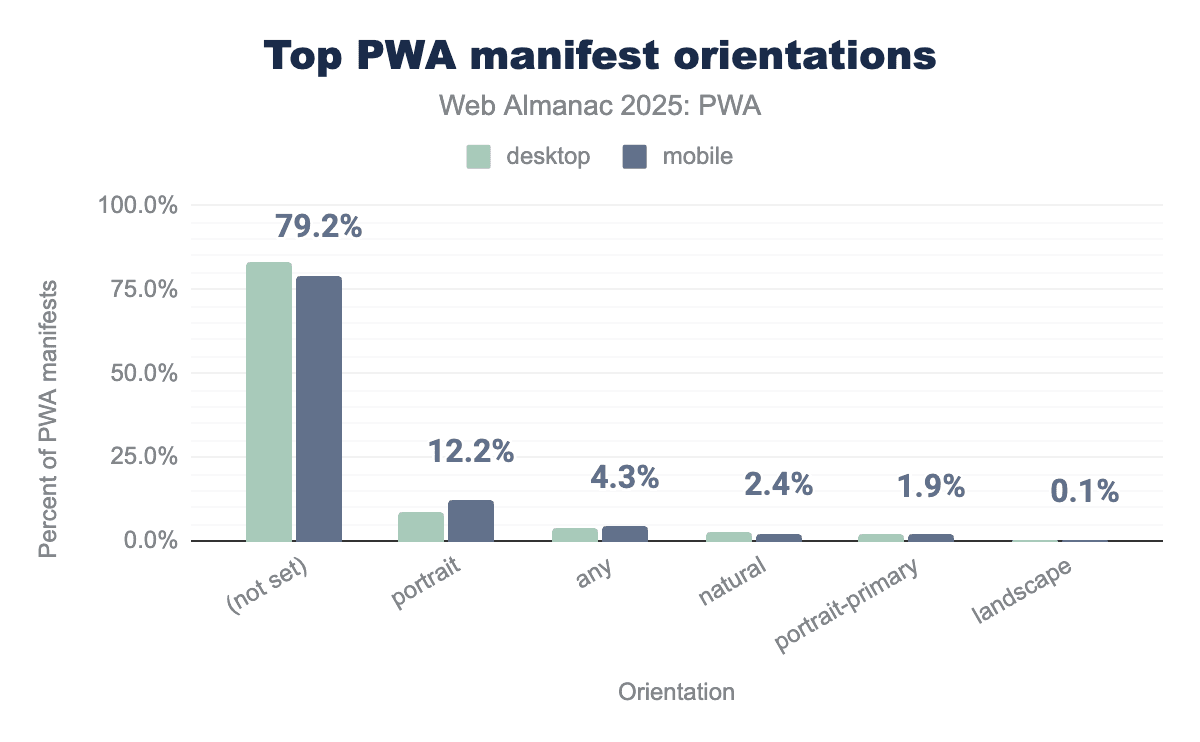

Manifest orientation values

portrait is the most common selection at approximately 12 percent, with mobile applications showing a significantly higher tendency to lock this orientation compared to desktop versions. Other specific orientation values such as any, natural, and portrait-primary see very low adoption, each appearing in fewer than 5 percent of manifests, while landscape is the least utilized at just 0.1 percent.Unsurprisingly, around 79.2% of PWAs do not set orientation. Responsive design and modern development make defining the app’s orientation less necessary, but portrait takes second place with around 12.2%.

Service worker and manifest usage

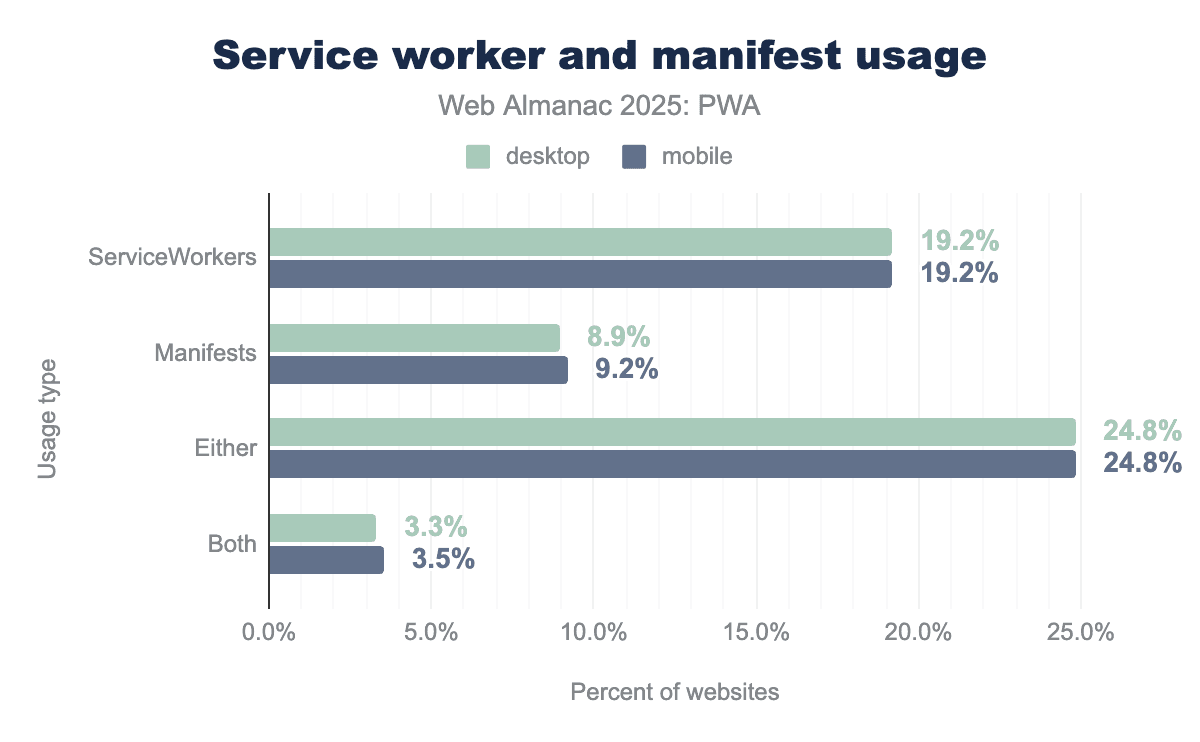

We’ve seen the latest data on what the most used service worker and manifest features are. In 2025, we can see that roughly one fifth of sites use service workers, and roughly one tenth use manifests.

Overall, there are considerable changes to the data from the 2022 Web Almanac. Service worker usage has taken a huge leap from around 1.7% to 19.2%. That is around a 10 times increase in adoption. Manifest usage is slightly higher but remains at a very similar spot as it was 3 years ago.

Digging into this more, it looks like a lot of the growth is due to Google Tag Manager enabling service workers.

PWAs and Fugu APIs

These are the top 10 used advanced capabilities in PWAs for 2025.

| Capability | Mobile | Desktop |

|---|---|---|

| Compression Streams | 18.4% | 20.9% |

| Async Clipboard | 17.9% | 19.1% |

| Device Memory | 10.7% | 10.6% |

| Web Share | 9.6% | 9.8% |

| Media Session | 6.8% | 7.8% |

| Add to Home Screen | 6.8% | 7.3% |

| Media Capabilities | 6.3% | 7.3% |

| Cache Storage | 9.00% | 3.00% |

| Service Worker | 3.7% | 3.3% |

| Push | 1.7% | 1.6% |

There is a separate chapter dedicated to Capabilities to dive deeper in the adoption that these sort of APIs have had in 2025.

Notifications and PWAs

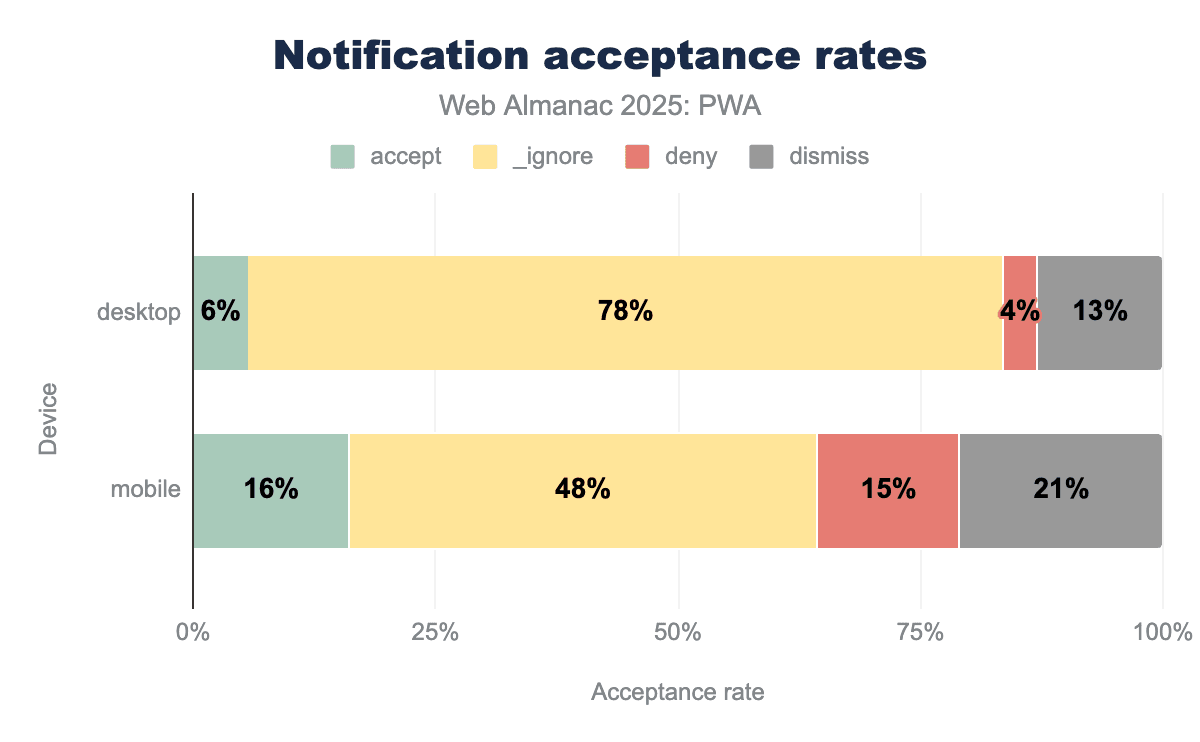

Notifications make sense for apps as they allow the user to re-engage with the application. This is a controversial capability as there is considerable bad UX and dark patterns to try to get users to accept them. The data shows that in both desktop and mobile, the most common action a user takes is to ignore these requests.

Desktop notification acceptance is overwhelmingly ignored: 78% of them are disregarded, with a slightly lower but still meaningful 48% on mobile. This is not a surprise considering overall the notification fatigue users deal with on a regular basis.

Conclusion

It has been a decade since PWAs. The landscape has changed a bit as the technology and capabilities reach maturity; we now have all major browsers (Edge, Chrome, Firefox and Safari) supporting web apps to a degree. Web apps continue to show growth and almost one fourth of web sites crawled have either a service worker or a manifest file.

If you have noticed a slow down in pace of new features, you are correct. There are less web app features being launched today than a few years ago. I believe this has to do with the fact that capability-wise the platform has reached a level of maturity that allows a wide range of use cases to be created using a web tech stack. On the other hand there is a question of adoption that is tightly coupled with cross-engine capability support. It is until (very) recently that some major browsers are starting to support (some) advanced features, yet alone the possibility to acquire or install a web app.

Whilst advanced capabilities continue to be used sparingly, likely due to slow implementor support, the oldest capabilities like Web Share are starting to show up as well, and even more niche UX features like ’window-controls-overlay’ are starting to show up in the data. Slowly but surely these features are being commoditized.

If we look back to the last Web Almanac that had a PWA chapter, these are the things we can notice:

- 2 more browsers (Safari and Firefox) have support for web apps.

- Service worker controlled pages have gone up around 20% for all PWA websites from 2022.

- There is less diversity of service worker events being used than 3 years ago. Less percentage of PWAs are using

notificationclick,push, andfetch. - Percentage of

pushManagerregistrations has dropped since 2022, likely due to the rise of usage (see note below) of service worker to focus on performance rather than pushing notifications. - Between 2022 and 2025 the total of PWA technology usage (desktop 12.5 million and mobile 15.5 million) has around doubled (desktop 5.4 million and mobile 7.9 million - 2022). The percentage of usage for service workers has surged around 10 times, and manifests have largely stayed around the same 8-9% usage.

- Ignoring notification prompts is still the most common behavior for users.

As we close the 2025 Web Almanac PWA chapter, there’s ongoing work and agreement towards looking at a way to democratize web app distribution by baking installation capabilities directly into the platform. We hope in the next 10 years the PWA technologies will follow the same fate as responsive design, where they have been commoditized and web apps that have good UX for application lifecycle management will be the norm, in conjunction with newer capabilities that redefine what a web app can do. Here’s to the next decade for web apps!