Privacy

Introduction

The web is the primary interface for digital services, making it a significant source of data as billions of users interact with these systems daily. Consequently, website tracking – the practice of collecting data about visitors – has become a fundamental component of the modern web ecosystem. The motivations for this data collection vary widely, ranging from improving application performance and functionality to enabling targeted advertising and marketing analytics.

However, the scale of this data collection raises significant privacy concerns, making it a widely discussed topic in technical and political spheres, and a major area of ongoing research. While developers utilize various technologies to track users, such as HTTP cookies and browser fingerprinting, there is a corresponding rise in privacy measures. These include browser-based restrictions, regulatory compliance tools, and privacy-enhancing extensions.

In this chapter, we provide a technical overview of the state of web privacy. We analyze the adoption of common tracking mechanisms and examine the prevalence of measures designed to prevent tracking, offering a data-driven look at the current landscape of user data collection.

Online tracking

Our analysis uses the WhoTracks.Me catalog of popular third-party trackers to identify the trackers present on the webpages. To be conservative in our analysis, we only count the WhoTracksMe categories advertising, pornvertising, site_analytics and social_media as trackers. This method allows us to determine the distinct third-party trackers at the domain level for each webpage. It is worth noting that the reported numbers represent unique domains, not the total number of HTTP requests.

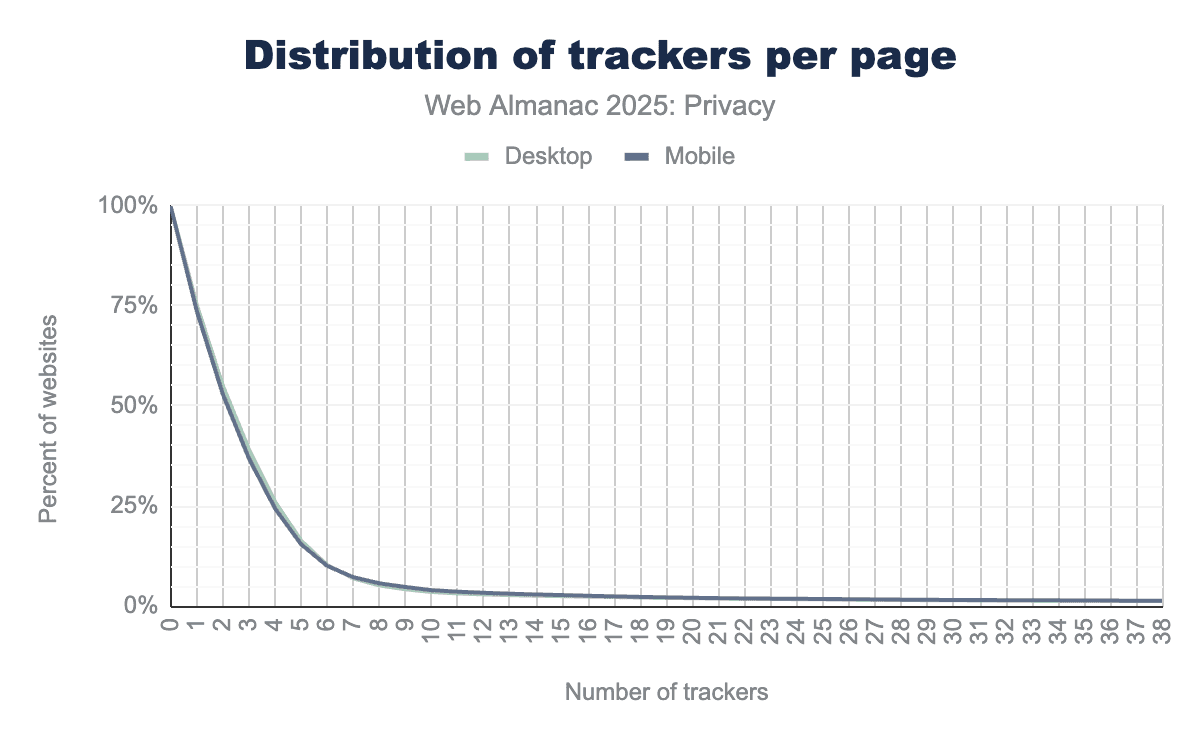

We see at least one third-party tracker in 75% of all webpages (75%: desktop, 74%: mobile), 55% of desktop webpages contain 2 and 39% contain 3 trackers. Up to 6 trackers setup happens more often in desktop pages, while 7 and more trackers are seen more often in mobile pages.

Stateful tracking

Tracking mechanisms are categorized as stateful or stateless. Stateful methods, such as cookies and local storage, store identifying information on the user device. In contrast, stateless methods, like fingerprinting, infer this information at runtime from unique characteristics.

Third-party tracking services

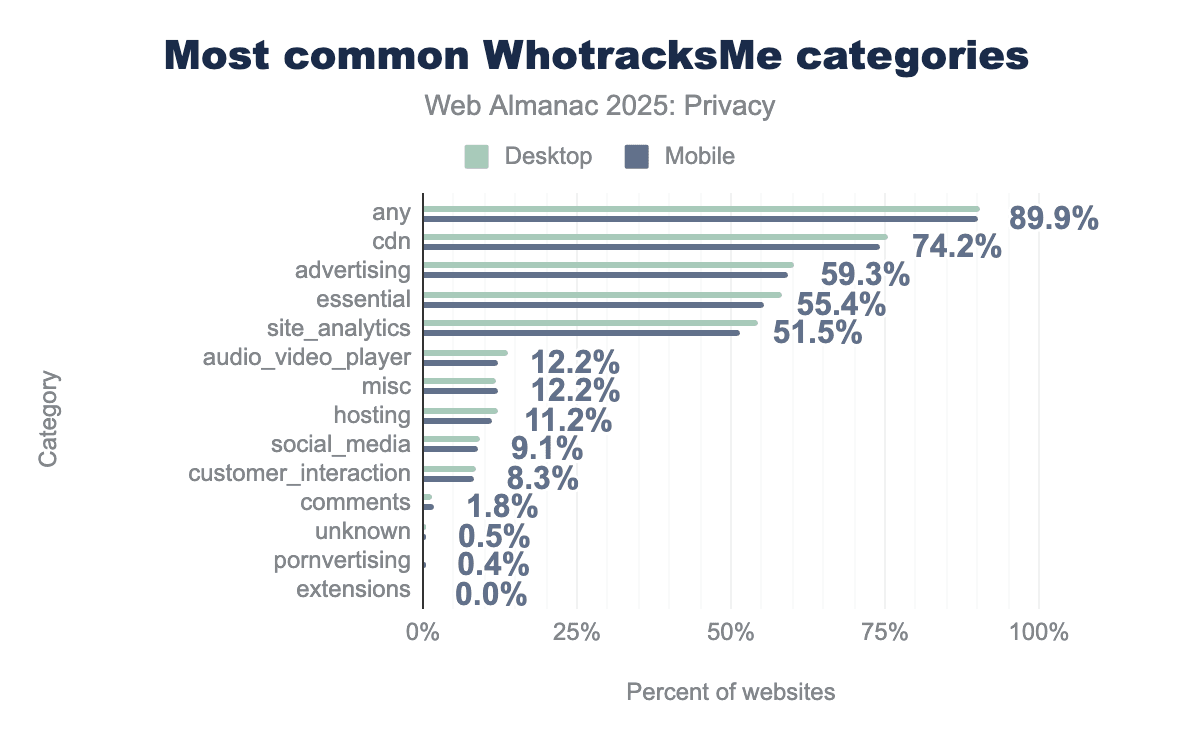

Here, we consider all categories of WhoTracksMe. We observe that most webpages connect to domains categorized as Content Delivery Networks (CDNs) and advertising. At least one CDN-related domain is present on 74% of webpages, followed by advertising-related domains on 59%. Additionally, 55% of webpages include essential domains (such as Google Tag Manager) and 52% contain analytics domains (such as Google Analytics). This high concentration among a few key players effectively sets a baseline for web privacy, where the vast majority of user data flows through a small number of dominant platforms.

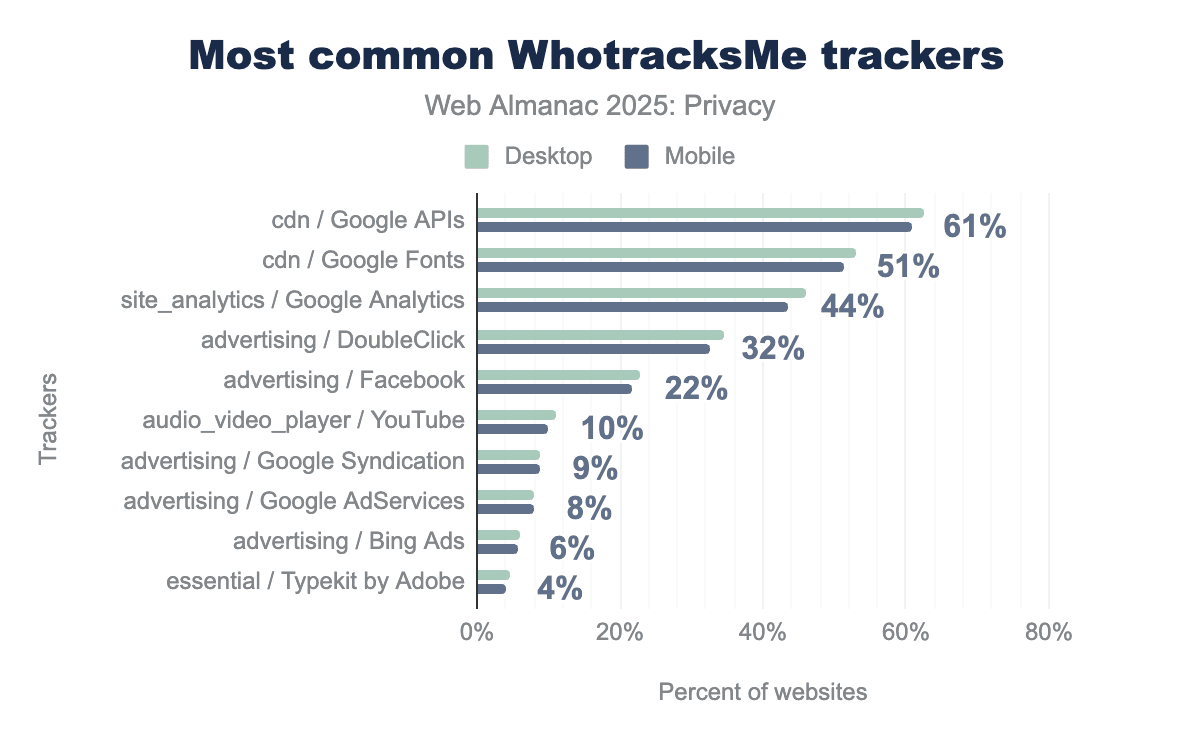

Our analysis of single trackers shows that Google and Facebook are the majority of tracking services. These entities are the most prominent trackers on the Web, with Google present on 61% of webpages and Facebook on at least 22% of webpages. They are followed by Bing (6%) and Adobe (4%).

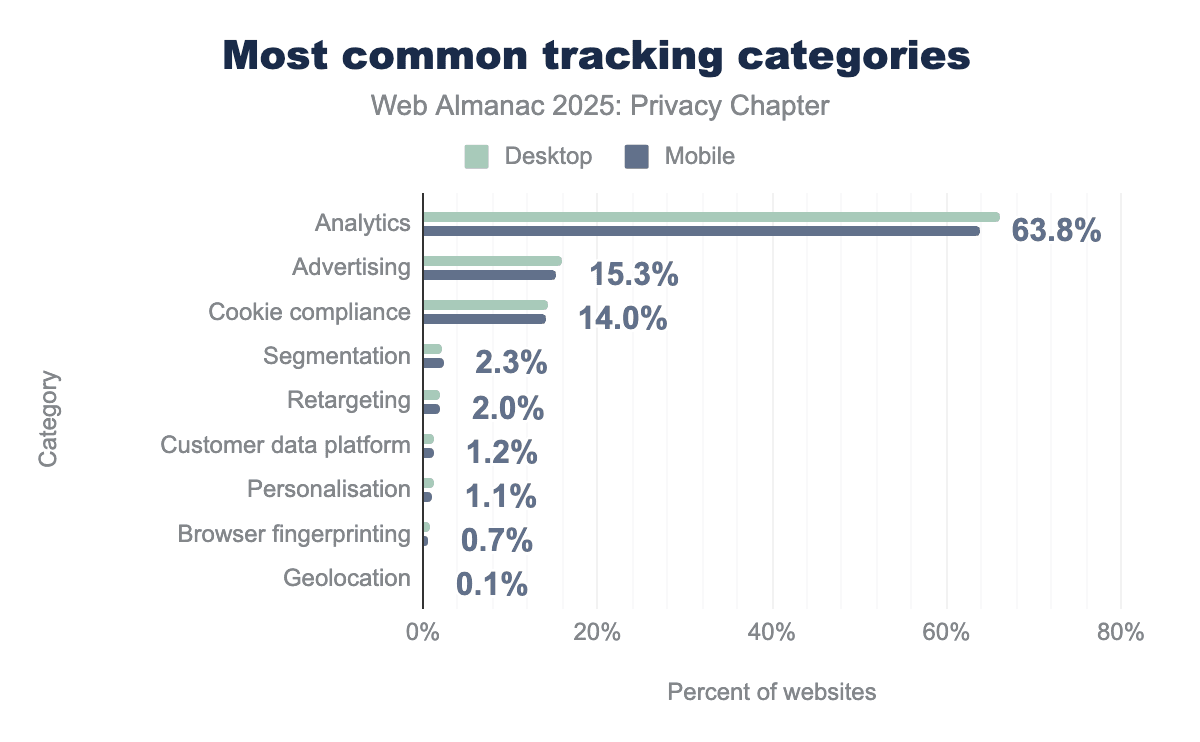

Furthermore, when categorizing these services by function, Analytics dominates the landscape, appearing on 64% of desktop webpages. Advertising and Cookie compliance tools follow at 15% and 14% respectively, illustrating that performance monitoring remains the primary driver of data collection. More specialized tracking methods, such as Segmentation and Retargeting, are significantly less common, each found on fewer than 3% of sites.

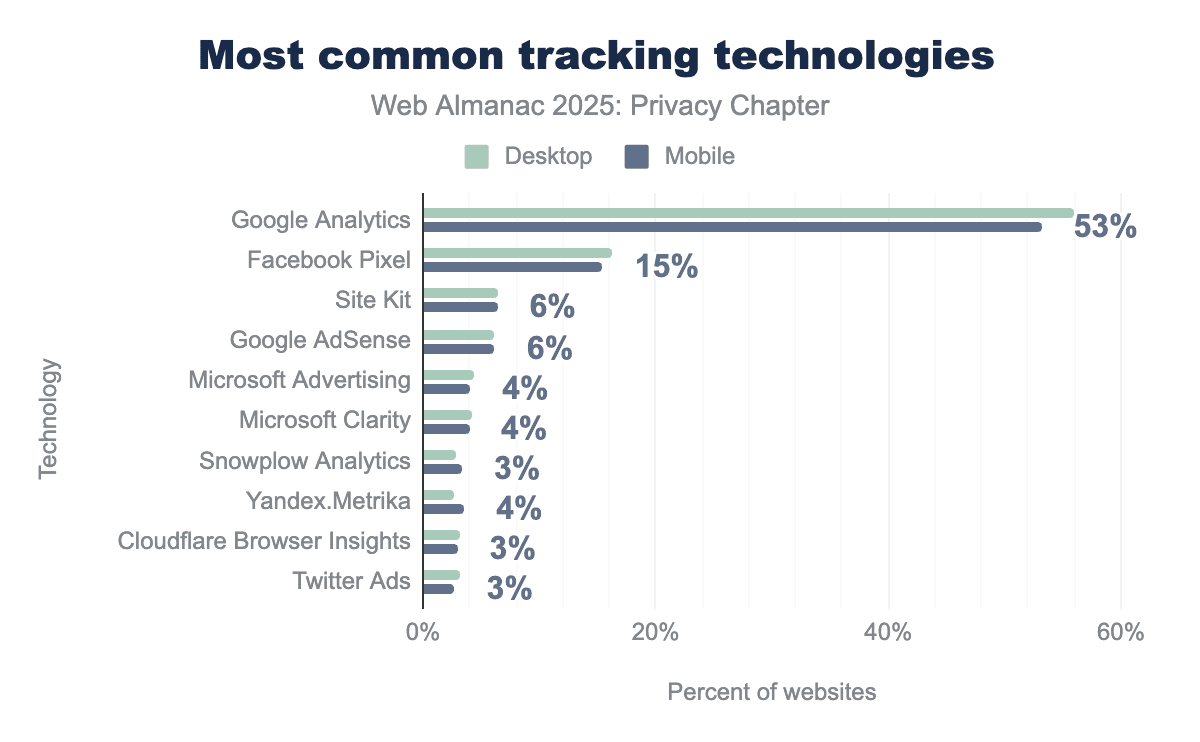

Tracking can happen in different contexts – from understanding user behavior on webpages to building complex advertising profiles. We find that Google Analytics (53%) and Facebook Pixel (16%) are the most popular technologies used to track web users. Beyond these market leaders, adoption drops significantly, with Google’s Site Kit (6.41%) and AdSense (6.18%) representing the next tier of usage. Other players like Microsoft also maintain a consistent but smaller footprint, with their Advertising and Clarity tools each present on approximately 4% of websites.

Third-party cookies

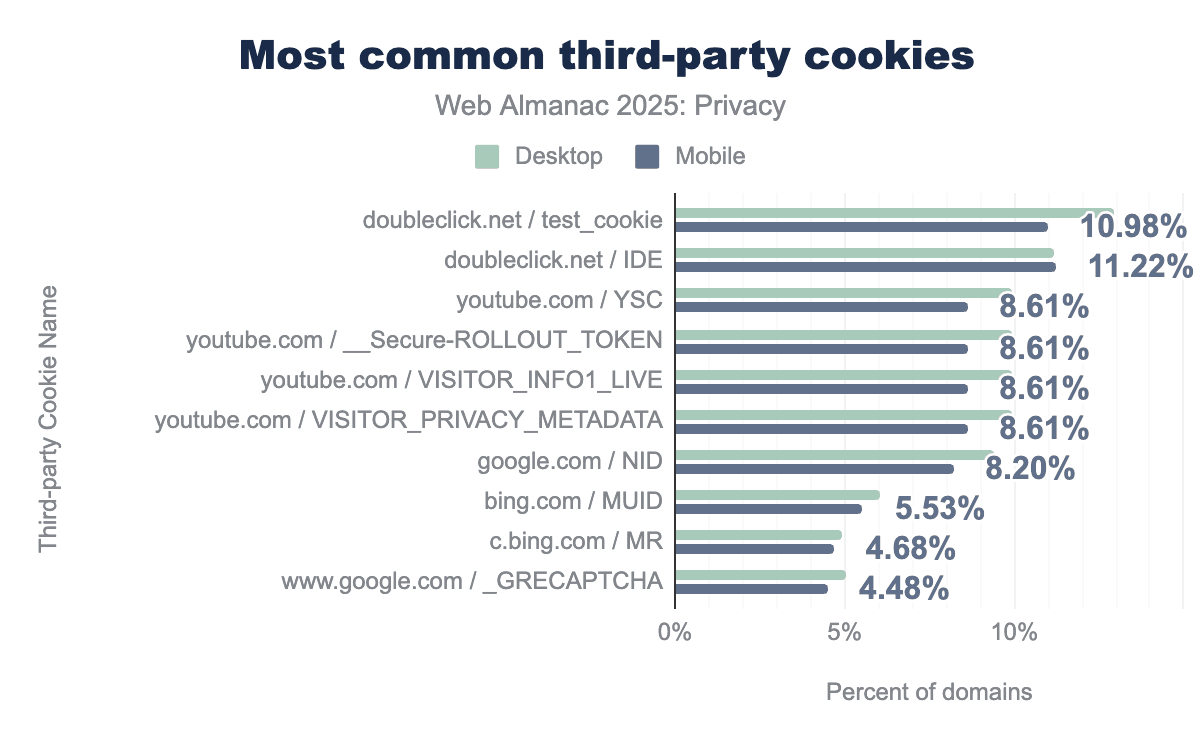

Using third-party cookies is an efficient method for tracking and targeting web users. Third parties utilize cookies for user tracking. Despite consistent criticism, this remains a common technique on the web. Although some vendors, like Google, have announced plans to phase out third-party cookies (and later reconsidered), they remain a significant technique for tracking and the majority of the third-party cookies used for tracking purposes.

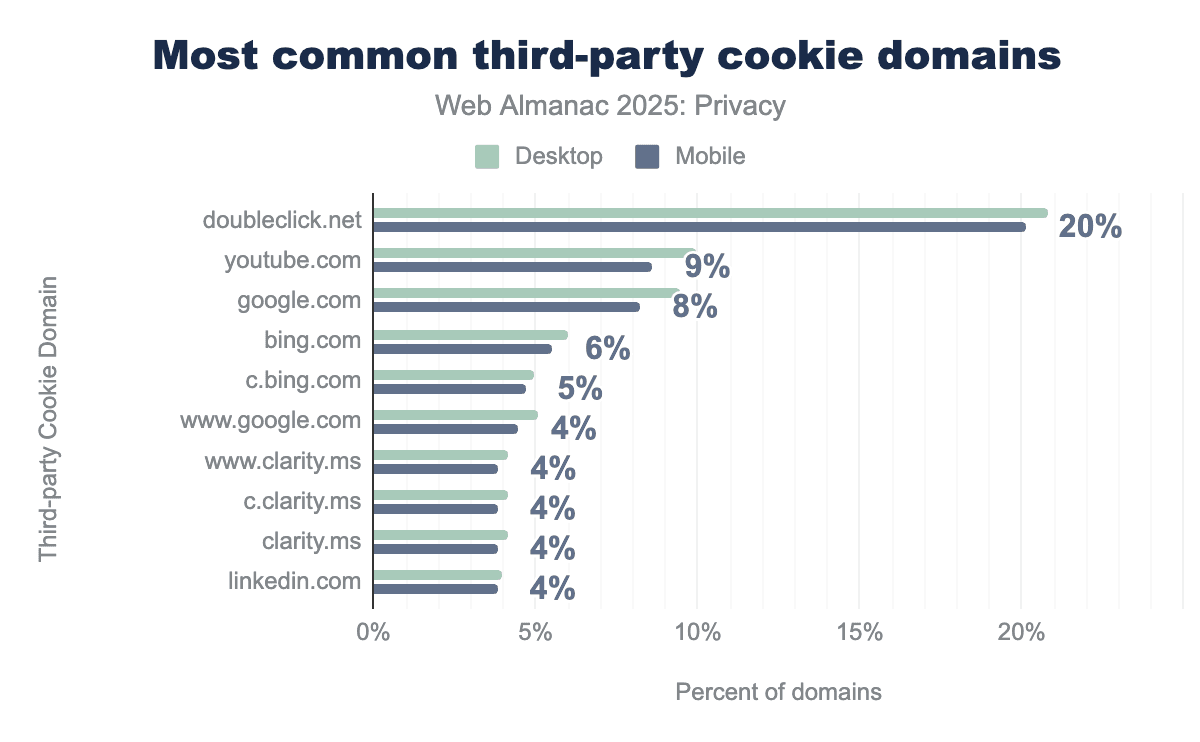

Our analysis shows that doubleclick.net is the most common third-party cookie domain, appearing on 20% of desktop sites, followed by youtube.com (9%) and google.com (8%). Overall, while Google entities dominate the top rankings, Microsoft’s bing.com and clarity.ms, along with linkedin.com, represent the most significant alternative third-party cookie setters.

First-party cookies

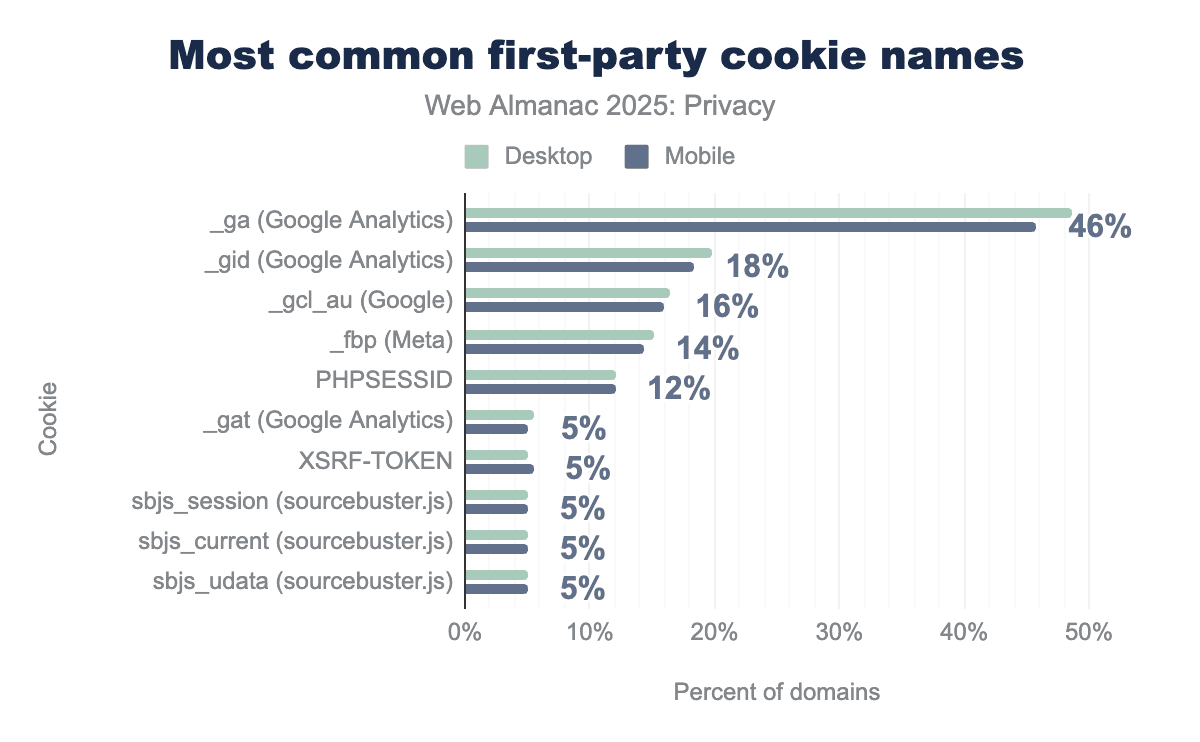

The following figure shows the most common first-party cookies. While these cookies are set in a first-party context, their names provide evidence that they are primarily used for tracking purposes. The _ga cookie is set on 46% of webpages, and _gid appears on 18%, both used by Google Analytics, followed by gcl_au on 16% of webpages. While the exact purpose of these cookies was not tested, Google publishes their intended functions. Another popular first-party cookie is _fbp, used by Meta on 14% of webpages. Meta provides advertisers the option to use first-party cookies with the Meta Pixel. Similar to the results observed for third-party context, Google and Meta remain the dominant entities for tracking in the first-party cookie context.

The usage of cookies on the web remains largely for tracking purposes. Among the functional exceptions, PHPSESSID stores a unique session ID for PHP applications on 12% of pages, while XSRF-TOKEN handles security against cross-site request forgery and is found on 6% of webpages.

PHPSESSID (12%).The Cookies chapter further describes the details and usage trends of cookies extensively.

Stateless tracking

Stateless tracking is the process by which user identifiers are generated on the fly, rather than stored in the browser as state. These identifiers are generally created by using information that can be actively or passively gathered from the target user’s device or browser. While it is tricky to correlate the sessions of a user who uses multiple devices, it is effective in that some signals are inherent to the device or website functionality and cannot be easily ’blocked’.

Browser fingerprinting

Browser fingerprinting is a method by which websites can identify a user based on their specific browser information. This information can include system fonts, language settings, hardware configurations, and other such seemingly innocuous datapoints that individually reveal little information, but can be put together to paint a unique picture of a specific user. They are commonly leaked through HTTP headers and JavaScript API calls.

Prior work has shown browser fingerprinting to be highly prevalent in online tracking. Its attractiveness can be attributed to the fact that it is difficult to block, and claims to be effective even if the user is using an Incognito browser. In this report, we identify the most common technologies used to do browser fingerprinting.

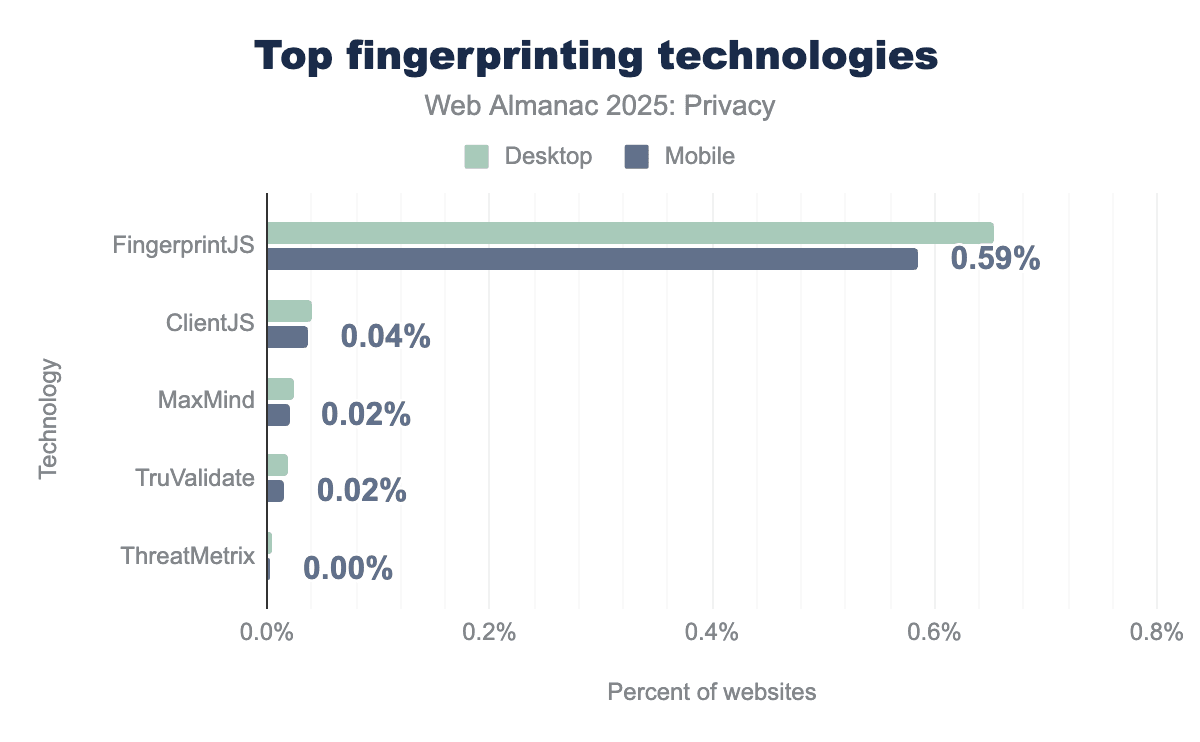

Of note, the library FingerprintJS has remained the most popular tool to conduct browser fingerprinting, far surpassing the others. FingerprintJS is used on 0.59% of mobile accessed websites, compared to ClientJS (the next most popular technology) which is present on 0.04%.

The popularity of FingerprintJS can likely be attributed to its thriving open source community, which appears to be more active than that of ClientJS.

Evading tracking protections

As browsers and privacy tools have become more effective at blocking third-party trackers, the tracking industry has adapted. Techniques like CNAME cloaking and bounce tracking allow trackers to disguise themselves as first-party resources or use intermediate redirects to circumvent traditional blocking methods. These approaches exploit the trust browsers place in first-party requests, making them harder to detect and block. In this section, we focus on bounce tracking, which can be observed through redirect chains in our crawl data.

Bounce tracking

Bounce tracking is a technique where users are briefly redirected through an intermediate domain before reaching their destination. During this redirect, often imperceptible to the user, the intermediate site can set or read cookies, effectively tracking users across sites while appearing as a first party interaction. This sidesteps traditional third-party cookie blocking.

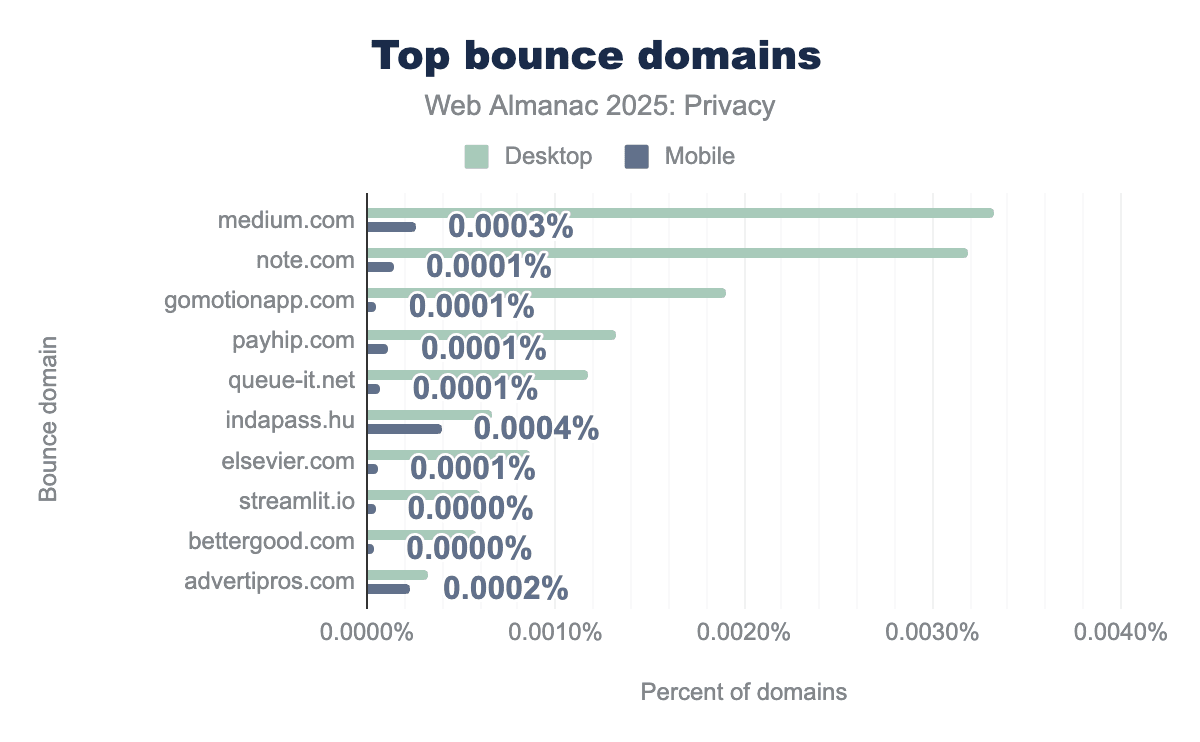

indapass.hu and medium.com are observed on fewer than 0.001% of domains, reflecting low prevalence or effective browser mitigations.medium.com remains the most common bounce domain in the 2025 dataset at 0.0003%, followed by note.com and indapass.hu. Year-over-year, prevalence dropped significantly; for instance, medium.com fell from 0.009% to 0.0003%, and indapass.hu from 0.012% to 0.0004%. This decline likely reflects Chrome’s bounce tracking mitigations taking effect. Because the top domains (queue-it.net, payhip.com, medium.com) are legitimate functional services, the data suggests most observed behavior stems from necessary redirects rather than covert tracking.

Browser policies to improve privacy

Browsers have introduced various mechanisms that can influence how much information websites share with third parties. These features operate at the protocol level, controlling headers, limiting data exposure, and standardizing how sites communicate with external resources. Their actual privacy impact depends on implementation, adoption, and whether sites choose to use them.

In this section, we examine three such mechanisms: User-Agent Client Hints, which offer a more controlled alternative to the traditional User-Agent string; Referrer policy, which lets sites limit how much navigation context is passed to third parties; and privacy-related Origin Trials, where browsers experiment with new features before wider rollout.

User-Agent Client Hints

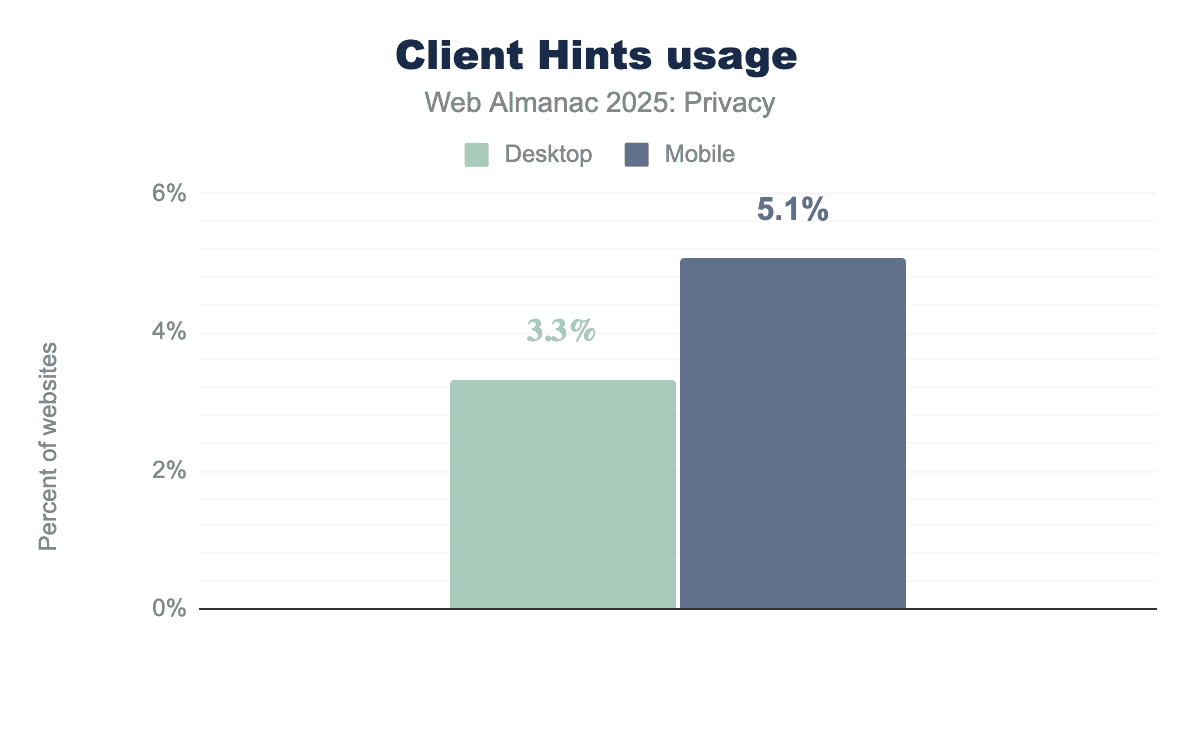

User-Agent Client Hints offer a privacy-conscious alternative to the traditional User-Agent string, allowing browsers to share device and browser information only when explicitly requested by servers. Instead of exposing a detailed fingerprint by default, sites must opt in to specific hints, reducing passive data leakage. In 2025, adoption sits at 3.3% for desktop and 5.1% for mobile, with mobile’s higher rate likely reflecting greater need for responsive design signals. This transition is now permanent; with Chrome 145 removing the UserAgentReduction policy, sites must migrate to User-Agent Client Hints for detailed browser or device information.

Last year’s data showed a strong correlation between site popularity and Client Hints usage; the top 1,000 sites reached 15.85%, while adoption dropped sharply to around 1.6% at the 100,000 tier. While this year’s methodology doesn’t break down by rank, the overall figures suggest adoption remains concentrated among larger sites, with the long tail yet to embrace the standard.

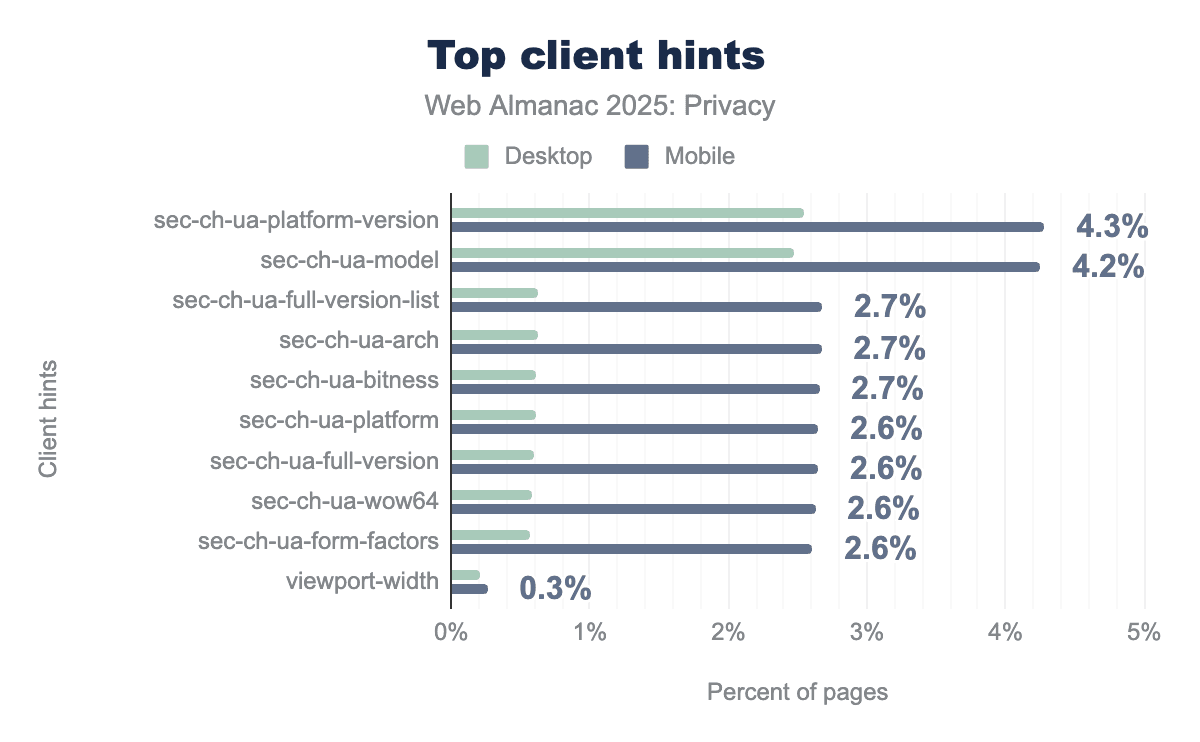

The most requested Client Hint is sec-ch-ua-platform-version at 4.28%, used to detect OS version for compatibility decisions. Close behind is sec-ch-ua-model at 4.25%, though with a notable skew: mobile usage far exceeds desktop, which makes sense given that device model is primarily relevant for mobile experiences and debugging. The remaining hints, covering architecture, bitness, full version lists, and form factors, cluster tightly between 2.60% and 2.67%, suggesting that sites requesting Client Hints tend to request several together rather than cherry-picking individual signals.

Referrer Policy

When you click a link from one website to another, your browser can reveal where you came from, including the full page URL. Referrer Policy gives website owners control over how much of this information is shared, helping protect user privacy by limiting what third parties can see about your browsing path.

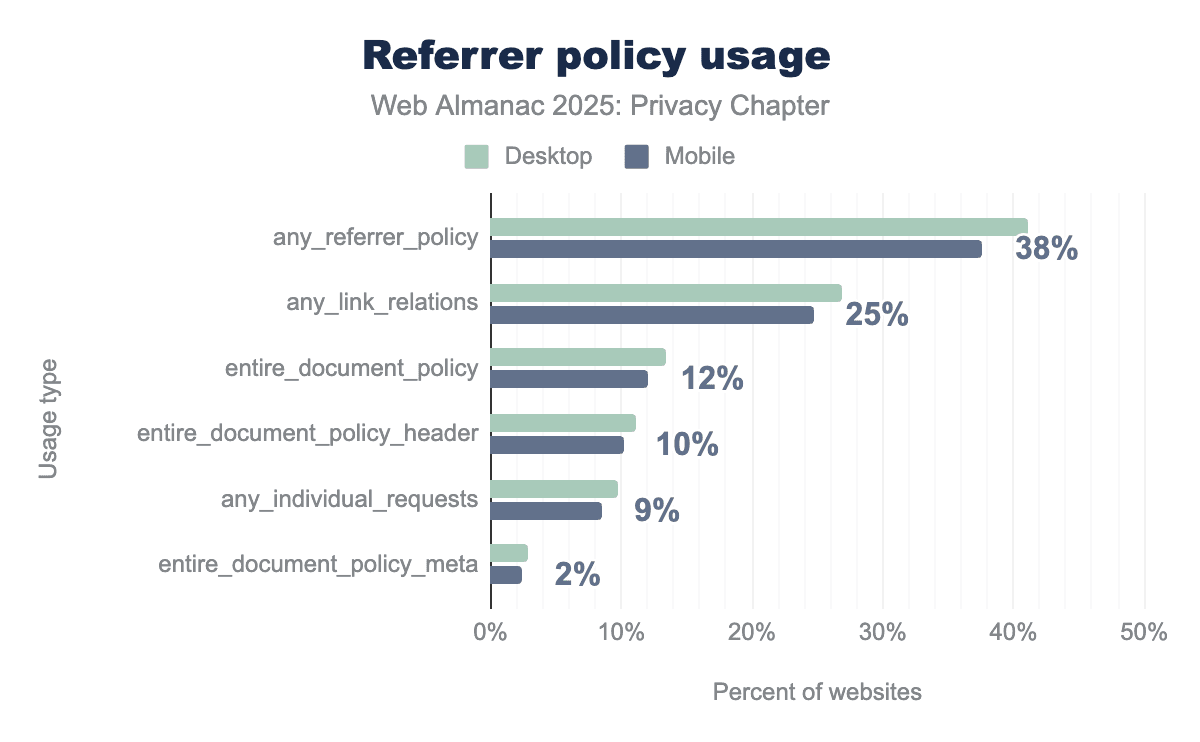

Overall adoption of Referrer Policy rose from 32% in 2024 to 37.66% in 2025, a healthy increase. The most common implementation method remains link-level controls (like rel="noreferrer" on individual links) at 24.70%, while document-wide policies set via headers sit at 10.16%. This suggests many sites apply referrer restrictions selectively rather than as a blanket rule.

Meta tag implementations remain the least common at 2.47%, largely unchanged from 2024’s 2%. This is expected; headers are generally preferred for security policies since they’re harder to tamper with and apply before the page loads.

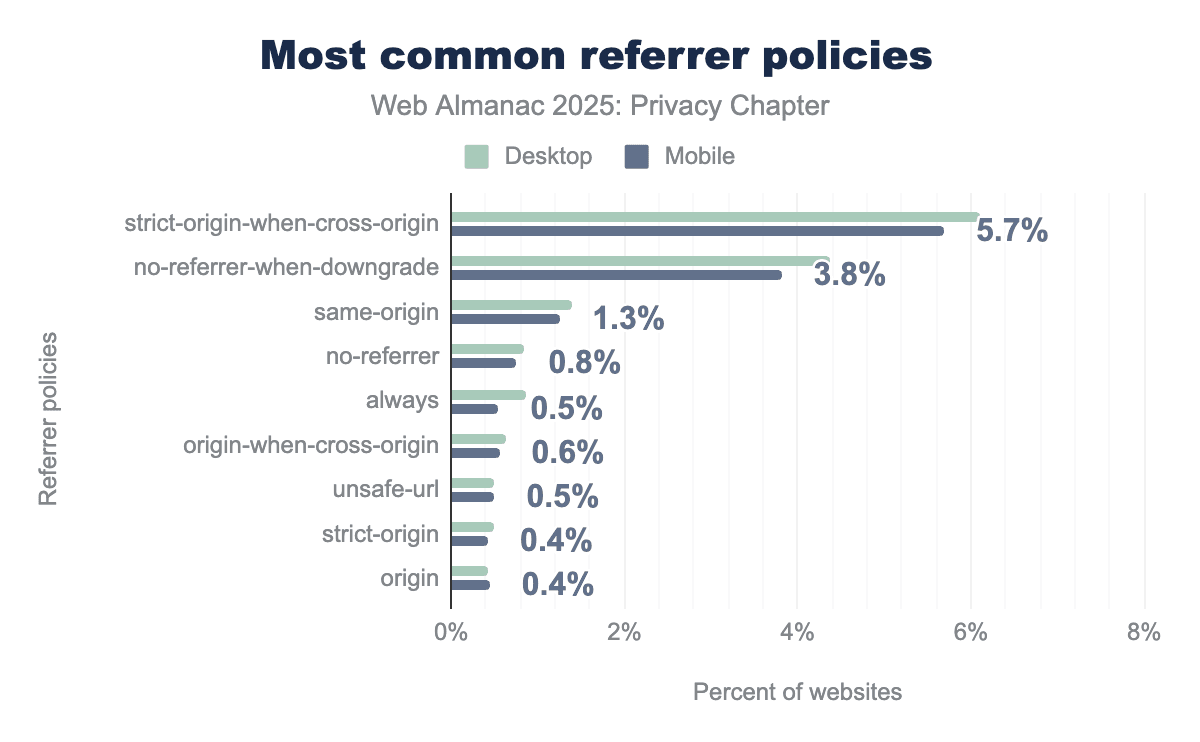

The most privacy-conscious policies saw a decline this year, strict-origin-when-cross-origin, which shares the origin but strips the full path when navigating to other sites, dropped from 7.5% to 5.69%. Similarly, no-referrer-when-downgrade fell from 7.0% to 3.81%. These remain the top two policies, but the decrease suggests some sites may have relaxed their settings or shifted implementations.

On the positive side, truly restrictive options like same-origin (1.26%) and no-referrer (0.75%) remain in use, though adoption is low. These policies share nothing with third-party sites, ideal for privacy, but sometimes limiting for analytics and affiliate tracking that sites rely on.

Some sites still specify unsafe-url (0.50%), which exposes the full URL to any destination, though this behavior is Chrome-specific and other browsers have deprecated it. We also see always (0.54%), an invalid value that browsers ignore and fall back to the default strict-origin-when-cross-origin. The presence of these values suggests some sites have misconfigured or outdated referrer policies rather than intentionally choosing privacy-unfriendly settings.

Privacy-related origins trials

Origin trials let browsers test experimental features on real websites before committing to a full rollout. Sites can opt in to access new capabilities early, or opt into deprecation trials to temporarily delay changes that would break existing functionality. These trials help browser vendors gather data on how features perform in production while giving developers time to adapt, and as we’ll see, most privacy-related adoption falls into the deprecation category.

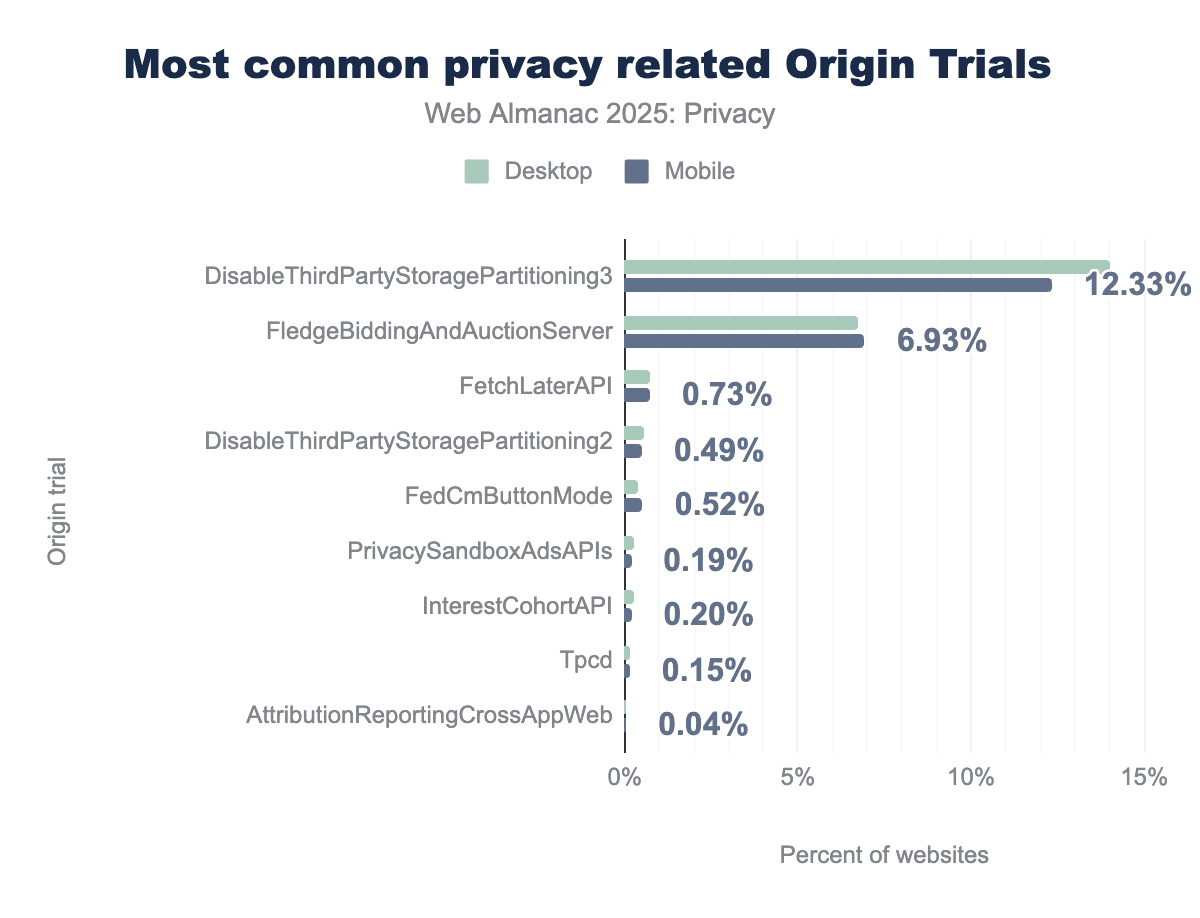

The most widely adopted trial remains DisableThirdPartyStoragePartitioning, which increased from 10.21% in 2024 to 12.33% in 2025 (now in its third iteration). This trial allows sites to temporarily opt out of storage partitioning, a privacy feature that isolates cookies and storage per site, giving developers more time to migrate legacy implementations. Similarly, FledgeBiddingAndAuctionServer, part of Google’s Privacy Sandbox initiative for interest-based advertising without cross-site tracking, grew modestly from 6.62% to 6.93%.

The biggest shift is AttributionReportingCrossAppWeb, which dropped sharply from 2.10% to just 0.04%. This suggests either the trial ended or sites moved away from testing cross-app attribution. New entries include FetchLaterAPI (0.73%), deferred requests, and federated identity. Meanwhile, InterestCohortAPI, the controversial FLoC predecessor, lingers at 0.20%, largely unchanged and likely residual.

Law and policy

Privacy regulations continue to shape how websites interact with users. In this section, we examine how sites are responding through consent dialogues, and whether privacy signals like Do Not Track and Global Privacy Control are gaining meaningful adoption.

Consent dialogs

Privacy regulations like GDPR and CCPA require websites to obtain user consent before collecting and processing personal data. This has made cookie consent dialogs often managed by Consent Management Platforms (CMPs) a near-universal feature of the modern web. To standardize how consent is captured and communicated across the advertising ecosystem, the Interactive Advertising Bureau developed frameworks like the Transparency and Consent Framework (TCF), US Privacy String (USP), and the newer Global Privacy Platform (GPP).

While these frameworks aim to give users control, adoption and implementation quality vary widely. Some sites fully comply with TCFv2, while others have incomplete implementations or rely on older standards. It’s also worth noting that our crawler is US-based and under TCF, consent banners aren’t required for non-EU visitors, so actual TCF usage is likely higher than what we measure here.

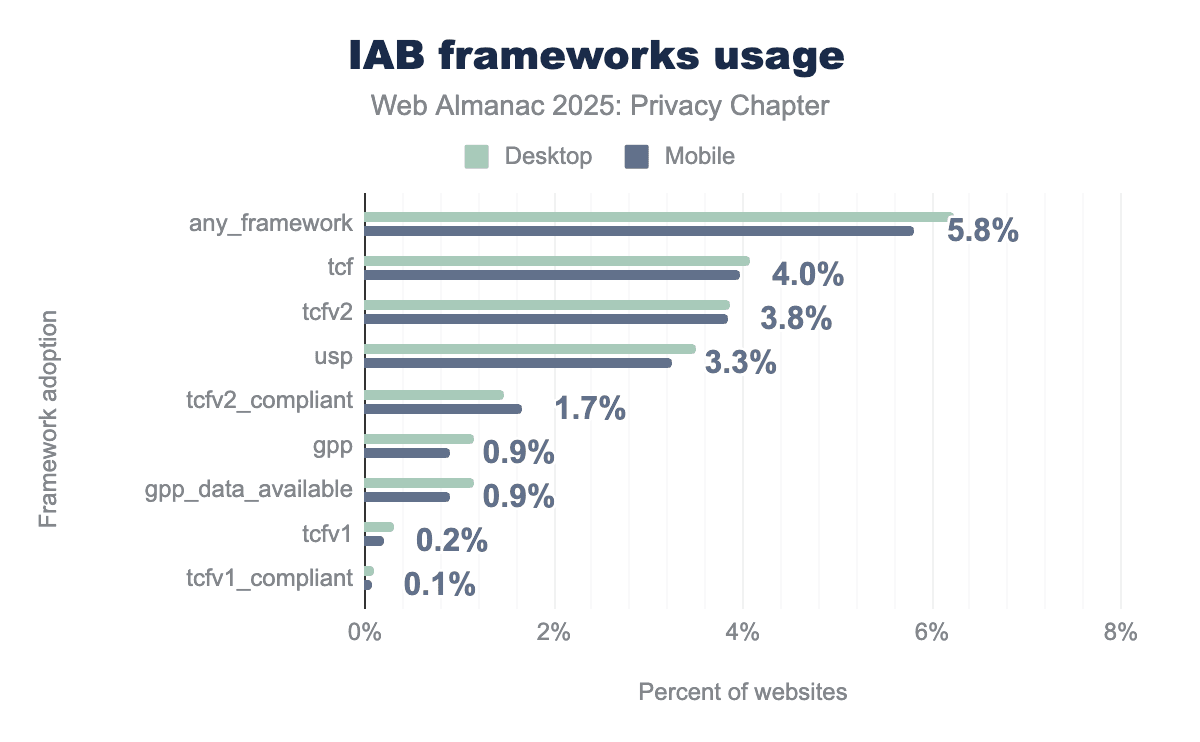

Overall IAB framework adoption remains steady at just above 5.5% for both mobile and desktop. TCF continues to be the most widely adopted framework at 4.0% with TCFv2 accounting for 3.8%. However, only 1.7% of sites are fully TCFv2 compliant, less than half of those claiming to use TCFv2, suggesting that many implementations remain incomplete or improperly configured. USP holds steady at 3.3%, reflecting continued CCPA compliance efforts.

The deprecated TCFv1 has nearly disappeared, sitting at just 0.2% with only 0.1% compliant, indicating the industry has potentially migrated to v2. A notable addition this year is GPP, the IAB’s newer unified framework, which appears on 0.9% of sites. Encouragingly, gpp_data_available matches at 0.9%, meaning sites that have adopted GPP are actually using it to transmit user preferences rather than just loading the code.

Comparing year over year, overall framework adoption held flat while TCF usage dipped slightly from 4.2% to 4.0%. This modest decline may reflect early migration toward GPP, though it’s too soon to call it a trend. The compliance gap persists, and TCFv2 compliance remained unchanged at 1.7%, highlighting that adoption alone doesn’t guarantee proper implementation.

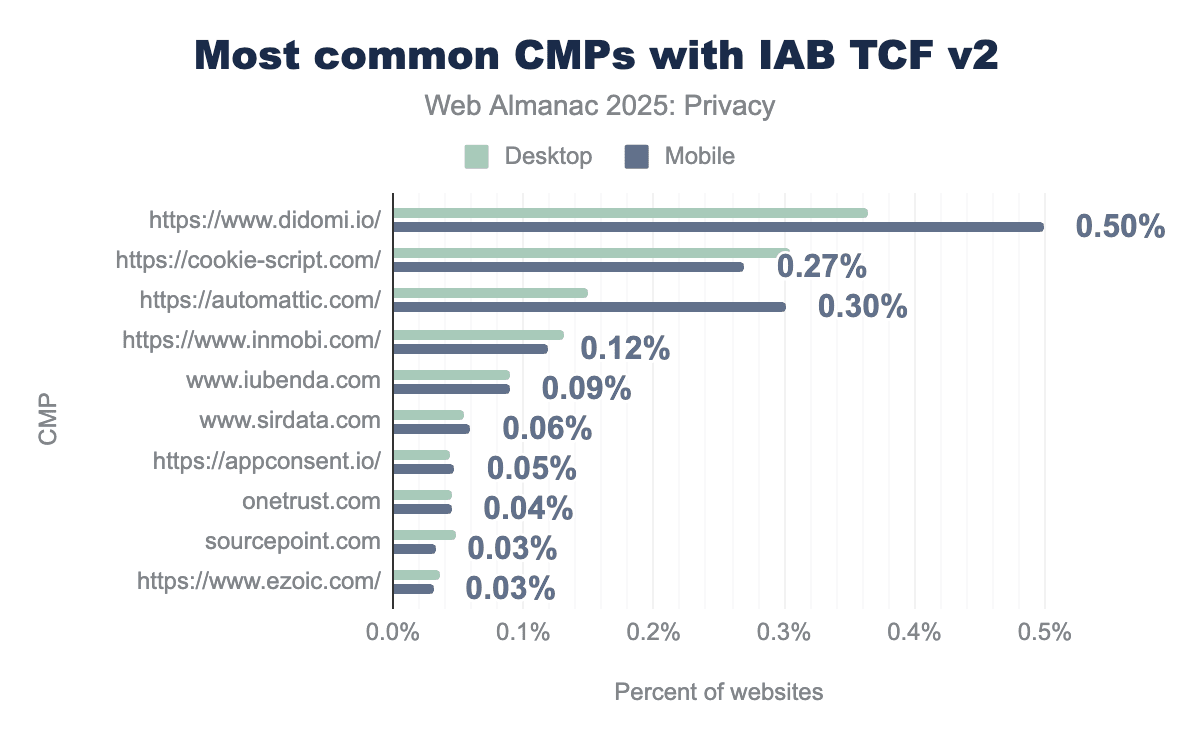

The CMP landscape shifted notably this year. Automattic, which led in 2024 at 0.67%, dropped to 0.30% in 2025, while Didomi climbed from 0.22% to 0.50%, taking the top spot. Cookie-script emerged as a new entrant at 0.27%, ranking second on desktop. The remaining providers, InMobi, Iubenda, Sirdata, AppConsent, OneTrust, Sourcepoint, and Ezoic, each account for less than 0.12% of sites, showing that TCFv2 CMP adoption remains concentrated among a few major players.

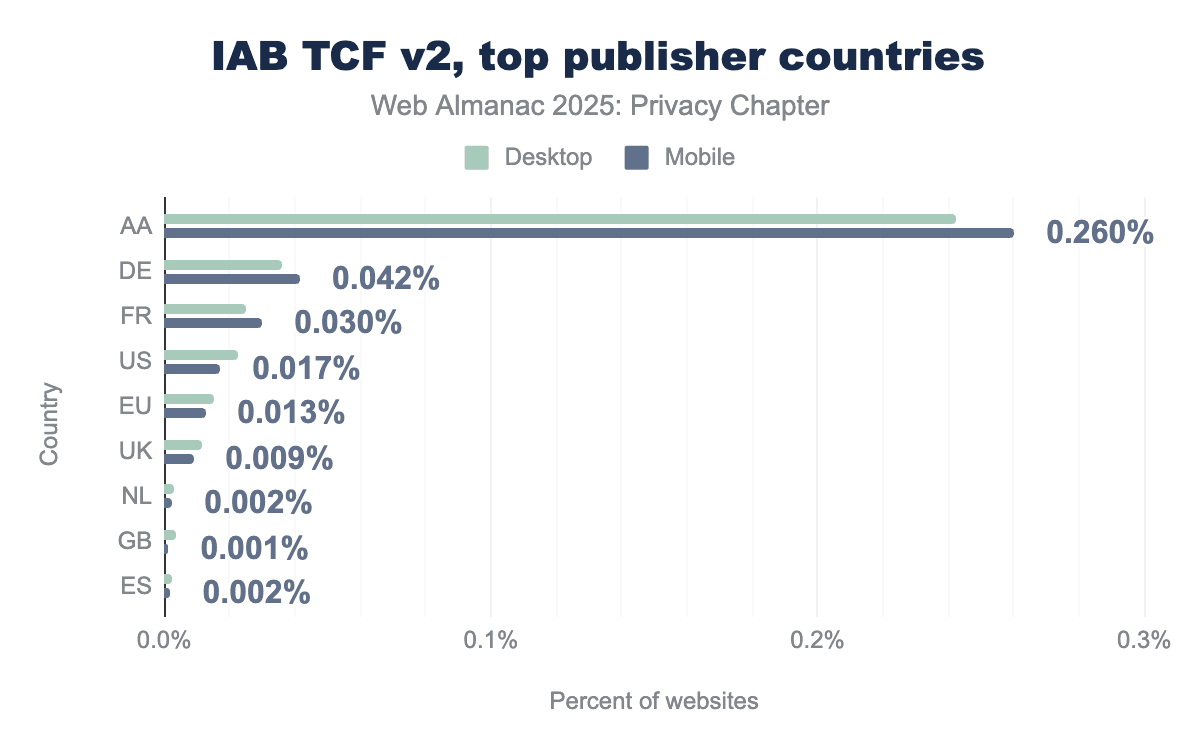

Germany (0.042%) and France (0.030%) lead TCFv2 publisher adoption among EU member states, with the US appearing at 0.017%, notable given TCF isn’t required outside the EU. The largest share (0.26%) falls under ’AA’, an undefined country code, pointing to gaps in publisher metadata or misconfigured CMP implementations. Overall adoption remains low even among European publishers, suggesting TCFv2 is concentrated among a small subset of sites despite GDPR requirements.

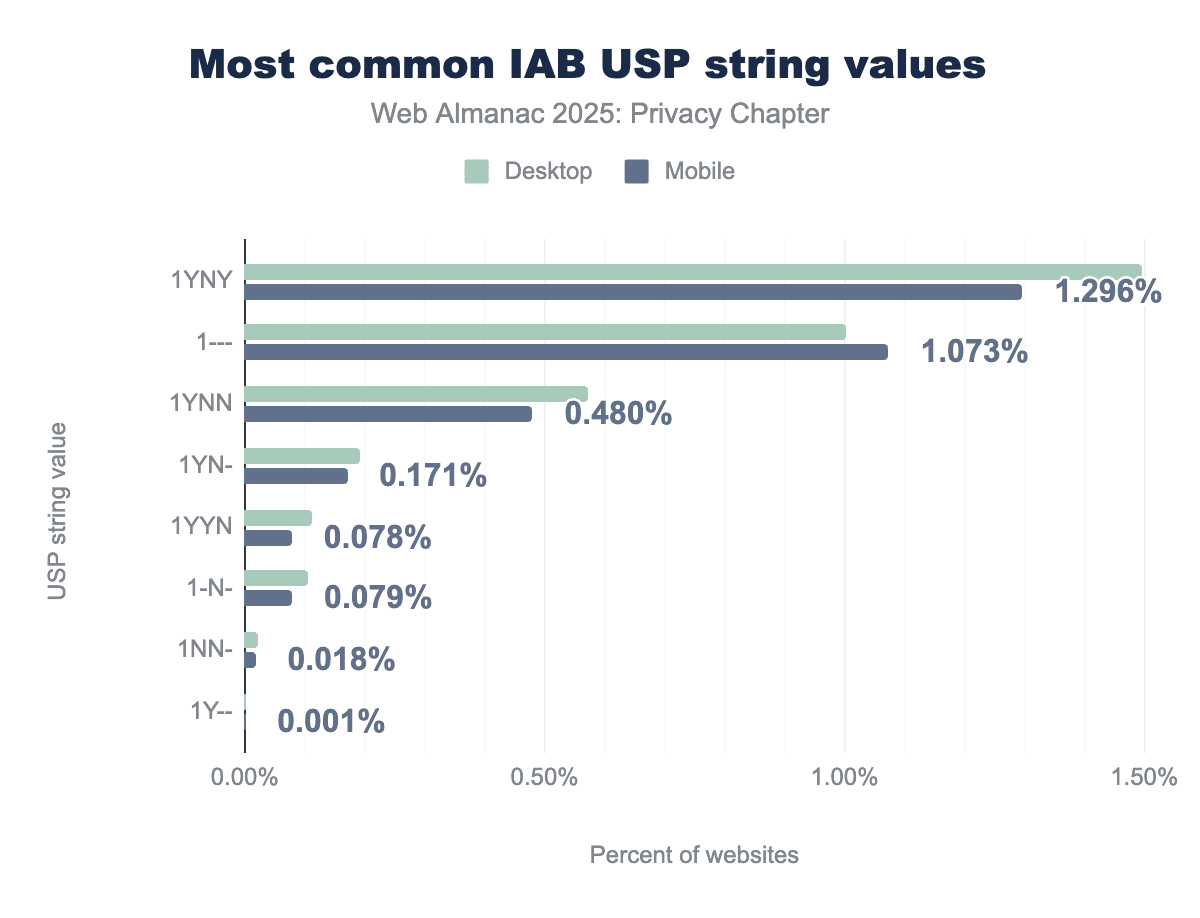

The most common USP string is 1YNY at 1.296%, indicating that notice was given, the user did not opt out, and the site is covered under the Limited Service Provider Agreement. The second most common value is 1--- at 1.073%, a placeholder string that provides no meaningful signal, suggesting many implementations are incomplete or default. We observed that sites showing 1YYN have configured their CMP to default new visitors to an opted-out state, a stricter-than-required privacy posture. The low prevalence (0.078%) indicates most sites follow CCPA’s standard opt-out model, where consent is assumed until explicitly revoked.

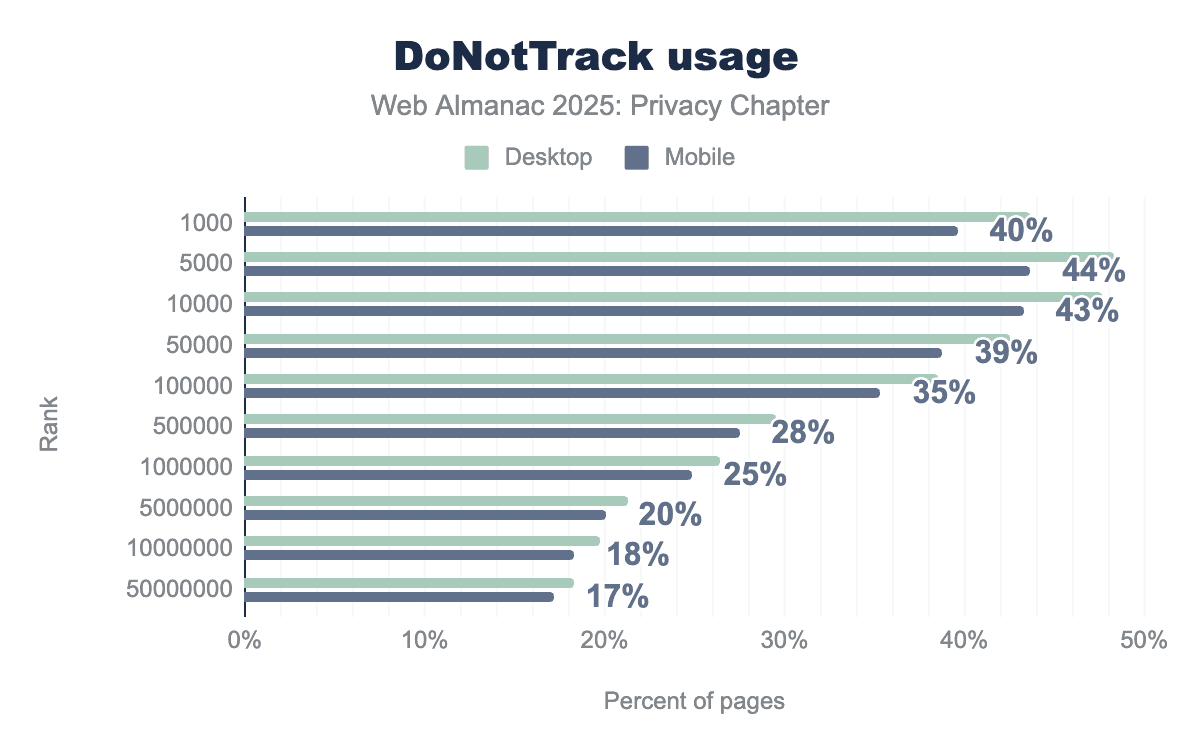

Do Not Track

Despite being largely abandoned as a standard, with minimum to no legal backing and most advertisers ignoring it, Do Not Track signals persist across the web. Interestingly, adoption correlates strongly with site popularity. Among the top 10,000 sites, DNT detection peaks at around 43%, while the long tail of sites are more likely to maintain legacy privacy signals, even if their practical impact remains questionable.

Mobile adoption consistently edges out desktop across all ranking tiers, though the gap is narrow. The steepest drop-off occurs between the top 100,000 sites (35%) and the 500,000 tier (27%), indicating that mid-tier and smaller sites are far less likely to check for DNT. Whether these sites actually honor the signal, rather than simply detecting it, remains an open question, as DNT compliance has never been enforceable.

Global Privacy Control

Global Privacy Control (GPC) is a browser signal that communicates a user’s preference to opt out of having their data sold or shared. Unlike Do Not Track, GPC has legal backing under CCPA/CPRA; websites must treat it as a valid opt-out request. Firefox, Brave, and Safari already support GPC, and Chrome is set to implement it in 2026 following California legislation requiring browsers to offer this setting by 2027. However, like DNT, GPC relies on websites to honor the signal voluntarily at a technical level; the browser sends the header (Sec-GPC: 1), but cannot enforce compliance. The difference is that ignoring GPC carries legal risk, which may prove more effective than DNT’s purely voluntary approach.

Conclusion

Online tracking has become the norm on today’s Internet. Indeed, we see that 75% (desktop) or 74% (mobile) of the websites we visited contained at least one tracker.

Google continues to dominate the tracking space, followed by Facebook. On the outset, online tracking is lucrative to large companies that can leverage it to serve more targeted ads. However, the consolidation of tracking information amongst a few centralized players is cause for concern to more privacy-conscious users.

Efforts to avoid tracking are constantly being deployed and evaded. For example, we observed medium.com in bounce sequences, though likely for functional purposes rather than covert tracking. However, we also discuss safer browser policies, such as sharing user-agent Client Hints instead of the actual user agent string.

Laws and regulations governing online tracking are evolving, along with the mechanisms deployed to comply with them. We see incomplete implementations and poor adoption of the latest version of TCF (v2). However, it comes with a rise in the adoption of the Global Privacy Platform, which is a new addition by the IAB. Moreover, we see a shift in the Consent Management Platform landscape.