CDN

Introduction

This chapter examines the rapidly evolving landscape of Content Delivery Networks (CDNs) in 2025, with an increased focus on their role in HTTP protocol optimization. CDNs fundamentally exist to solve HTTP delivery challenges at scale, from reducing TCP connection overhead through HTTP/2 multiplexing to eliminating head-of-line blocking via HTTP/3’s QUIC transport. As HTTP protocols have evolved from HTTP/1.1’s connection limitations to HTTP/3’s advanced features, CDNs have served as the primary deployment vehicle, implementing these protocols years before origin servers adopt them.

Modern CDNs optimize delivery across the entire spectrum of web content. For highly cacheable resources (static assets, public API responses, shared content), CDNs provide traditional caching benefits enhanced by advanced compression and modern format delivery. For content with limited cacheability (user-specific data, frequently updated APIs, personalized experiences), CDNs still deliver performance improvements through connection optimization, intelligent routing, and edge processing, reducing latency even when content cannot be cached.

Building upon our comprehensive analysis from 2024, our 2025 analysis reveals shifts in protocol adoption and optimization strategies. A key focus of this chapter is the maturation of HTTP/3 adoption, the rise of modern optimization techniques like Server-Timing transparency, and the sophisticated multi-layered approaches CDNs are taking to performance, security, and user experience.

What is a CDN?

A Content Delivery Network (CDN) is a geographically distributed network of servers designed to provide high availability, enhanced performance, and improved security for web content and applications. The primary goal of a CDN is to minimize latency and optimize content delivery by serving data from locations closer to the end user.

CDNs serve as intermediary infrastructure between end users and origin servers, intercepting web requests and optimizing the complete delivery process. To understand how CDNs can enhance web performance, consider the traditional web interaction when a user types a hostname into a browser, and how different CDNs may improve each step:

-

DNS Resolution

- Traditional: Browser queries DNS for origin server IP, often with slow resolution times

- CDN Processed: CDN DNS infrastructure may use various routing strategies (anycast or unicast) to direct users to optimal edge servers. Some CDNs support modern DNS records like HTTPS or SVCB (Service Binding) records that can advertise protocol capabilities directly in DNS responses, though adoption varies across providers

-

Connection Establishment

- Traditional: Browser establishes new TCP connection to distant origin server with full handshake overhead

- CDN Processed: Connection to nearby edge server over TCP (for HTTP/1.1 and HTTP/2) or UDP with QUIC (for HTTP/3). CDNs may support HTTP/3’s 0-RTT connection resumption for returning visitors, though not all CDNs have implemented these newer connection optimization features

-

Protocol Negotiation

- Traditional: Limited to origin server’s protocol capabilities, often older HTTP versions

- CDN Processed: Many CDNs can advertise modern protocol availability through

Alt-Svc(Alternative Service) HTTP headers that inform browsers about alternative protocols. CDNs typically provide protocol translation benefits, accepting newer protocols from browsers while maintaining connections to origins, regardless of origin server capabilities

-

Request Processing & Optimization

- Traditional: Basic request forwarding with minimal processing

- CDN Processed: Depending on the CDN, may include header normalization, intelligent routing decisions, addition of performance headers like Server-Timing which provides server-side performance metrics, security headers, and request optimization based on content type and user geographic location

-

Response Processing

- Traditional: Direct response from origin server, limited by origin’s HTTP server capabilities

- CDN Processed: CDNs may implement advanced caching strategies, cache validation, Content-Encoding optimization (such as Brotli or Gzip compression), conditional request support (like 304 Not Modified responses that save bandwidth), and response transformation, though specific features vary by provider

-

Connection Management

- Traditional: Single connection per request or basic keep-alive to origin

- CDN Processed: Many CDNs implement dual-sided connection optimization, maintaining persistent connections to clients while using intelligent connection pooling to origin servers, reducing overhead on both ends

CDNs serve as deployment platforms for emerging web standards, implementing new HTTP headers, compression algorithms, and security features at scale before they become widely adopted by origin servers. This positions CDNs as critical infrastructure for web technology evolution, though the specific features and optimizations available depend significantly on the CDN provider and their technology adoption timeline.

Caveats and disclaimers

Our 2025 analysis builds upon the methodology established in previous years while incorporating new metrics and deeper performance analysis. The statistics gathered focus on applicable technologies and optimization patterns rather than vendor-specific performance comparisons.

Important note on measurements: All TLS negotiation times, DNS resolution times, and performance metrics in this analysis are measured from HTTP Archive’s simulated browser connections using Chrome on controlled infrastructure. These measurements represent:

- Consistent network conditions (controlled datacenter connectivity)

- Chrome browser’s TLS implementation

- First-time connections without session resumption

- Standardized measurement methodology across all CDNs

Real-world performance may vary based on geographic proximity to CDN edge servers, network conditions, TLS session resumption capabilities, and client device characteristics.

Key limitations of our testing methodology:

- Simulated network conditions: Tests use controlled network environments

- Single geographic perspective: Analysis from limited datacenter locations

- Cache effectiveness: Each CDN uses proprietary technology and many, for security reasons, do not expose cache performance or depth of cache

- Localization and internationalization: Just like geographic distribution, the effects of language and geographic specific domains are also opaque to these tests

- CDN detection: This is primarily done through DNS resolution and HTTP headers. Most CDNs use a DNS CNAME to map a user to an optimal data center. However, some CDNs use Anycast IPs or direct A+AAAA responses from a delegated domain which hide the DNS chain. In other cases, websites use multiple CDNs to balance between vendors, which is hidden from the single-request pass of our crawler

- Sampling bias: HTTP Archive data reflects popular websites, potentially overrepresenting certain CDN providers

- Market share interpretation: Our data shows CDN usage patterns among crawled sites, not true market distribution

CDN adoption

A web page is composed of the following key components:

- Base HTML page (for example,

www.example.com/index.html—often available at a more friendly name like justwww.example.com). - Embedded first-party content such as images, CSS, fonts and JavaScript files on the main domain (

www.example.com) and the subdomains (for example,images.example.com, orassets.example.com). - Third-party content (for example, Google Analytics, advertisements) served from third-party domains.

The evolution of CDN adoption patterns reflects the changing nature of web architecture and the increasing complexity of modern web applications. CDNs continue to prove their value across different content types, with varying adoption rates that reflect their suitability for different use cases.

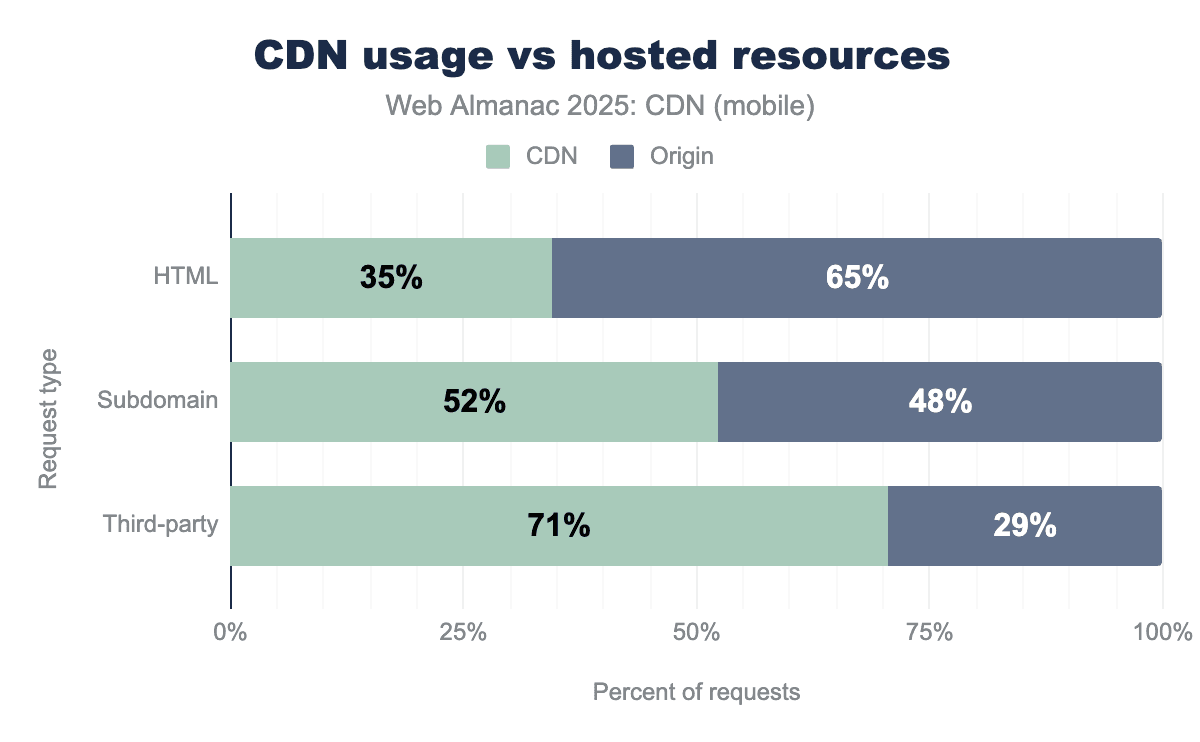

The chart shows the breakdown of requests for different types of content (HTML, Subdomain, and Third-party), showing the share of content served by CDN versus origin on mobile devices.

CDNs are often utilized for delivering static content such as fonts, image files, stylesheets, and JavaScript. This kind of content doesn’t change frequently, making it a good candidate for caching on CDN proxy servers. We still see CDNs used more frequently for this type of resource, especially for third-party content, with 71% being served via CDN. Subdomain resources show moderate CDN adoption at 52%, while HTML content has the lowest CDN usage at 35%, as it’s more commonly served directly from origin servers.

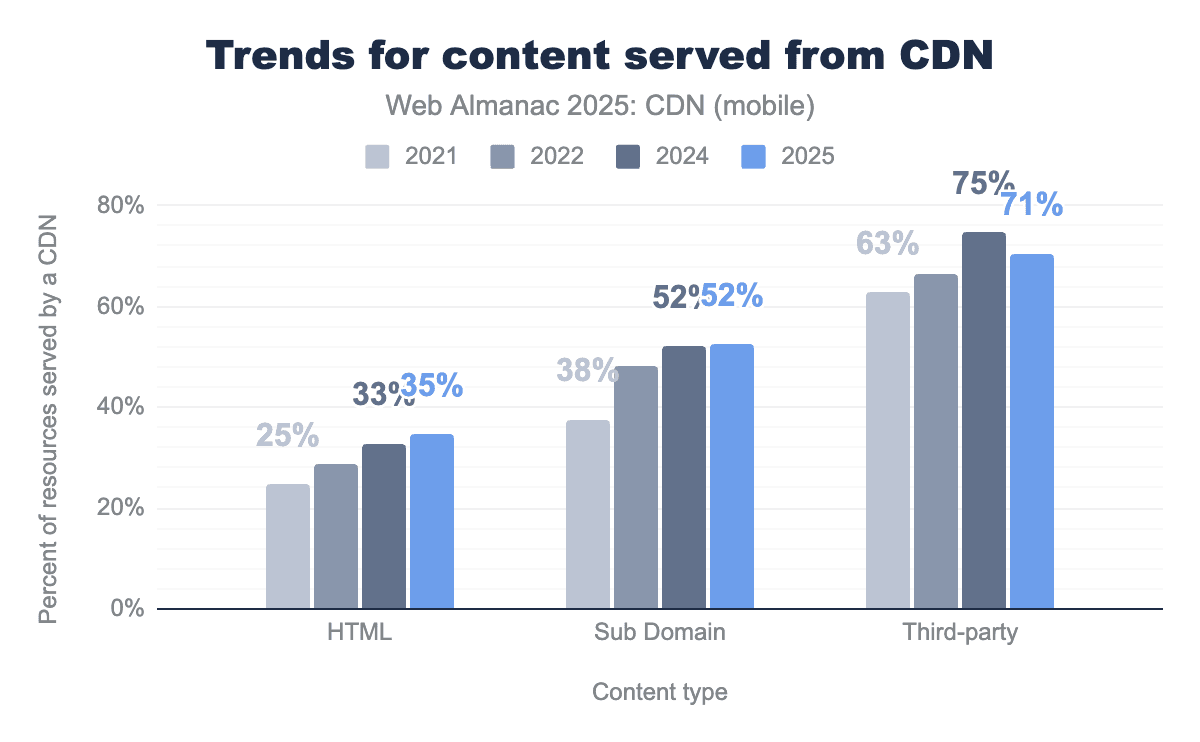

From 2024 to 2025, we see mixed trends across content types. HTML content continued its upward trajectory, increasing from 33% to 35%. Subdomain content remained stable at 52% in both years. However, third-party content experienced a notable decline from 75% in 2024 to 71% in 2025, representing a four percentage point decrease after years of consistent growth.

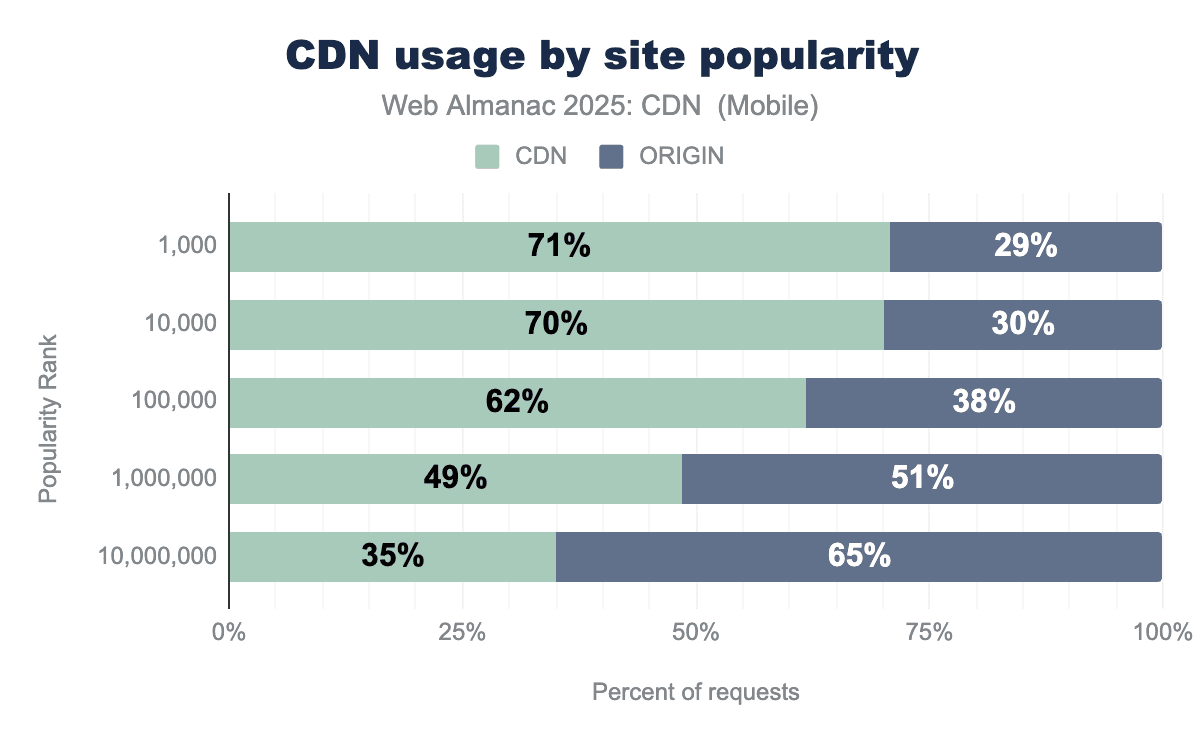

The share of CDN usage has increased over the years, particularly among the most popular websites according to Google Chrome’s UX Report (CrUX) classification. As the graph shows, the top 1,000 websites have the highest CDN usage at 71%, followed by the top 10,000 at 70%, and the top 100,000 at 62%. Compared to 2024, CDN adoption has increased regardless of popularity rank.

As mentioned in previous editions, the increase in CDN usage of 33% in 2024 to 35% in 2025 among smaller sites can be attributed to the rise of free or flat-tiered or affordable CDN options. Additionally, many hosting solutions now bundle CDNs with their services, making it easier and more cost-effective for websites to leverage this technology.

CDN providers

CDN providers can generally be classified into two segments:

- Generic CDNs: Providers that offer a wide range of content delivery services to suit various use cases, including Akamai, Cloudflare, Amazon CloudFront, and Fastly.

- Purpose-built CDNs: Providers tailored to specific platforms or use cases, such as Netlify and WordPress.

Generic CDNs address broad market needs with offerings that include:

- Website delivery

- Web application API delivery

- Video streaming

- Edge Computing services

- Web security offerings

These capabilities appeal to a wide range of industries, which is reflected in the data.

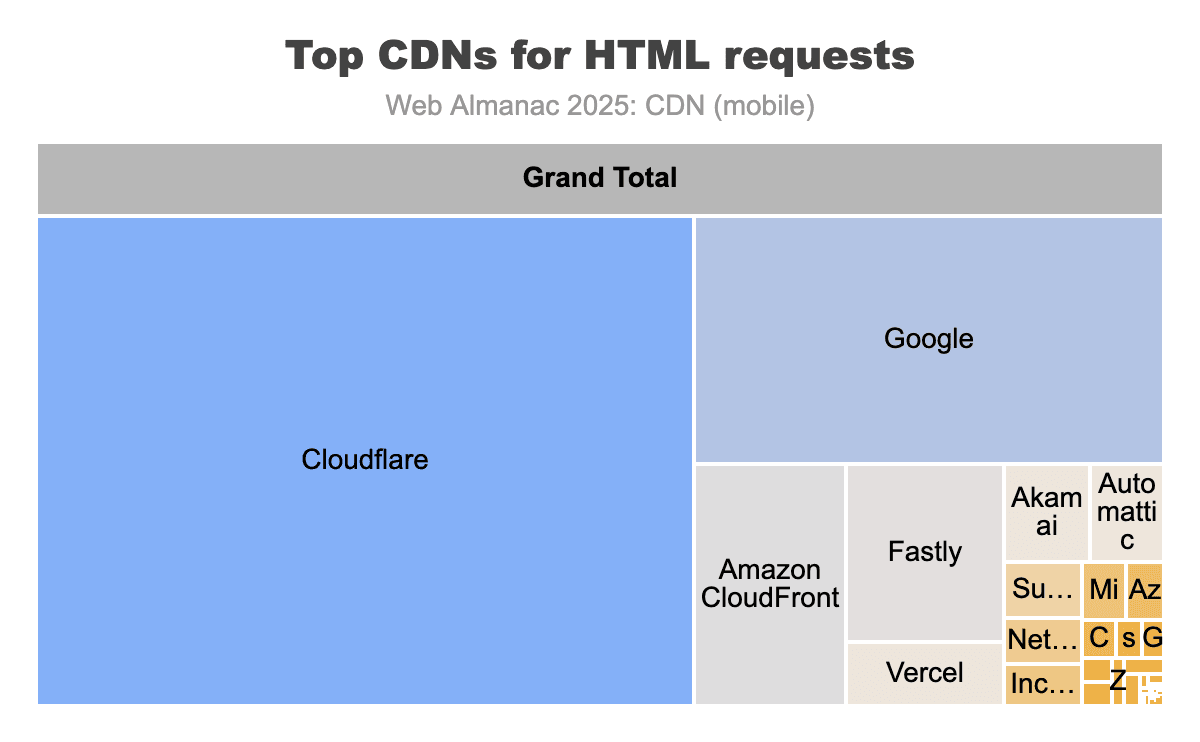

The leading vendors for serving base HTML requests are Cloudflare, with a 58% share, followed by Google (21%), Amazon CloudFront (7%), Fastly (5%), and Akamai and Vercel, each with a 2% share.

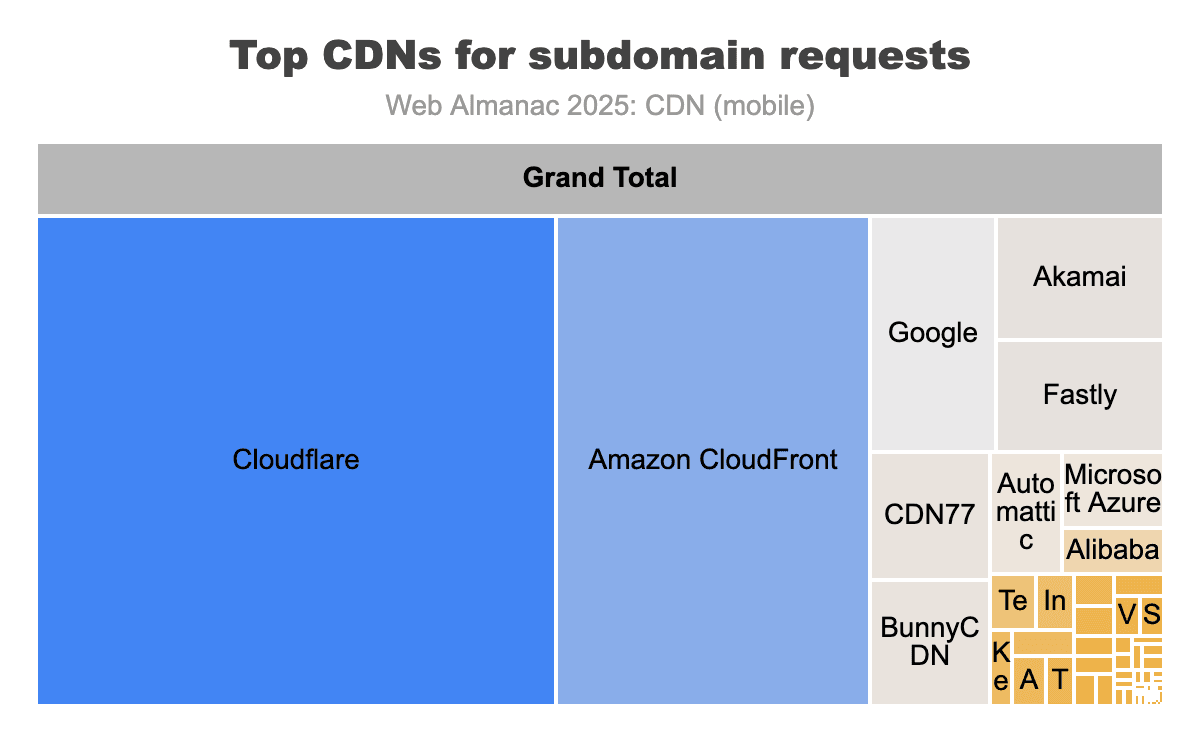

Marginally changing from 2024, the leading vendors in this category are Cloudflare (46%), Amazon CloudFront (28%), Google (5%), and Akamai (4%).

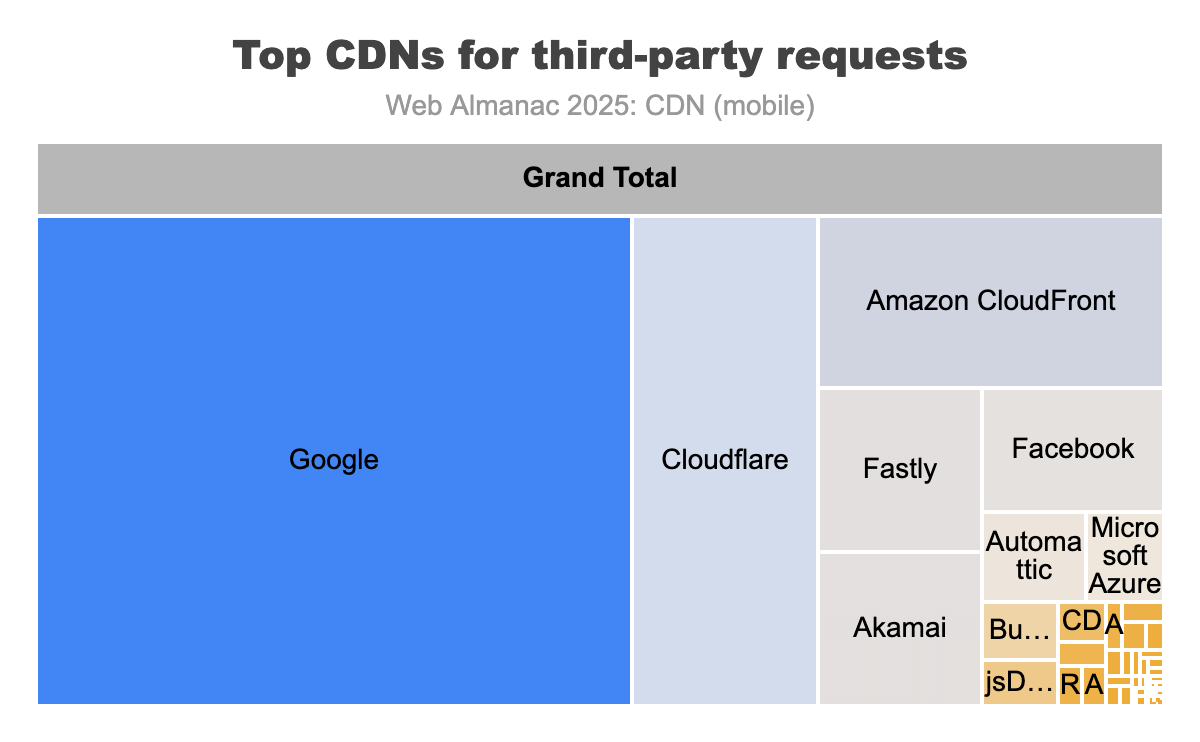

Google leads the list third-party domain usage at 53% market share, followed by well-known CDN providers such as Cloudflare (17%), Amazon CloudFront (11%), Fastly (5%), and Akamai and Facebook (4%).

While many CDNs offer purpose-built features optimized specifically for content delivery, they increasingly exist as part of larger service ecosystems. These CDNs are often tightly integrated with cloud infrastructure, security solutions, and edge computing platforms, with these adjacent services delivered through or alongside the CDN itself.

Different CDN providers take distinct approaches to optimization and specialization. Third-party platforms like Google and Facebook build highly specialized CDNs engineered specifically for their needs, handling massive throughput for ad delivery and capturing analytics beacons at scale. In contrast, general-purpose CDNs like Cloudflare and Amazon CloudFront optimize targeted feature sets while maintaining broader applicability. These platforms leverage their CDN capabilities as a foundation for managed services, enabling use cases such as globally distributed API gateways or real-time JavaScript injection for client-side device fingerprinting and security inspection.

HTTP/3 adoption

Published in June 2022 by IETF, HTTP/3 is a major revision of the HTTP network protocol, succeeding HTTP/2. The transition to HTTP/3 represents one of the most significant protocol upgrades in web history. Built on QUIC transport, HTTP/3 eliminates head-of-line blocking and reduces connection establishment overhead. Our 2025 analysis reveals dramatic shifts in adoption patterns, particularly among CDN providers.

HTTP/3’s performance improvements stem from fundamental protocol design changes that CDNs are uniquely positioned to leverage at global scale. Unlike HTTP/2’s reliance on TCP, HTTP/3 uses QUIC over UDP, eliminating TCP’s head-of-line blocking. When one HTTP/2 stream encounters packet loss, all multiplexed streams on that TCP connection stall. CDNs implementing HTTP/3 can maintain performance for unaffected requests through QUIC’s independent stream recovery. This is particularly valuable for CDNs serving mixed content where a slow loading image won’t block critical CSS or JavaScript delivery.

HTTP/3 reduces connection establishment from HTTP/2’s 3 RTTs (TCP handshake, TLS handshake, and HTTP negotiation) to 1 RTT through QUIC’s integrated cryptographic handshake. CDNs amplify this benefit through geographic proximity, as users connecting to nearby CDN edge servers experience reduced connection time. For returning visitors, some CDNs implement 0-RTT connection resumption, eliminating handshake overhead entirely when reconnecting to the same edge server.

Modern CDNs are beginning to implement HTTPS DNS records, a type of Service Binding (SVCB) / HTTPS records that allows DNS responses to advertise HTTP/3 availability and connection parameters directly. When a browser queries DNS for a CDN enabled domain, HTTPS records can indicate HTTP/3 support on port 443 with specific QUIC parameters, enabling immediate HTTP/3 connections without the traditional HTTP/2 to HTTP/3 upgrade process. This DNS level optimization is particularly powerful for CDNs managing multiple domains and services, as it eliminates protocol upgrade negotiations and can reduce connection establishment time. However, HTTPS record implementation varies significantly across CDN providers, with some leading adoption while others have not yet implemented support.

Important methodological considerations

Our HTTP/3 adoption measurements reflect the specific characteristics of HTTP Archive’s methodology and should not be interpreted as representative of overall internet traffic:

- Site Selection: Analysis focuses on popular websites (top 10M) that are more likely to implement modern protocols

- Resource Type Focus: Measurements primarily reflect static resources (CSS, JS, images) served by CDNs rather than main document loads

- Geographic Scope: Testing from limited datacenter locations may not reflect global user experience

- External Validation: Cloudflare’s own 2025 data reports ~21% HTTP/3 adoption globally, significantly lower than the 69% we observe for Cloudflare resources in our dataset

These measurements are valuable for understanding protocol adoption among leading web properties and CDN-served resources, but should not be extrapolated to represent general internet usage patterns.

HTTP/3 adoption among CDN providers

In 2025, using consistent methodology from previous years, we observed significant HTTP/3 adoption among CDN-served resources. While these numbers reflect the specific subset of sites and resources in our dataset, they demonstrate clear patterns in CDN protocol deployment:

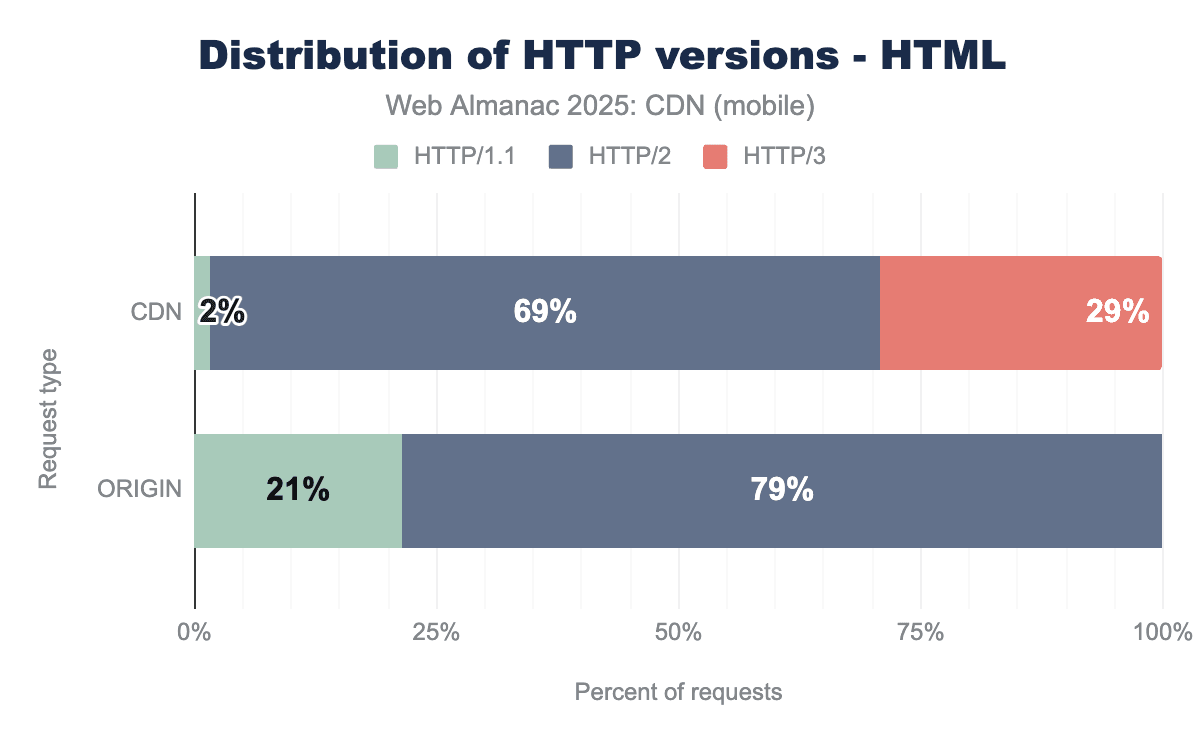

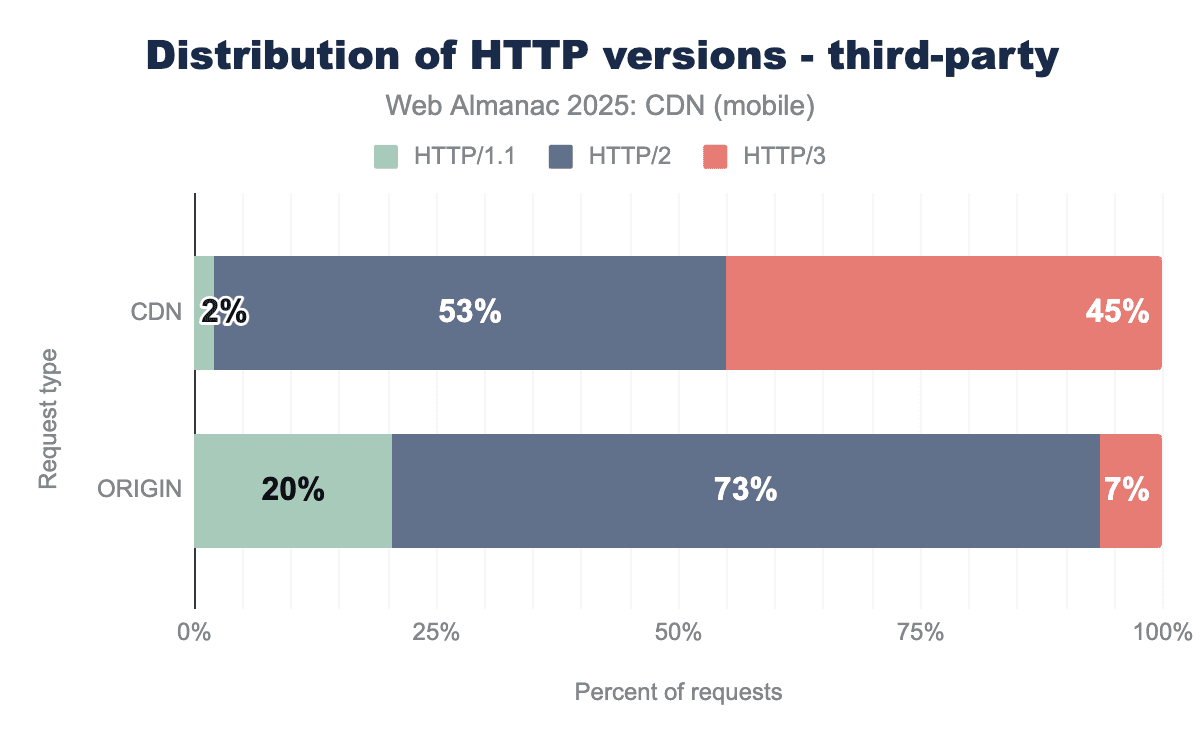

Within our dataset, the data reinforces the role CDNs play in driving the adoption of new protocols among popular websites and static resources. CDNs saw 29% traffic from HTTP/3 with effectively 0% for origin traffic. Compared to 2024, we observed a sharp decrease in CDN usage for HTTP/1.1 in 2025.

While HTTP/1.1 usage has been on a continued decline with CDNs over the past several years, in 2025 we observed a sharp decrease in CDN usage for HTTP/1.1 going from 16% usage for HTML requests in 2024 to just 2% in 2025. This decrease was even more pronounced for origin requests with 56% HTTP/1.1 requests in 2024 down to 21% in 2025.

Looking at individual CDNs HTTP/3 support we see the following for documents (often the initial requests):

| CDN | Desktop | Mobile |

|---|---|---|

| Cloudflare | 44.0% | 49.9% |

| CDN | 6.2% | 5.0% |

| Amazon CloudFront | 3.2% | 3.8% |

| Sucuri Firewall | 0.5% | 0.6% |

| Akamai | 0.2% | 0.2% |

| QUIC.cloud | 0.1% | 0.1% |

| 0.1% | 0.1% |

Special call out to Cloudflare who are leading the industry here.

While subresources requests have a much higher rate of adoption since they often are used for multiple requests where subsequent requests are more likely to be made over HTTP/3:

| CDN | Desktop | Mobile |

|---|---|---|

| 99.4% | 99.9% | |

| Nexcess CDN | 97.7% | 99.6% |

| Sucuri Firewall | 71.2% | 68.4% |

| Cloudflare | 68.6% | 69.5% |

| Reapleaf | 59.5% | 59.1% |

| Erstream | 31.5% | 77.4% |

| QUIC.cloud | 48.8% | 47.3% |

| 39.6% | 42.2% | |

| Pressable CDN | 40.1% | 40.8% |

| Automattic | 25.6% | 29.0% |

CDN Performance

CDN performance extends beyond simply caching content closer to users. CDNs actively optimize the underlying protocols and connection mechanisms that determine how quickly browsers can establish connections and receive data while providing transparent metrics to understand bottlenecks in modern web applications. Performance optimization techniques include connection pooling, protocol translation, and intelligent routing—all of which contribute to reduced latency and improved user experience.

HTTP/3 TTFB Performance

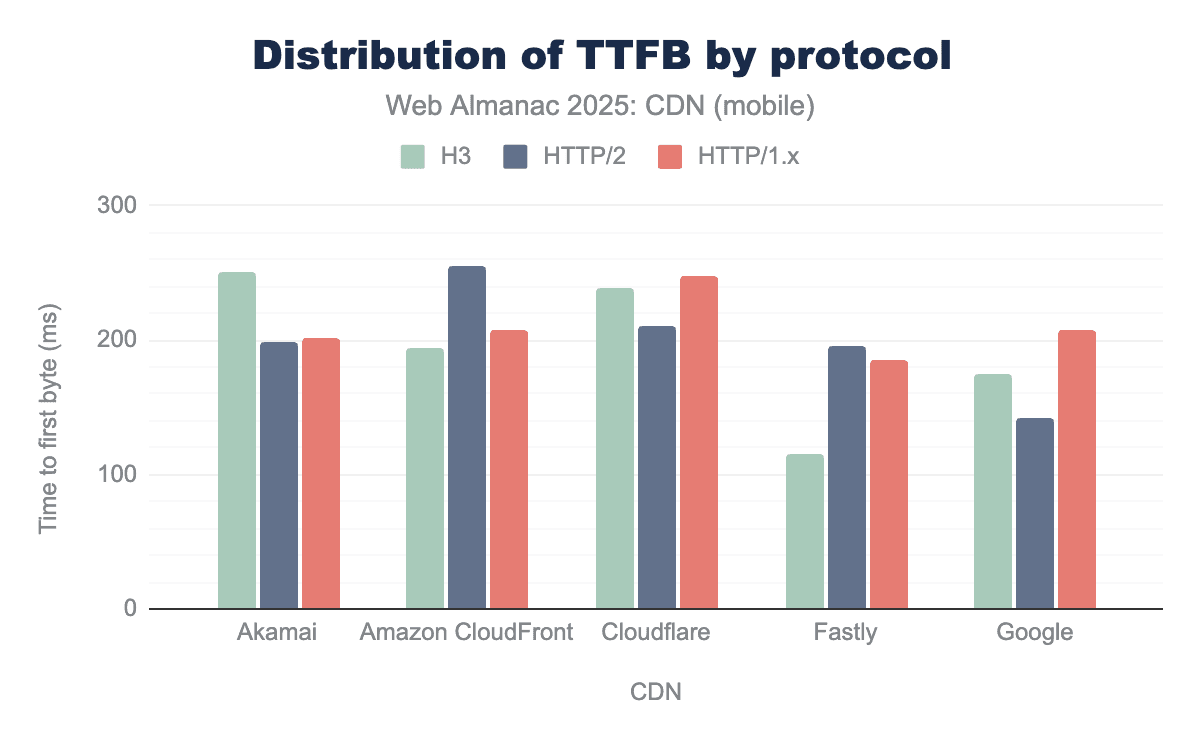

Below shows the time to first byte (TTFB) median percentile distribution for latency of HTTP/3, HTTP/2, and HTTP/1.1 across major CDNs. These measurements reflect simulated browser connections and may vary from real-world performance.

The TTFB performance for HTTP/3 compared to previous HTTP protocol versions varies by CDN provider, with Amazon CloudFront and Fastly both showing improved TTFB latency. Note that these are not uniform tests across CDNs and website owners should perform their own controlled performance testing.

DNS Performance

DNS resolution is the critical first step in any web request. Our 2025 data shows significant performance advantages for CDNs over origin servers:

DNS Resolution Performance (Median):

-

CDN (Mobile): 176ms

-

Origin (Mobile): 217ms

-

CDN advantage: 19% faster

-

CDN (Desktop): 52ms

-

Origin (Desktop): 129ms

-

CDN advantage: 60% faster

The desktop performance advantage is particularly striking, with CDNs delivering DNS responses 2.5x faster than origin servers. This improvement stems from CDNs’ use of anycast routing, extensive edge networks, and optimized DNS infrastructure.

Alt-Svc

The Alt-Svc (Alternative Services) HTTP response header tells browsers about alternative protocols or servers they can use to access the same resource. The most common use case is advertising HTTP/3 support. When a browser first connects to a server using HTTP/1.1 or HTTP/2, the server can include an Alt-Svc header like: Alt-Svc: h3=":443"; ma=86400

This informs the browser that it can use HTTP/3 on port 443 to reach the same service, and that this information remains valid for 86400 seconds (24 hours). Once the browser receives this header, it can establish future connections using HTTP/3 directly rather than beginning with HTTP/2 and negotiating an upgrade.

Our 2025 data shows:

- Google HTTP/2 → H3 advertising: 99.2% (44M HTTP/2 requests advertising HTTP/3)

- Cloudflare HTTP/2 → H3 advertising: 100% (44M HTTP/2 requests advertising HTTP/3)

- Amazon CloudFront HTTP/2 → H3 advertising: 100% (28M HTTP/2 requests advertising HTTP/3)

- Origin servers HTTP/2 → H3 advertising: 99.89% (54M HTTP/2 requests advertising HTTP/3)

The data demonstrates that CDNs using HTTP/2 nearly universally advertise HTTP/3 availability through Alt-Svc headers, enabling browsers to upgrade to HTTP/3 for subsequent requests. This widespread protocol advertising helps drive the broader adoption of HTTP/3 across the web.

Server-Timing

Defined in the W3C Server-Timing specification, the Server-Timing HTTP header allows servers to communicate performance metrics about request processing back to the browser. This header communicates performance metrics directly, transforming opaque server processing into observable and debuggable data. Specific to CDNs, Server-Timing headers can be useful for providing transparency into CDN edge processing time, origin fetch duration, or cache status without requiring additional monitoring infrastructure.

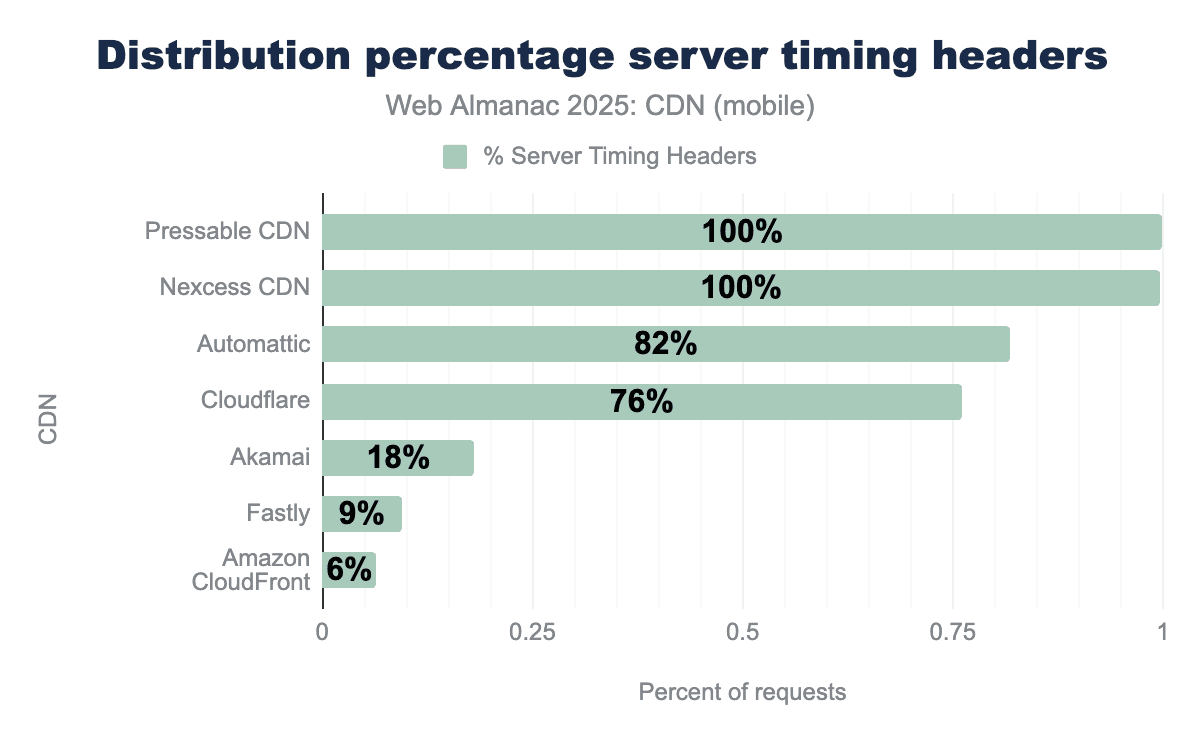

Adoption of the Server-Timing header varies across CDNs. We see Pressable and Nexcess CDNs had 100% adoption across their requests due to default configurations. CDNs like Akamai, Amazon CloudFront, and Fastly require non-default configuration likely leading to less adoption. However, enterprise concerns around security, privacy, and performance may drive this opt-in approach.

CDN Security Headers

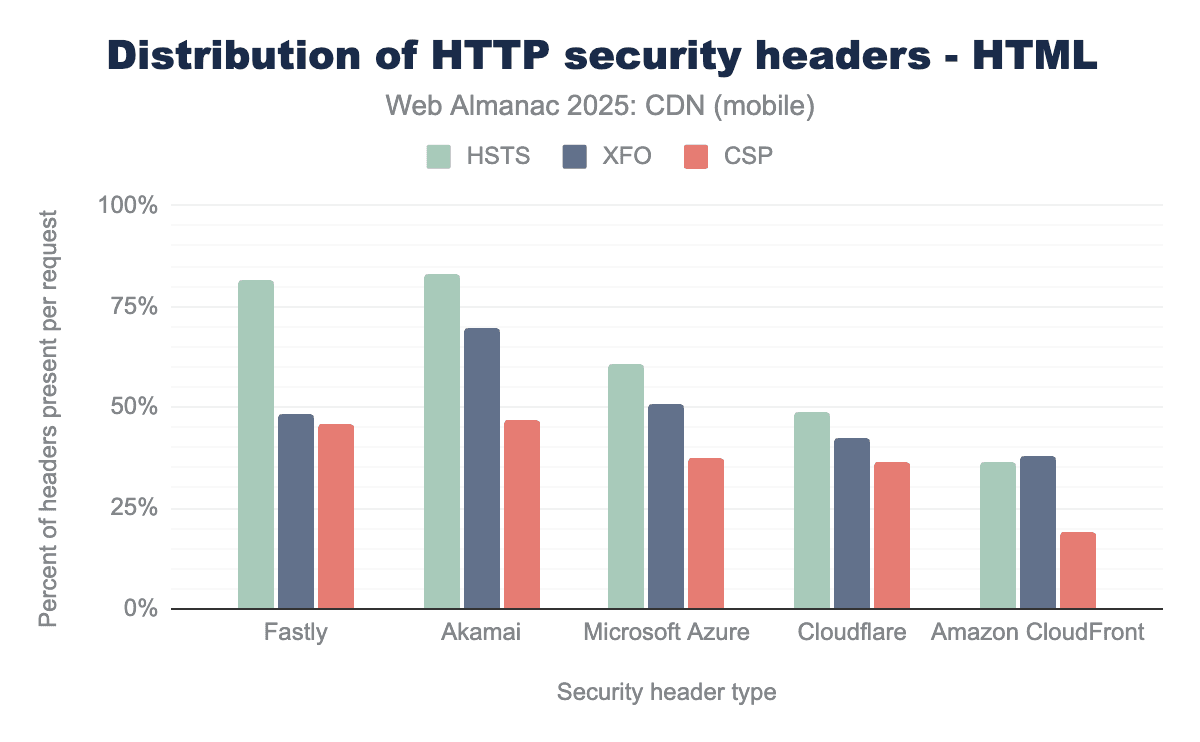

CDNs play a critical role in web security by implementing and enforcing security headers that protect users from common attacks. Security headers like HTTP Strict Transport Security (HSTS), X-Frame-Options (XFO), and Content Security Policy (CSP) help prevent everything from man-in-the-middle attacks to clickjacking and cross-site scripting. Because CDNs sit between users and origin servers, they can insert or modify these headers regardless of what the origin provides, making it easier for site operators to deploy security best practices.

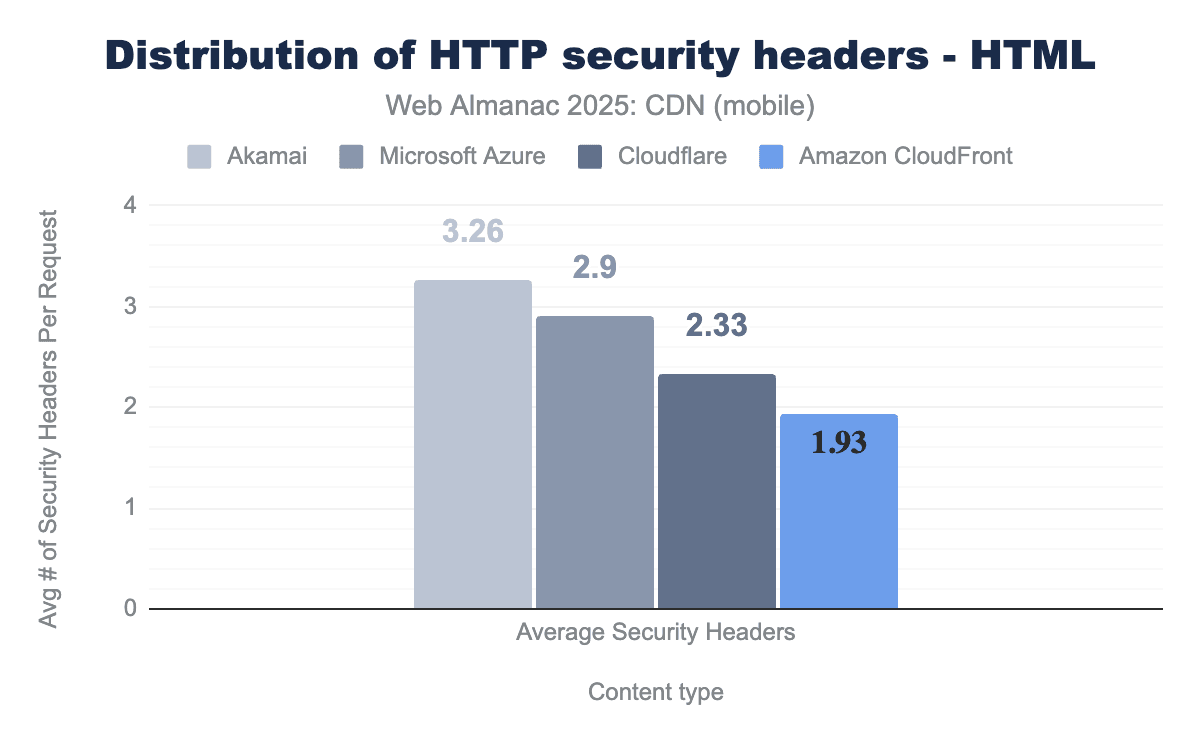

Security implementation varies significantly across CDN providers, reflecting different philosophies about defaults versus configurability. Some providers automatically inject security headers, while others require explicit configuration, balancing security with flexibility.

Both Cloudflare and Amazon CloudFront have a lower average number of security headers and this trend continues as we go more granular into specific headers as seen below. Header count is not a direct proxy for security posture; it often reflects how much a CDN auto-injects vs requires explicit configuration.

Fastly and Akamai have more secure defaults for security headers when basic features are enabled which drives higher rates of security headers. Amazon CloudFront and Cloudflare require more non-default configurations to inject and enforce security headers leading to a lower adoption.

Compression

Compression continues to be essential for web content delivery, representing one of the most accessible performance optimizations available for websites. Smaller file sizes mean faster page loads, lower bandwidth costs, and a better experience for users. Even as network speeds improve and connectivity options expand, compression remains important for optimizing performance across all types of internet connections.

Modern compression algorithms offer significant improvements over traditional methods, with CDNs leading the adoption of these advanced techniques. The choice of compression algorithm involves trade-offs between compression ratio, CPU usage, and compatibility requirements.

From the 2025 dataset we observed several commonly used compression algorithms:

- Gzip: The legacy standard, widely compatible but less efficient

- Brotli: Modern algorithm offering 20-26% better compression than Gzip

- Zstandard (Zstd): Emerging standard with excellent compression ratios and speed

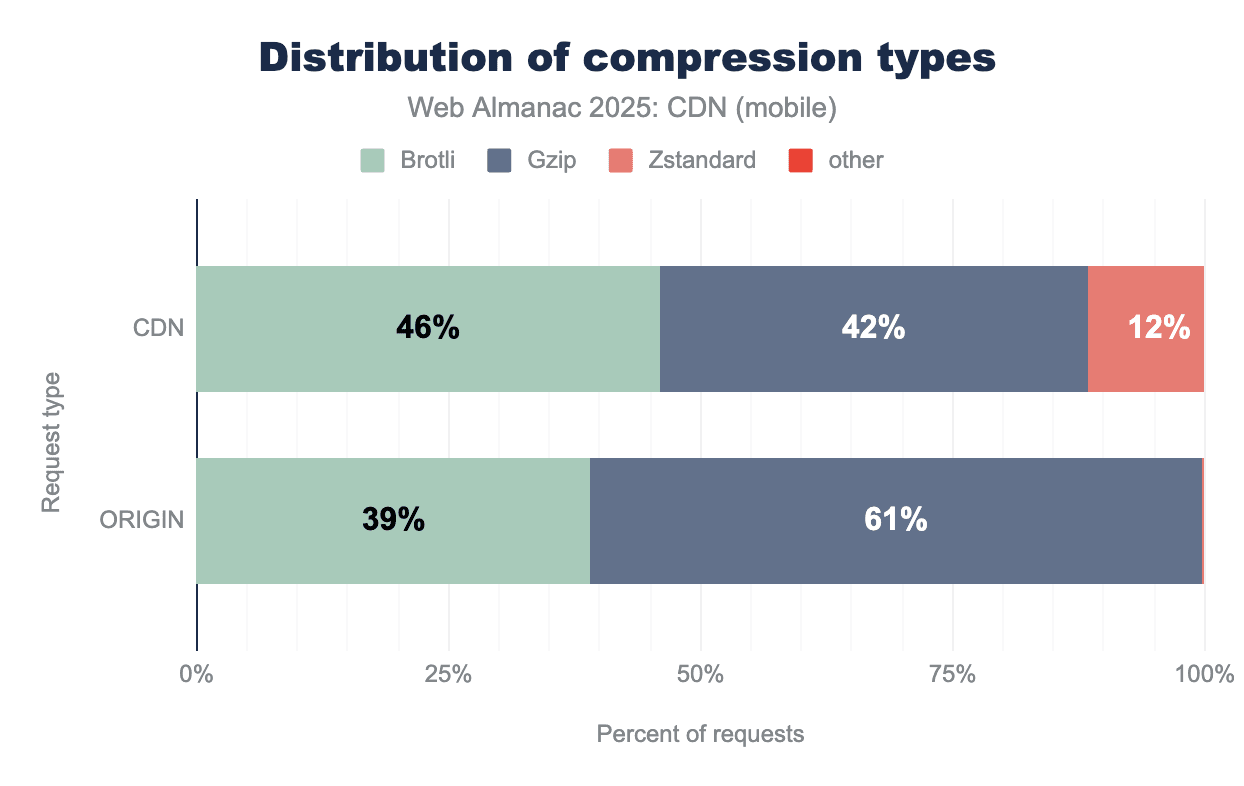

CDNs are leading the adoption of Brotli and Zstandard compression. Compared to 2024, Zstandard saw a significant increase from 3% to 12% in 2025. However, similar to 2024 Gzip remains the majority compression algorithm used by origin servers (61% Gzip vs 39% Brotli).

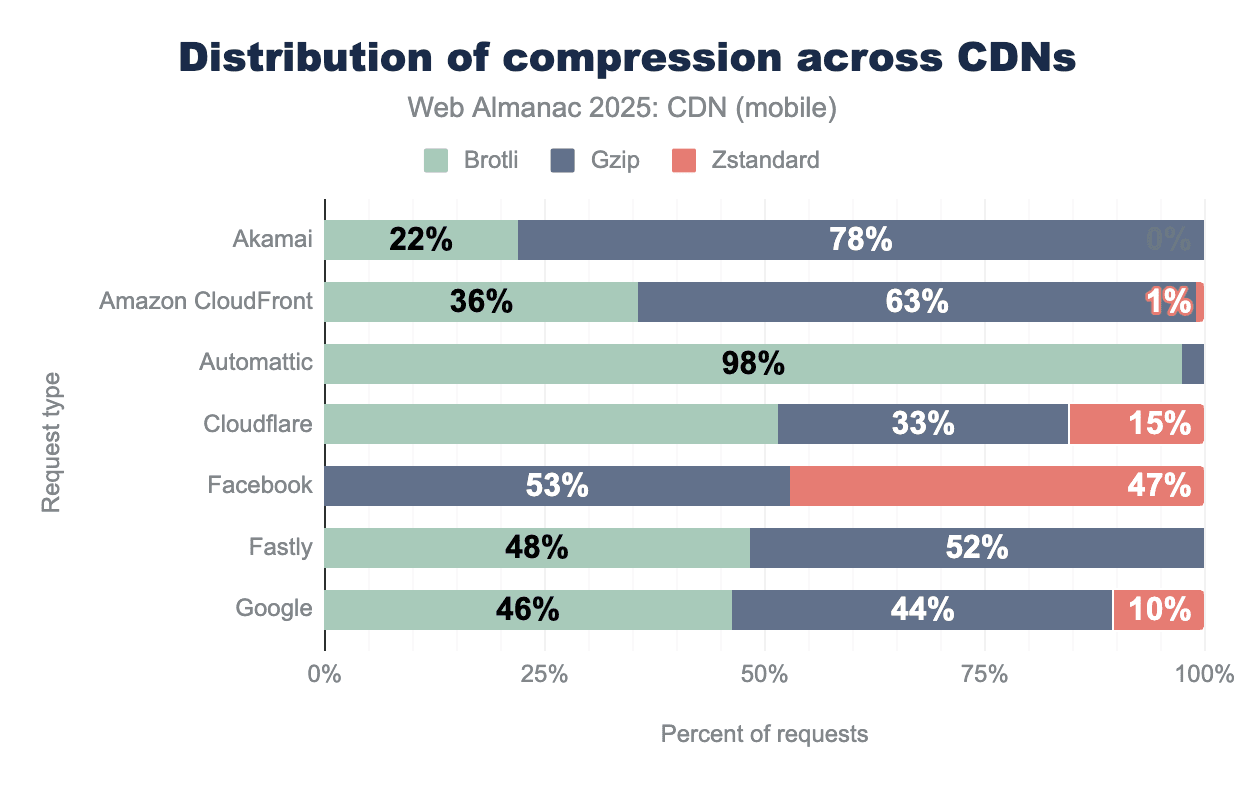

Special credit to Automattic with 98% of their eligible resources being served using Brotli!

While still in 3rd place in terms of adoption, Zstandard has made gains in 2025 compared to 2024. In 2024, only Facebook’s CDN had any statistically measurable usage of Zstandard, while in 2025 both Cloudflare (15%) and Google CDN (10%) showed measurable adoption. Cloudflare’s newer compression defaults and configuration options may help explain the observed data. The outliers to the dataset were Amazon CloudFront and Automattic, which currently do not support Zstandard compression natively. However, the data observed showed CloudFront passing through already compressed data from origin using Zstandard. This demonstrates content owner’s desire to use Zstandard even though not all major CDN providers support it.

Future compression trends

Looking ahead, the industry is exploring Dictionary Compression (Shared Brotli) which promises:

- 20-40% better compression for repeated content patterns

- Shared dictionaries across related resources

- Chrome Origin Trial launched in 2024

- Expected CDN support rollout in 2025-2026

This represents the next frontier in compression optimization, building on Brotli’s success and is one to watch in future editions of the Web Almanac.

TLS usage

Transport Layer Security (TLS) forms the foundation of secure web communications. CDNs have consistently led the adoption of newer TLS versions, providing enhanced security and performance benefits to websites without requiring infrastructure upgrades.

TLS 1.3 adoption

TLS 1.3 improves the overall security of web traffic compared to earlier versions that included weaker cryptographic algorithms that had known vulnerabilities. The protocol also reduces handshake latency through its optimized design.

Note on TLS 1.0 and 1.1 Absence: Our measurements show zero usage of TLS 1.0 and 1.1 across all requests. This is expected because HTTP Archive uses modern Chrome browsers for measurement, which completely removed support for these deprecated protocols in July 2020 (Chrome 84). Servers that only support TLS 1.0 or 1.1 would result in connection failures rather than successful requests, thus not appearing in our data. While these legacy protocols may still exist in some enterprise environments or IoT devices, they are no longer viable for public web services accessed by modern browsers.

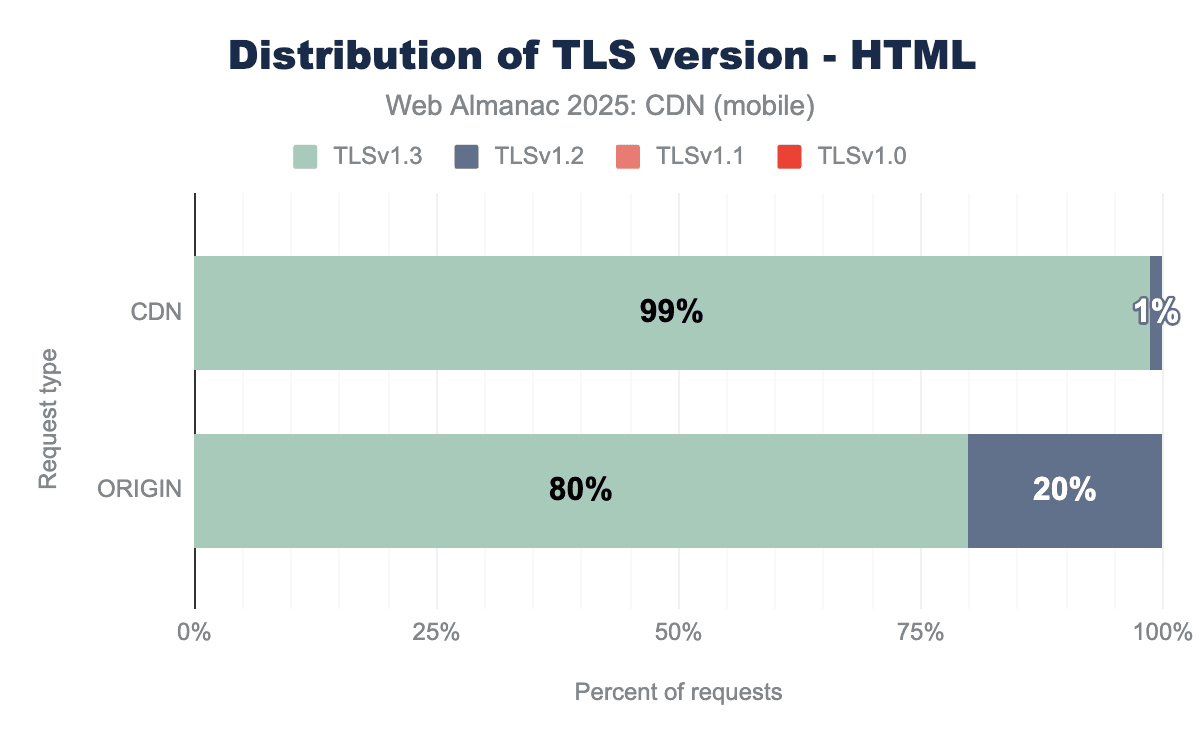

Nearly all CDN traffic now uses TLS 1.3, with 99% of requests leveraging the latest protocol version. This benefits developers through faster connection establishment times, directly improving page load speeds. CDN providers continue to be early adopters of new web technologies, which means applications using CDNs get these performance and security enhancements with little to no additional effort.

Though origin server adoption of TLS 1.3 is improving, CDNs still demonstrate a clear advantage in rolling out new capabilities compared to organizations managing their own software and hardware upgrades.

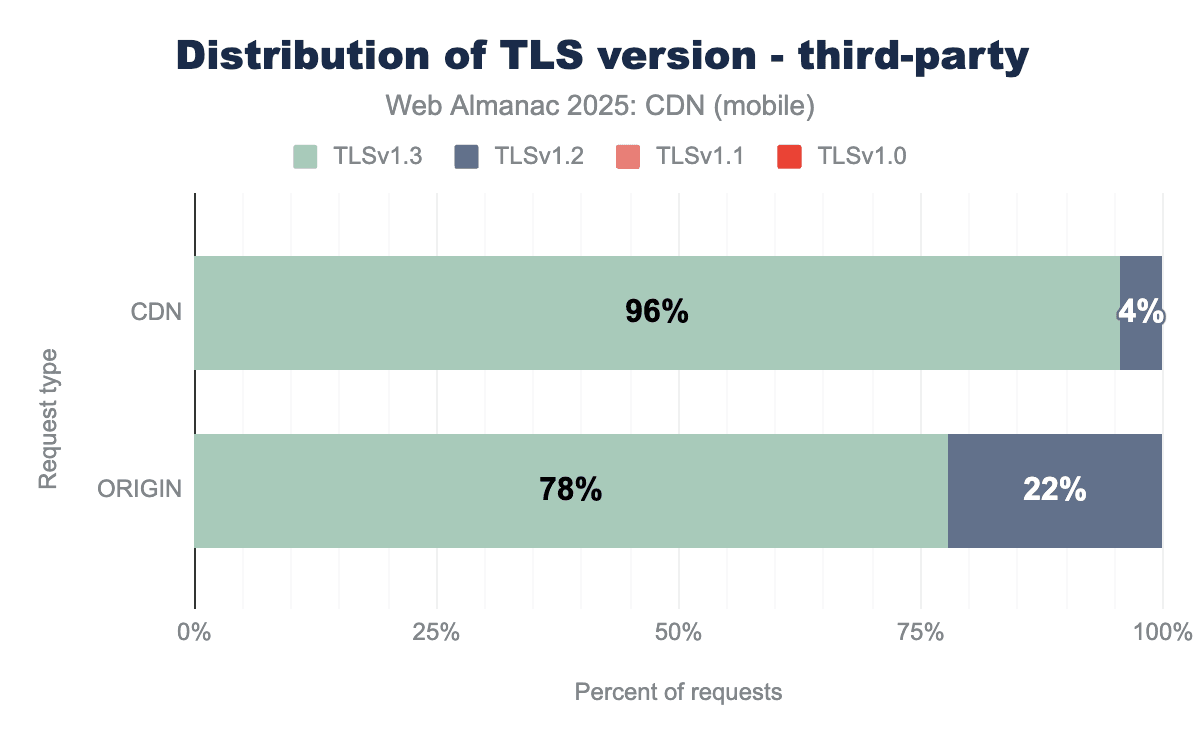

Third-party content shows a similar pattern, with 96% of CDN requests using TLS 1.3 compared to 78% for origin servers. CDN adoption increased modestly from 93% in 2024 to 96% in 2025, while origin servers saw a larger jump from 68% to 78% over the same period.

TLS performance impact

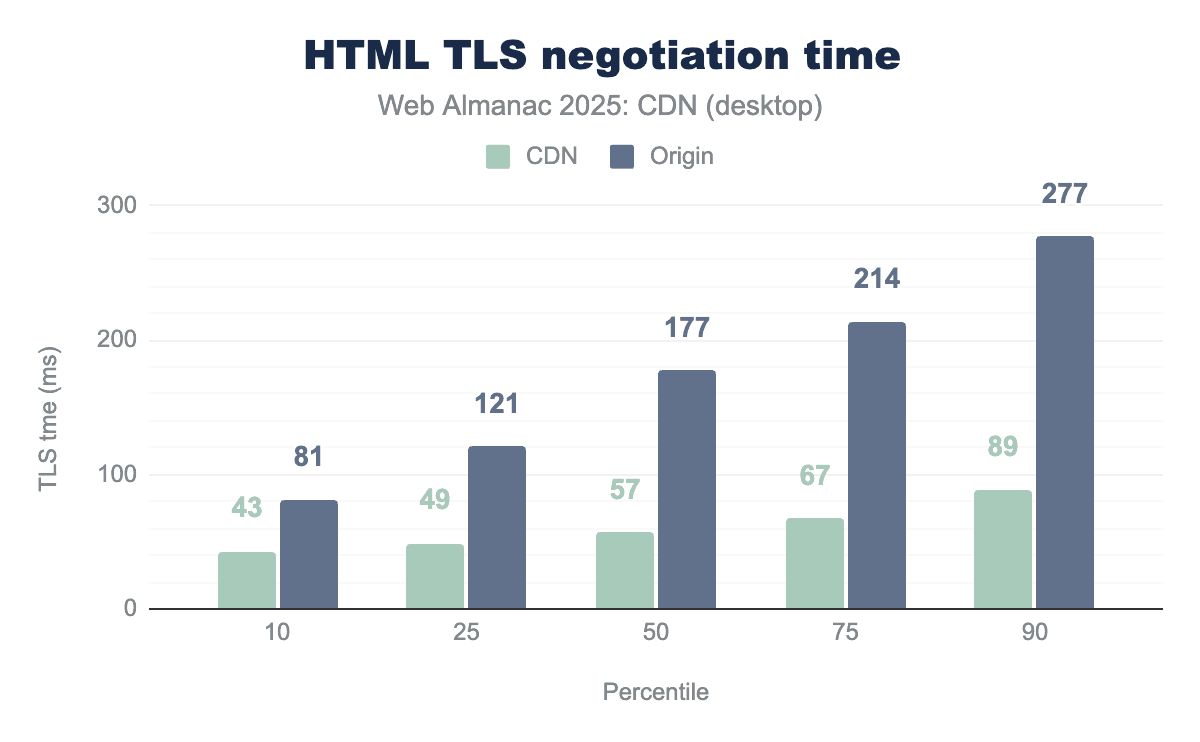

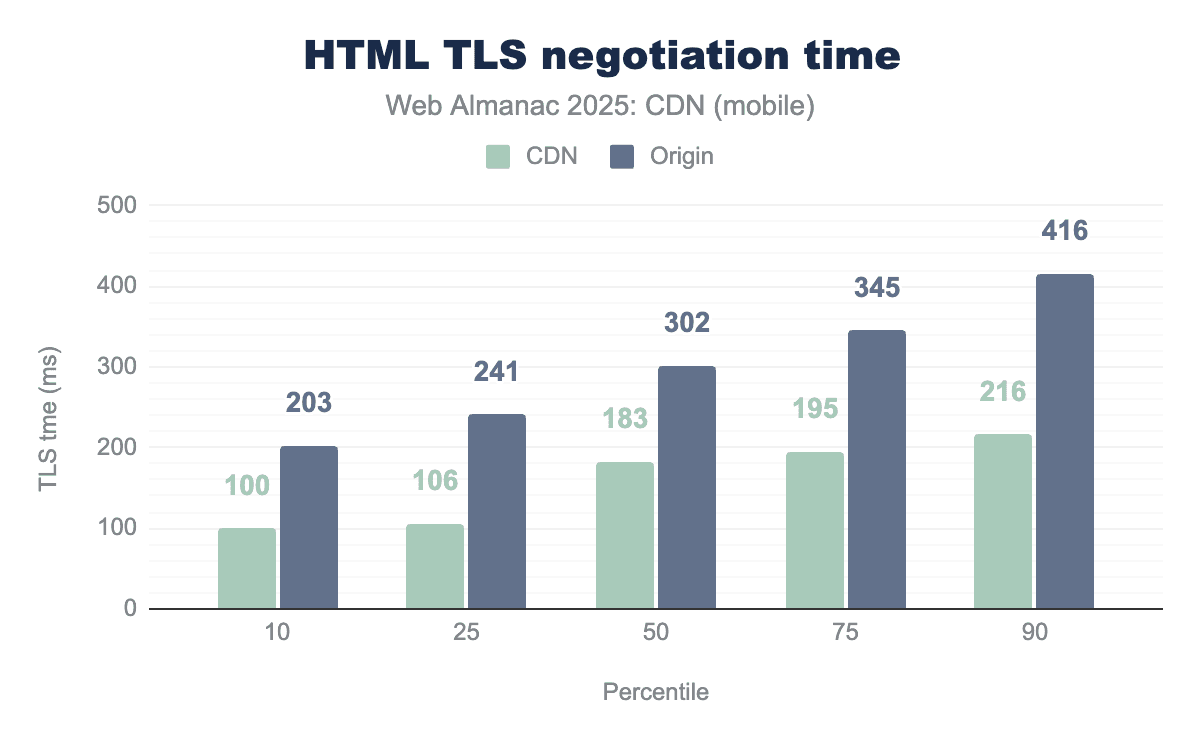

Important Measurement Context: The following TLS negotiation times are measured from HTTP Archive’s simulated browser connections using Chrome in controlled datacenter conditions. These measurements represent optimal network conditions and Chrome’s TLS implementation, which may not reflect real-world variations in client capabilities, network quality, or geographic distribution. Additionally, since Chrome no longer supports TLS 1.0/1.1, these measurements only capture TLS 1.2 and 1.3 performance characteristics.

TLS negotiation times show clear performance differences between CDNs and origin servers, with additional variations between desktop and mobile connections.

Desktop users experience substantially faster TLS negotiations with CDNs compared to origin servers at every performance level. The median negotiation time for CDNs is 57 milliseconds versus 177 milliseconds for origins, over three times faster. This performance gap persists across the distribution. At the 90th percentile, CDNs complete negotiations in 89 milliseconds while origins require 277 milliseconds.

Mobile devices show a similar pattern, with CDN performing better than origin servers, but the overall negotiation times are higher compared to desktop. The median TLS negotiation time for mobile CDN is 183 milliseconds, while for origin servers it’s 302 milliseconds. At the 90th percentile, mobile CDN takes 216 milliseconds, whereas origin servers require 416 milliseconds.

Mobile devices generally show slower performance than desktop due to their more limited processing power and often less reliable network conditions. CDNs outperform origin servers largely because of their distributed architecture, which positions content geographically closer to users and optimizes connection paths for reduced latency.

Image formats and optimization

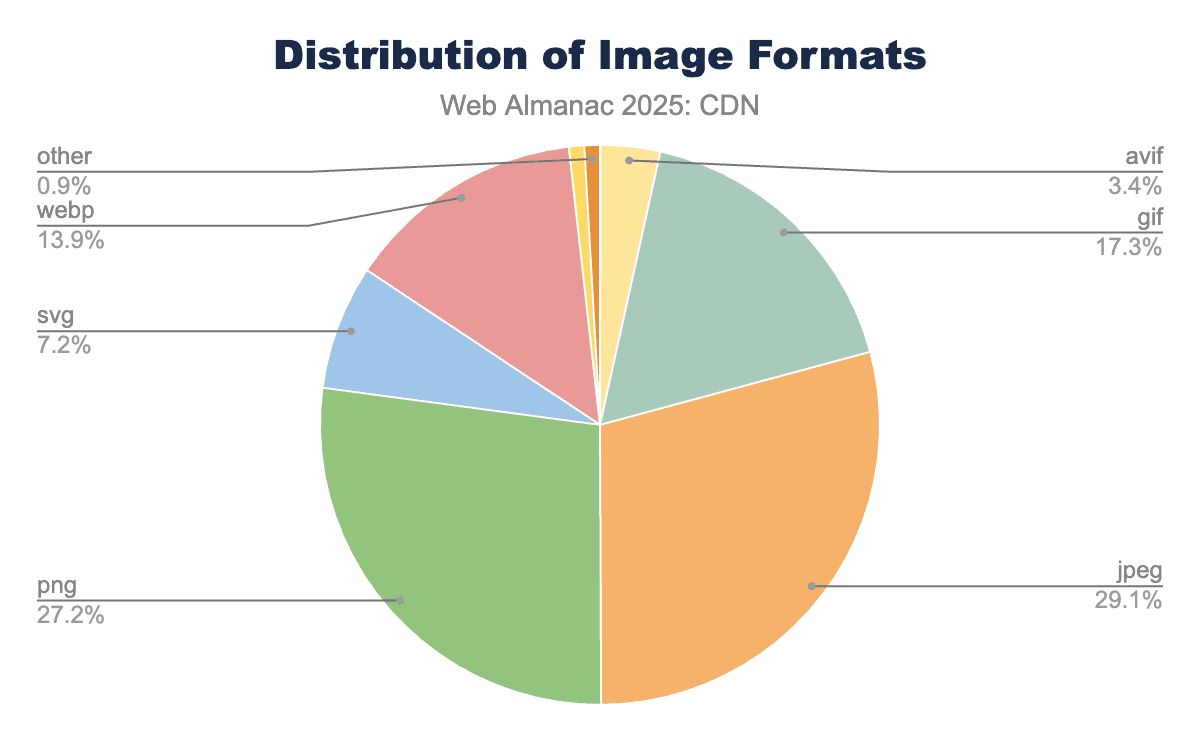

Image formats continue to play a pivotal role in CDNs, directly influencing website performance, bandwidth costs, and overall user experience. Modern formats such as WebP, AVIF, and SVG remain the most efficient options, offering improved compression ratios and visual fidelity compared to legacy formats like JPEG and PNG. These efficiencies translate to faster page loads and lower data transfer, especially critical for mobile users and high-traffic sites.

Most CDNs now automatically detect browser capabilities and serve the most optimized format available—for example, AVIF for Chrome, WebP for Edge, and JPEG fallback for legacy browsers. Adaptive resizing, caching, and on-the-fly conversion have largely eliminated the need for maintaining static image variants across device types or resolutions.

As of 2025, the data reflects a continued shift toward efficiency driven formats. While JPEG remains the most requested format, it declined by nearly 10% overall compared to 2022, with an even sharper 10.5% drop on mobile. Conversely, WebP (+5%), SVG (+2.5%), and AVIF (+3.1%) have all grown steadily since 2022. This may reflect shifts in site mix, image pipeline defaults, or fallback behavior rather than a reversal in industry support.

The GIF format showed a modest 2.3% increase, particularly on mobile (+0.5% higher than desktop), likely driven by short-loop animations and UI elements common in app-driven web traffic. Meanwhile, PNG usage saw a minor decline (-0.8%), suggesting designers and developers continue to prioritize lighter formats for both vector and raster assets.

Between 2024 and 2025, there was a slight regression in AVIF (-1.9%), SVG (-1.1%), and WebP (-1.8%), offset by small rebounds in GIF (+2.3%) and JPEG (+2.2%), a possible indicator of fallback scenarios or compatibility defaults on less optimized delivery stacks.

The 2025 data underscore a clear trajectory: legacy formats like JPEG still dominate total requests but are gradually ceding share to newer, more efficient formats. WebP, SVG, and AVIF are becoming the new baseline for high performance content delivery, especially in mobile-first ecosystems where latency and bandwidth efficiency are critical.

Client Hints

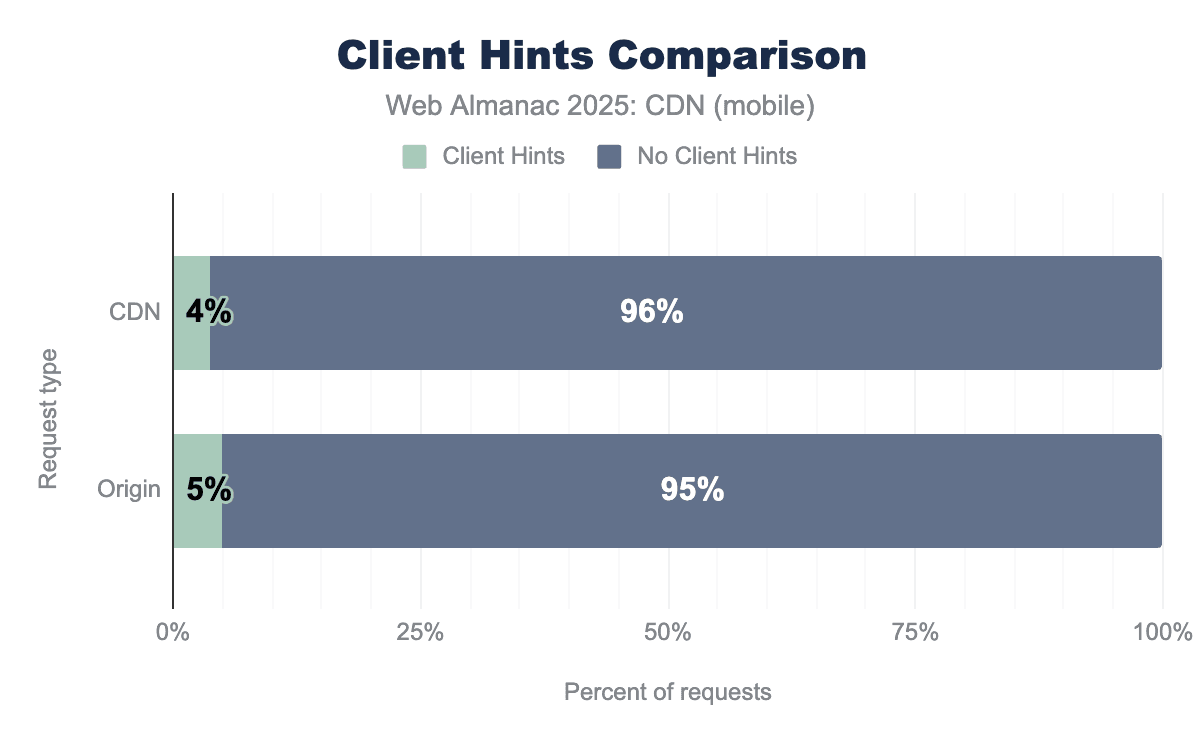

Client Hints were introduced as an alternative to the User-Agent string, letting web servers request specific information from browsers through HTTP headers. They fall into four main categories: device information, user agent preferences, user preference media features, and networking details. These hints are further split into high and low entropy types. High entropy hints can potentially be used for fingerprinting, so browsers usually require user permission or enforce other policies before sharing them. Low entropy hints are less useful for fingerprinting and may be sent by default based on browser or user settings.

In 2025, we continued measuring Client Hints using the same methodology established in 2024 - detecting the Accept-CH header in responses.

Client Hints buck the usual pattern of CDNs leading adoption: CDN usage was flat year-over-year, while origin requests increased to ~5% in 2025. A likely contributor is cache-key explosion at the edge, which can reduce cache hit rates when Client Hints are incorporated without careful bucketing. This challenge may explain why adoption remains low despite the technology’s potential benefits.

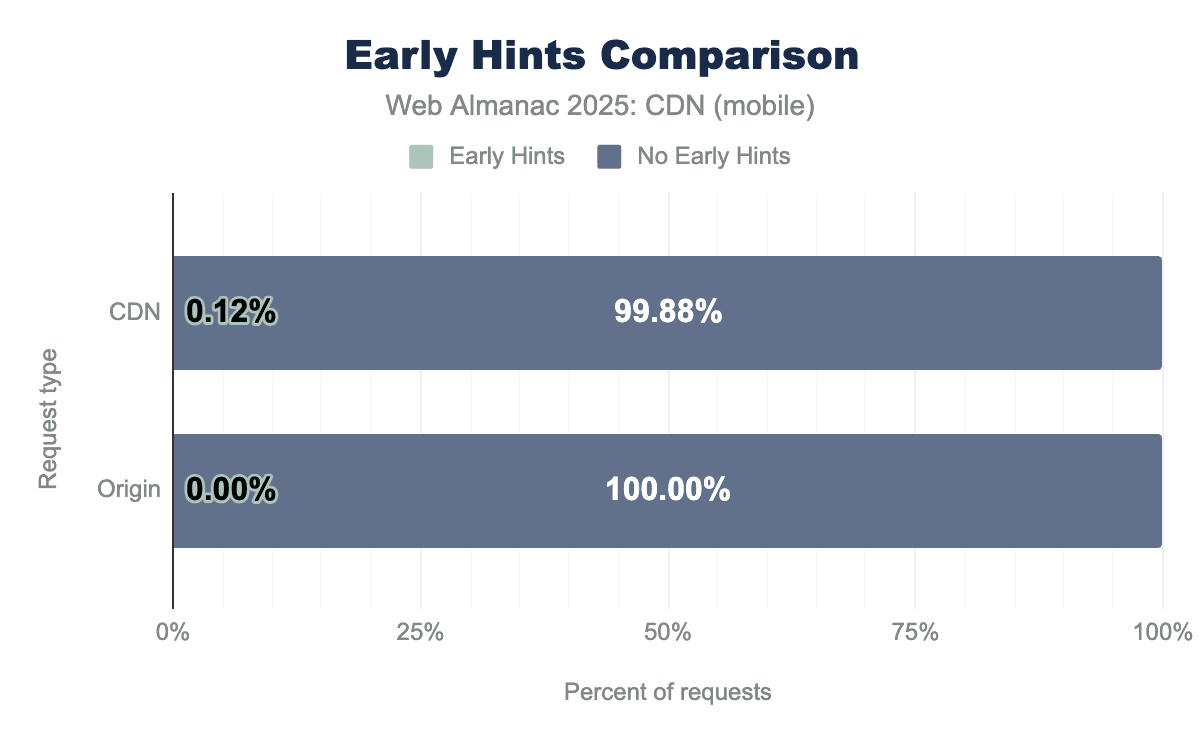

Early Hints

Early Hints uses the HTTP 103 status code to let servers send initial headers to browsers while the main response is still being prepared. This is especially useful for preloading important resources like stylesheets, JavaScript files, and fonts before the full page is ready. Despite its potential for improving performance, adoption remains minimal.

Browser support for Early Hints is widespread, but we found minimal usage in the dataset with only 0.012% of CDN requests. This represents a marginal 0.002% increase from 2024 to 2025. Vercel was the only CDN to support over 1% adoption (2.84%) with Cloudflare and Fastly less than 1%.

We’re interested to see how Early Hints affects performance as more sites start using it. Hopefully by next year’s Web Almanac, we’ll have more CDN providers implementing the feature and enough data to share detailed statistics on its impact.

Conclusion

In 2024, we saw CDNs leading the charge on adopting emerging technologies like HTTP/3, and that pattern has held steady into 2025. Looking at features like Brotli and Zstandard compression or TLS 1.3 encryption, CDNs make it easy for sites to implement these improvements through simple configuration changes instead of overhauling entire fleets of servers, load balancers, and networking equipment.

Our 2025 analysis reveals that CDNs have become the vanguard of web protocol evolution, with leading providers like Cloudflare achieving 69% HTTP/3 adoption compared to less than 5% for origin servers. This 10-15x difference demonstrates how edge infrastructure drives the adoption of next-generation web standards.

Key findings from our 2025 analysis include:

- Protocol Leadership: CDNs show 29-45% HTTP/3 adoption versus <7% for origins

- Security Excellence: 95.6% of CDN traffic uses TLS 1.3, compared to 77.7% for origin servers

- Compression Innovation: Leaders like Automattic achieve 97.5% Brotli adoption, with Zstandard growing from 3% to 12% year-over-year

- Performance Advantages: CDNs deliver DNS responses 19% faster on mobile and 60% faster on desktop

This year we took a deeper look at HTTP/3 and revisited Early Hints, which we first examined in 2024. For the first time, we broke out CDN performance and security and will dive deeper in 2026, specifically on trade-offs that exist between both topics. We initially planned to include IPv6 analysis, but the data wasn’t reliable enough to draw meaningful conclusions. We hope to address IPv6 adoption in the 2026 chapter once we have more robust measurements.

The CDN landscape in 2025 demonstrates that these platforms have evolved far beyond simple content delivery to become comprehensive optimization and security platforms that are essential infrastructure for the modern web.

We recommend readers visit the Security chapter of the 2025 Web Almanac where several topics in this chapter are expanded on and provide data through a different lens.

Join us again in 2026 as we collect and analyze more data to see what new insights we can share with our readers.