Security

Introduction

While more and more parts of many people’s lives have moved online, so does their private data, which makes web security ever more important. Many systems we use on a daily basis remain appealing to attackers trying to steal data or cause disruptions. This year has once more demonstrated the scale and complexity of modern threats. The number of DDoS attacks have continued to increase in size and frequency, with the largest attack recorded reaching 31.4 Tbps in November. Supply chain vulnerability grew to unprecedented sizes, with the Shai-Hulud 2.0 attack reportedly compromising over 1,000 npm packages and infecting over 27,000 GitHub repositories. And a critical vulnerability in React known as React2Shell had developers working hard to quickly update their applications.

In this chapter, we analyze the mechanisms that aim to protect the web, and how in some cases they fail to protect the web due to a variety of reasons. We explore core elements of web security such as Transport Layer Security (TLS) and protections against third-party content inclusions. We discuss how the adoption of these security measures evolves, how they help prevent attacks and how misconfigurations can prevent their proper functioning. We further analyze some well-known URIs relating to security.

Beyond measuring adoption, we also explore the drivers behind the adoption of security mechanisms, such as location, technology stack and website industry. By comparing the results to data from previous editions of the Web Almanac, we can notice long-term trends and changes in the state of web security.

Transport security

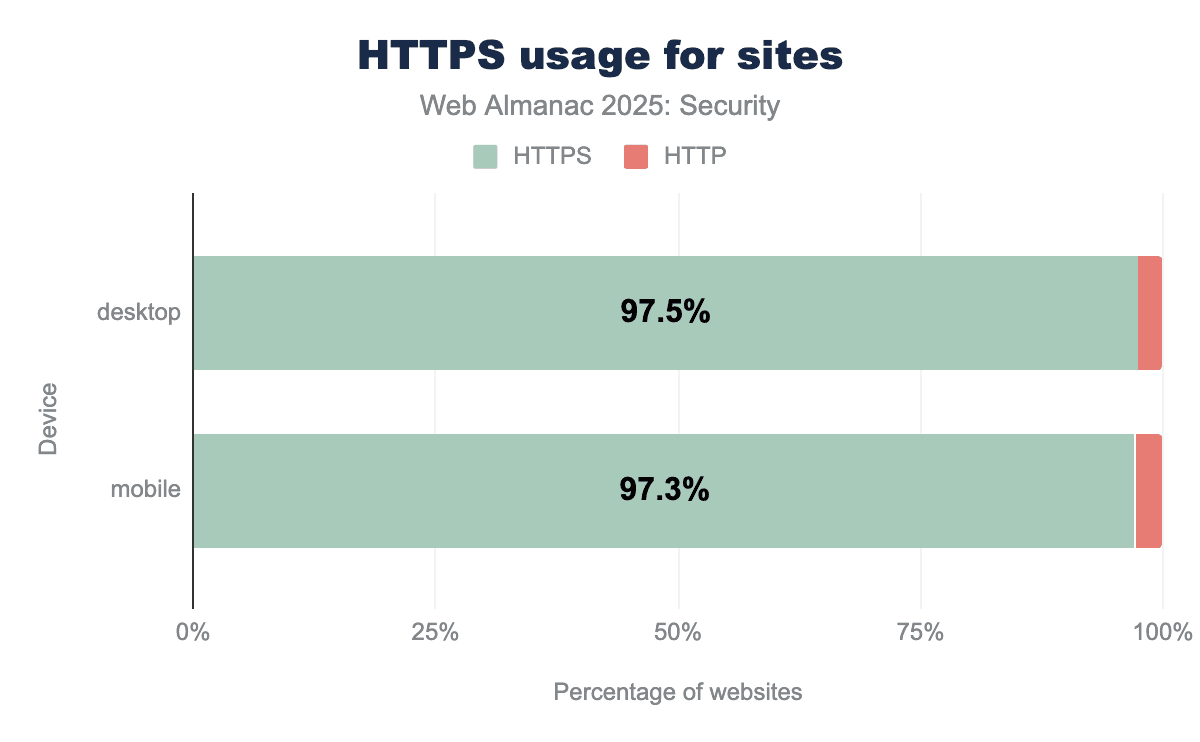

HTTPS uses Transport Layer Security (TLS) to secure the connection between client and server. Over the years, more and more websites started using HTTPS, thereby better securing their users. This year, the share of all requests sent over HTTPS rose again compared to last year, reaching over 98.8% for mobile connections.

The share of requests that are being sent using HTTPS rather than using plain HTTP creeps ever closer to 100%, rising by another 0.74% on mobile compared to the 2024 edition of Web Almanac.

Another positive evolution is visible in the number of homepages served over HTTPS. This number rises from 95.6% to 97.3% on mobile. Because many websites send a number of third-party requests to many (often secure) sites, this number tends to be lower than the share of requests sent over HTTPS, but luckily also keeps rising year after year.

It is good to see that the positive trends in these metrics continues and that the share of sites using HTTPS keeps closing in to 100%. Part of these high numbers can be explained by the decision of browser vendors (Chrome, Firefox and Safari) to try to communicate over HTTPS first before falling back to plain HTTP and often showing a security warning to users, thereby encouraging site owners to adopt TLS.

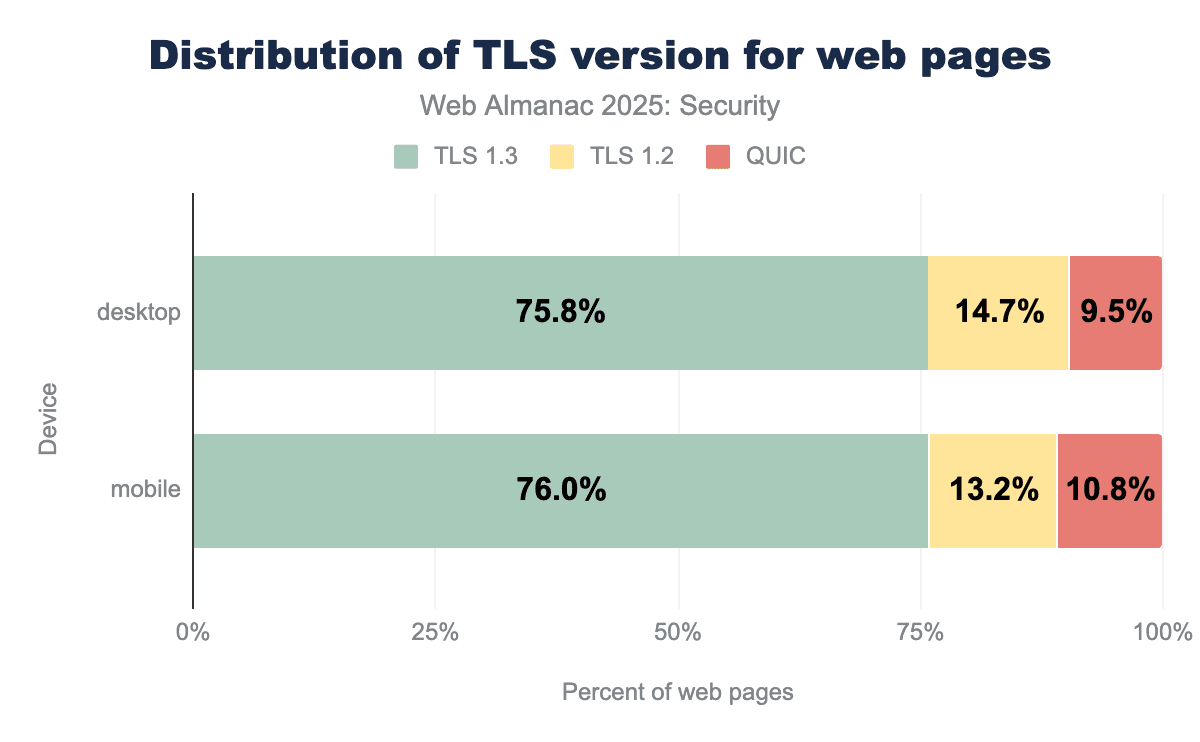

Protocol versions

For a few years now, TLS1.3 has been the recommended protocol version to have the highest security. The latest version has deprecated some algorithms that were found to contain flaws in TLS1.2 and provides some stronger security guarantees like forward secrecy. QUIC uses TLS internally as well, thereby providing similar security guarantees as TLS1.3 does.

Like in the 2024 edition of the Web Almanac, we find that both QUIC and TLS1.3 see an increase in use. Again we can assume that some sites using TLS1.2 have moved to TLS1.3 and some sites that were using TLS1.2 or TLS1.3 have moved to QUIC. TLS1.2 decreased by another 4.5% this year. We can see that the adoption of QUIC has slowed down a bit this year, with the share of sites using QUIC only rising by 0.8%. In the future, it can be expected that TLS1.2 will slowly phase out over (a long) time and QUIC will continue rising.

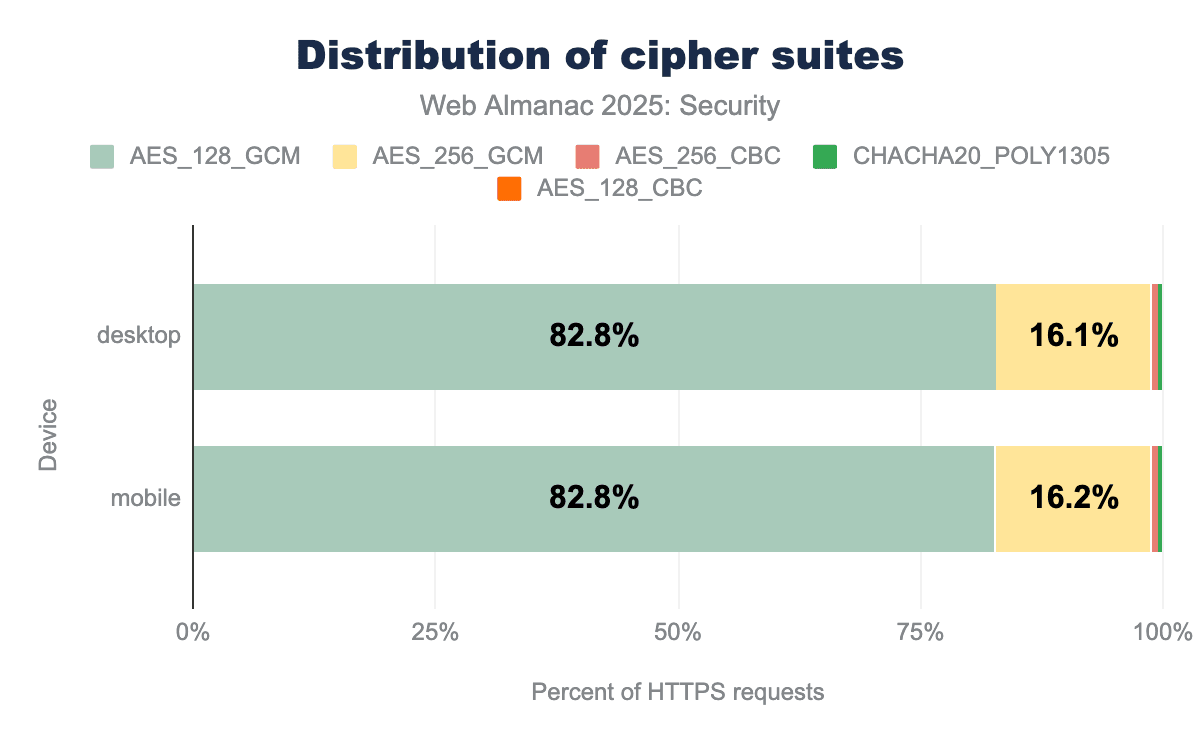

Cipher suites

To start communicating over an encrypted channel, both parties need to use the same cryptographic algorithm (or cipher suite) to understand each other. In order to do so, they agree upon a cipher suite to use before communication. We can see that most requests happen over a connection using a Galois Counter Mode (GCM) cipher, which is often preferred because of its resilience against padding attacks and because it provides Authenticated Encryption with Associated Data (AEAD), which is required in TLS1.3. In addition, we see that the use of 128-bit keys has grown by 4% since last year, instead of the more secure 256-variant. Although the 128-bit cipher suites are considered secure by NIST, 256-bit variants provide even more security guarantees. The dataset of this year’s Almanac includes more requests than last year’s, so it is possible that this change can be attributed to the growing dataset. The cipher suites in use are not very diverse, in fact there are only five cipher suites that were found to be used in the dataset. This can be the case because TLS1.3 only allows GCM or modern block ciphers to be used.

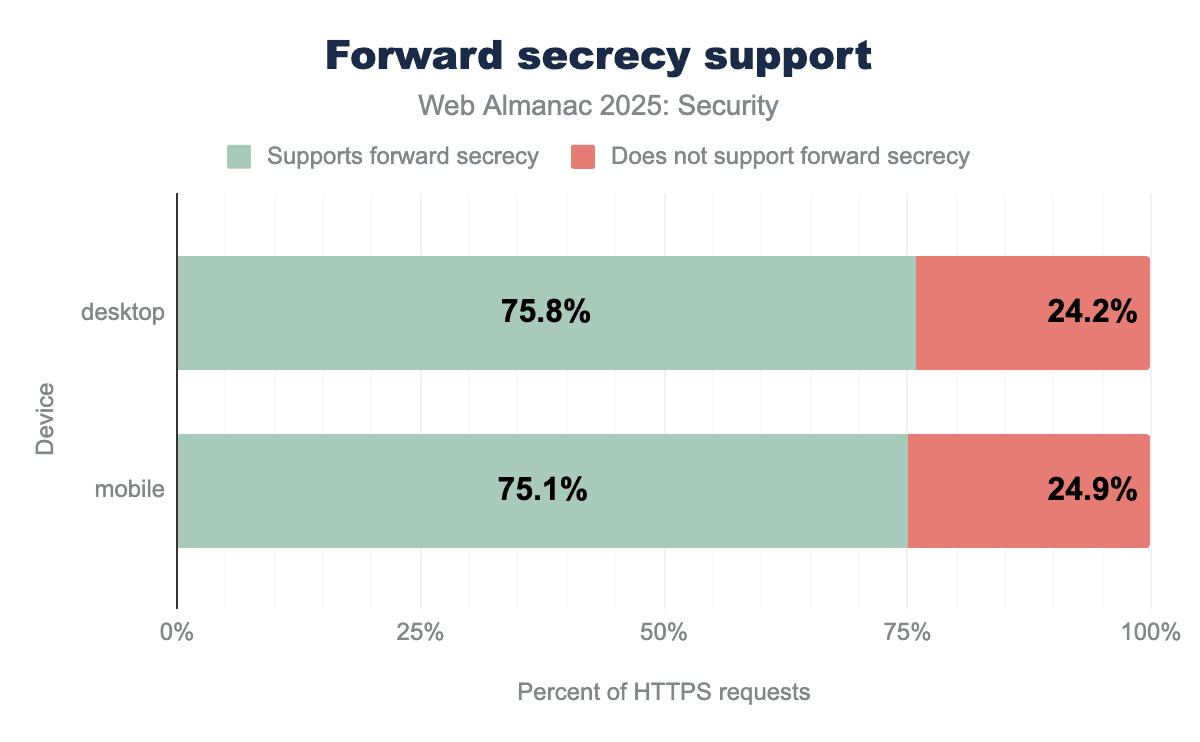

AES_256_GCM serves as the second most common suite, accounting for approximately 16.1% of traffic, while modern alternatives like CHACHA20_POLY1305 and legacy modes like AES_256_CBC represent only a tiny fraction (less than 1%) of web connections.TLS1.3 only allows the use of algorithms that support forward secrecy. Because of the high adoption of TLS1.3, we expect a large share of requests to fulfill the forward secrecy requirement.

Contrary to our expectations, we see a relatively low number of requests that are sent over connections that are forward secret. There is a 20% decrease in forward secret requests since the 2024 Web Almanac. Currently, it seems our metric only includes the forward secret ciphers in TLS1.2 and TLS1.3, but does not include TLS in QUIC which can explain the decline we observer.

Certificate Authorities

In order to use TLS, sites must request a certificate from a Certificate Authority (CA). Because the browser trusts a number of CAs, a site’s certificate can be identified by the browser as a valid certificate. The certificate can then be used for secure communication between the browser and the site’s server going forward.

| Issuer | Desktop | Mobile |

|---|---|---|

| R11 | 20.80% | 21.86% |

| R10 | 20.75% | 21.73% |

| WE1 | 16.35% | 17.24% |

| E6 | 4.50% | 4.65% |

| E5 | 4.31% | 4.42% |

| Sectigo RSA Domain Validation Secure Server CA | 3.60% | 3.52% |

| Go Daddy Secure Certificate Authority - G2 | 1.77% | 1.60% |

| WR1 | 1.16% | 1.40% |

| Amazon RSA 2048 M02 | 1.37% | 1.33% |

| Amazon RSA 2048 M03 | 1.30% | 1.25% |

Compared to last year, we can see that the then popular R3 intermediate certificate from Let’s Encrypt has disappeared as an issuer. This was expected because it has since expired (in September 2025) so even last year the replacement with other intermediates had already started. The R10 and R11 intermediate certificates are the new certificates that are taking over from R3. There are now two intermediate RSA certificates (R10 and R11) and two intermediate ECDSA certificates (E5 and E6) with the explicit goal of trying to prevent intermediate key pinning. The only certificate in the top 5 issuers that is not from Let’s Encrypt is WE1, which is part of Google Trust Services (GTS). Also from GTS in the list is WR1. These certificates seem part of the new generation of intermediate certificates from GTS, expiring among others the GTS CA 1P5 issuer seen last year.

The total share of sites using a certificate from Let’s Encrypt has gone down slightly to 52.6% from 56% in the last edition. One of the contributing factors, as can be seen in the data, is the larger share of certificates issued by the WE1 certificate from GTS. However, the total share by GTS-issued certificates (WE1 and others) has not been calculated.

HTTP Strict Transport Security

HTTP Strict Transport Security is a response header through which servers can instruct browsers to only visit pages on this domain over HTTPS, instead of trying HTTP first and following the redirect to HTTPS.

We see a continuing increase in the number of pages using an HSTS header, with a rise of 6 percentage points compared to last edition, up to 36% of all pages visited on mobile.

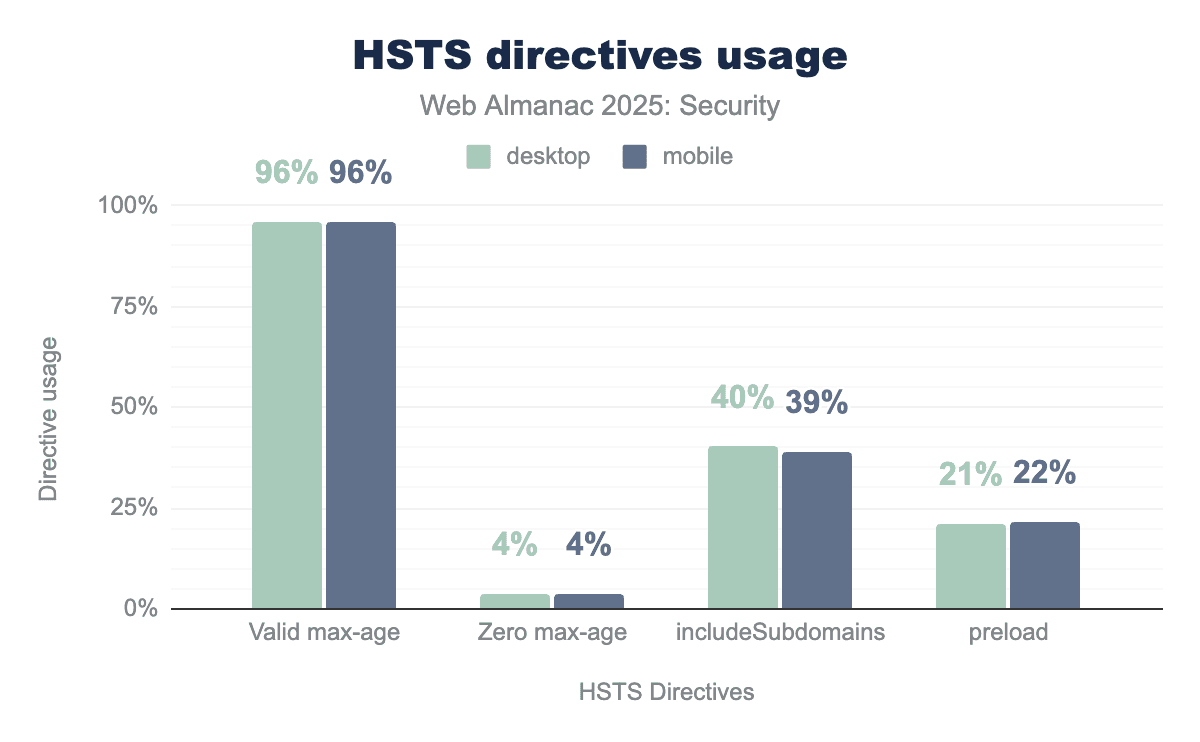

Servers can include a number of directives in the header to communicate additional preferences to the browser. For example, the max-age directive tells the browser how long it is required to continue using only HTTPS. The other directives, includeSubDomains and preload, are optional.

max-age directive to specify how long the browser should enforce secure connections, while only 4% use a zero max-age to disable the policy. Adoption remains significantly lower for advanced security features, with roughly 40% of sites protecting their subdomains and only about 22% utilizing the preload directive to ensure a secure connection from the very first visit.The share of responses with a valid max-age has increased slightly to 96%. The includeSubdomains and preload directives saw an increase of about 4% each, possibly indicating that certain sites started setting both directives together. The unofficial preload directive requires the includeSubdirectories to be set and the max-age to have a value of at least 1 year. When using the preload directive, a site can make sure that a browser will always visit the domain and its subdomains over HTTPS, even when connecting for the first time (which is not necessarily the case when using HSTS without preload).

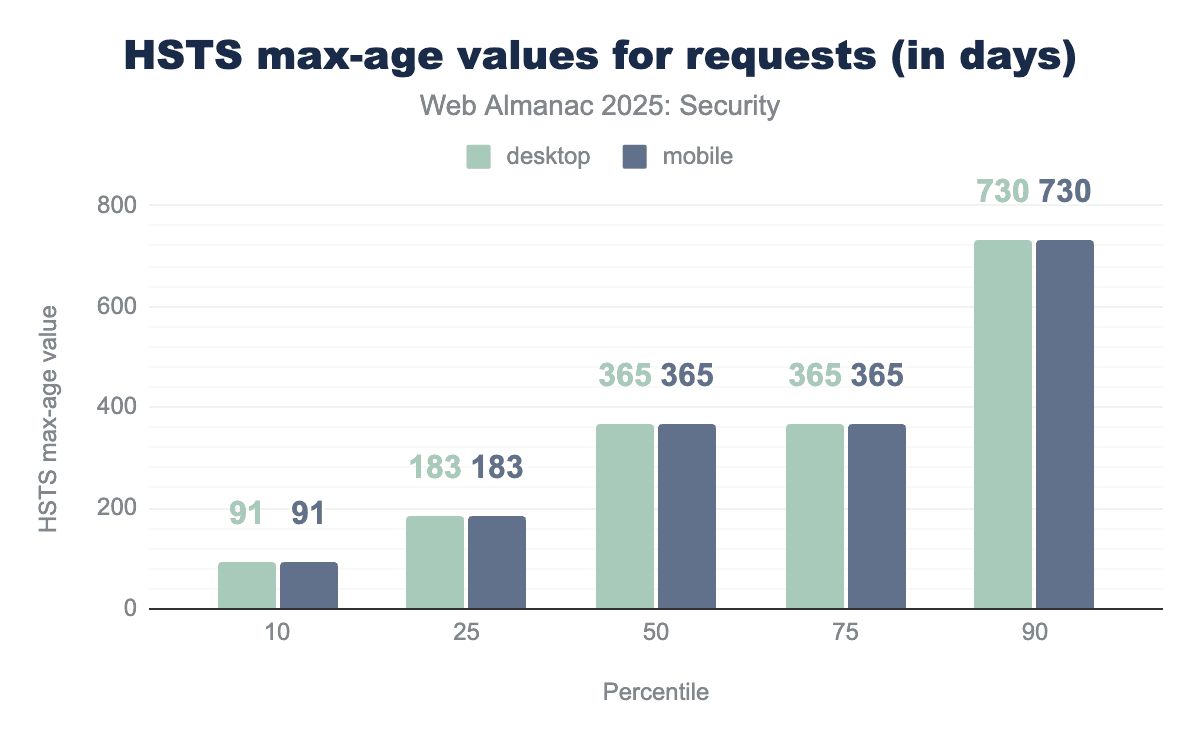

max-age values by percentile.

The distribution of valid max-age values remains largely the same with the exception of the lower percentiles. At the 10th percentile, we see a large increase from 30 days to 91 days, indicating that less sites are setting very low max-age values. The median remains at one year or 365 days.

Cookies

Cookies are a vital part of the web. They allow websites to save information for use over multiple stateless requests. In order to secure sites’ cookies, there are many features built into browsers that are further reported on in the Cookies chapter. We specifically refer to the Cookie attributes, Cookie prefixes and Persistence (expiration) sections in this chapter.

Content inclusion

Content inclusion is a core component of the web. Being able to include other pages, CSS or JavaScript from a Content Distribution Network (CDN) or images from shared sources is one of the building blocks on which the web was built. It does however introduce certain risks such as sites including content from third parties which places significant trust in those third-party resources. Of course, there is no guarantee that said resource is not malicious or compromised by a malicious actor which can lead to a number of serious attacks such as supply chain attacks. To reduce this risk, it is important to use security policies to control content inclusion.

Content Security Policy

The Content Security Policy (CSP) allows websites to have fine-grained control over the content that will be loaded on its page. By setting the Content-Security-Policy response header or defining it in a <meta> html tag, websites can communicate the policy in use to the browser, which will enforce it. The policy has many available directives that allow a website to define from which sources content can be loaded or not.

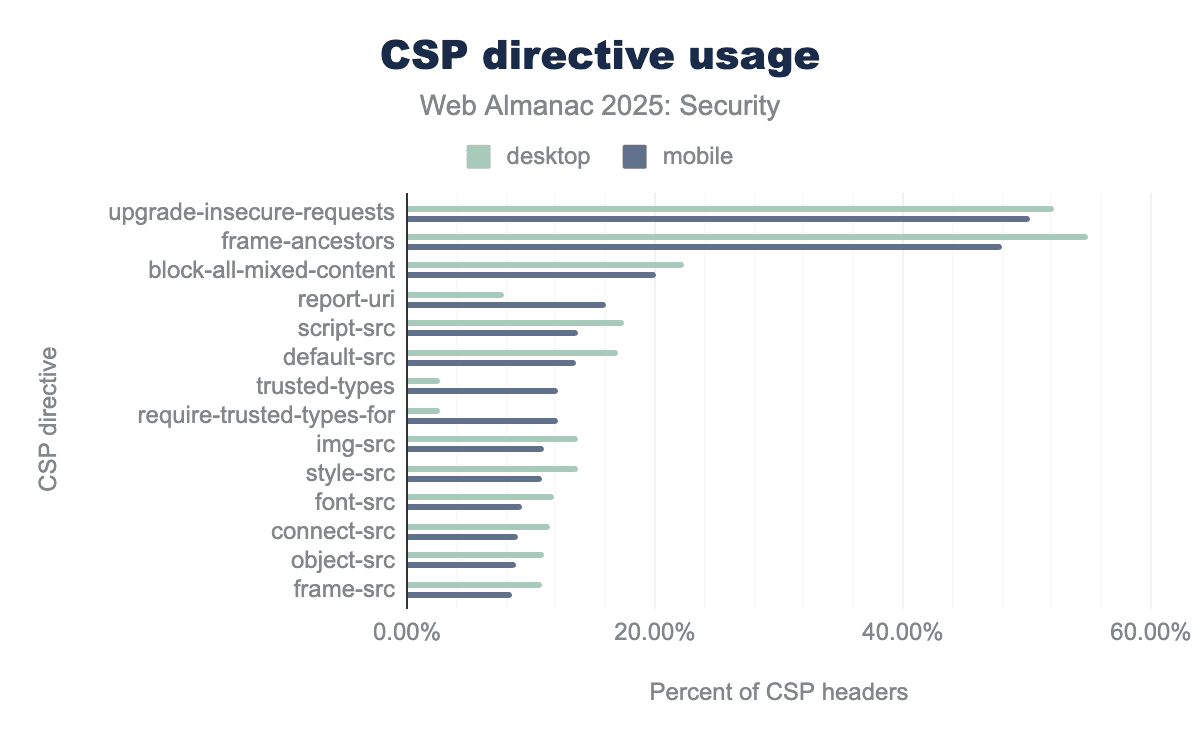

CSP can be used to block specific resources from being loaded, which can help reduce the impact of potential cross-site scripting (XSS) attacks. In addition CSP can also serve other purposes, such as enforcing the use of encrypted communication channels by means of the update-insecure-requests directive or controlling on which pages the current page can load as a subresource using the frame-ancestors directive. This allows websites to defend against clickjacking attacks.

Content-Security-Policy header from 2024.

The adoption of CSP continued increasing from 18.5% last year to 21.9% this year, an increase of close to 20%. As predicted in the last edition of the Web Almanac, the adoption has now risen above 20%, indicating the adoption is still steadily rising.

Directives

upgrade-insecure-requests and frame-ancestors, both appearing in approximately 50-55% of CSP headers to manage secure connections and prevent clickjacking. While desktop sites generally lead in traditional directive usage, mobile sites show significantly higher adoption for modern security features like trusted-types and report-uri.Once again, most websites use CSP for the upgrade-insecure-requests and frame-ancestors directives. The relative share of mobile sites using these directives has decreased slightly, which can be attributed to the higher number of CSP headers scanned. The absolute number has risen by 400,000 and 800,000 CSP headers on desktop and mobile respectively.

The block-all-mixed-content directive which has been replaced by upgrade-insecure-requests has continued to slightly decrease like it has been over the last few years. This is good news because the directive is deprecated.

| Policy | Desktop | Mobile |

|---|---|---|

upgrade-insecure-requests |

21.45% | 22.79% |

block-all-mixed-content; frame-ancestors 'none'; upgrade-insecure-requests; |

19.92% | 18.06% |

require-trusted-types-for 'script';report-uri /checkin/_/AndroidCheckinHttp/cspreport |

2.67% | 12.10% |

frame-ancestors 'self' |

7.55% | 6.38% |

upgrade-insecure-requests; |

4.92% | 4.30% |

frame-ancestors 'self'; |

2.53% | 2.29% |

The same header values we saw last year in the top three appear in this year’s top four again. The third most common CSP header this year is a new one, however. This change occurs because this year, we sorted the most common headers by mobile usage instead of by desktop usage like last year. We can see a trusted types policy with a specific report-uri endpoint relating to Android appear at the third place.

Trusted types can be used to restrict the parameters passed into injection sinks (like element.innerHTML) such that they only allow properly typed values to be passed instead of plain strings. By restricting the values passed to injection sinks, many possible DOM XSS vulnerabilities can be prevented. The trusted types header we observe appears on more than 12% of the mobile pages. We don’t have a direct explanation for the high usage of this specific CSP policy value.

In fifth and sixth place we once again see the upgrade-insecure-requests and frame-ancestors 'self' directives, but this time with a trailing semicolon. A semicolon is used to separate directives but if there is only one directive defined it can be discarded, both header values are therefore valid CSP policies with the same effect.

Keywords for script-src

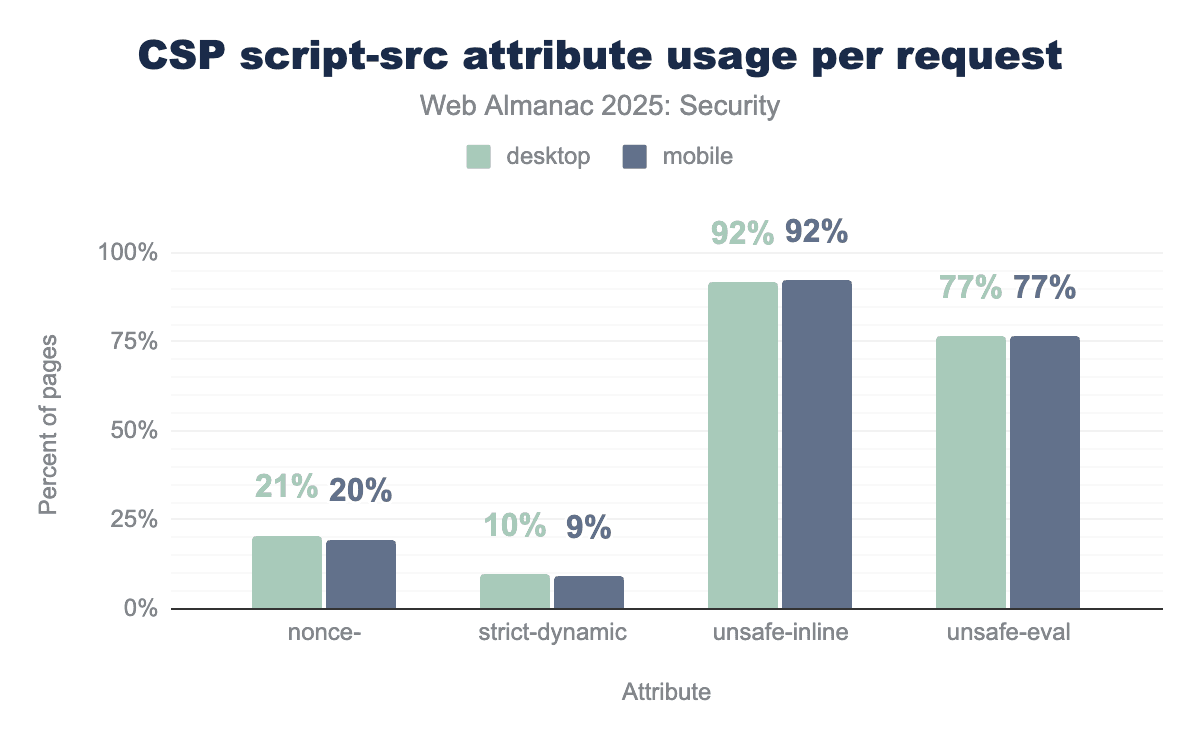

One of the most important directives included in the CSP is script-src. Through the use of this directive, websites can control which scripts can run on their pages. This can hinder attackers because it can disallow them from running arbitrary scripts. script-src has multiple potential keywords.

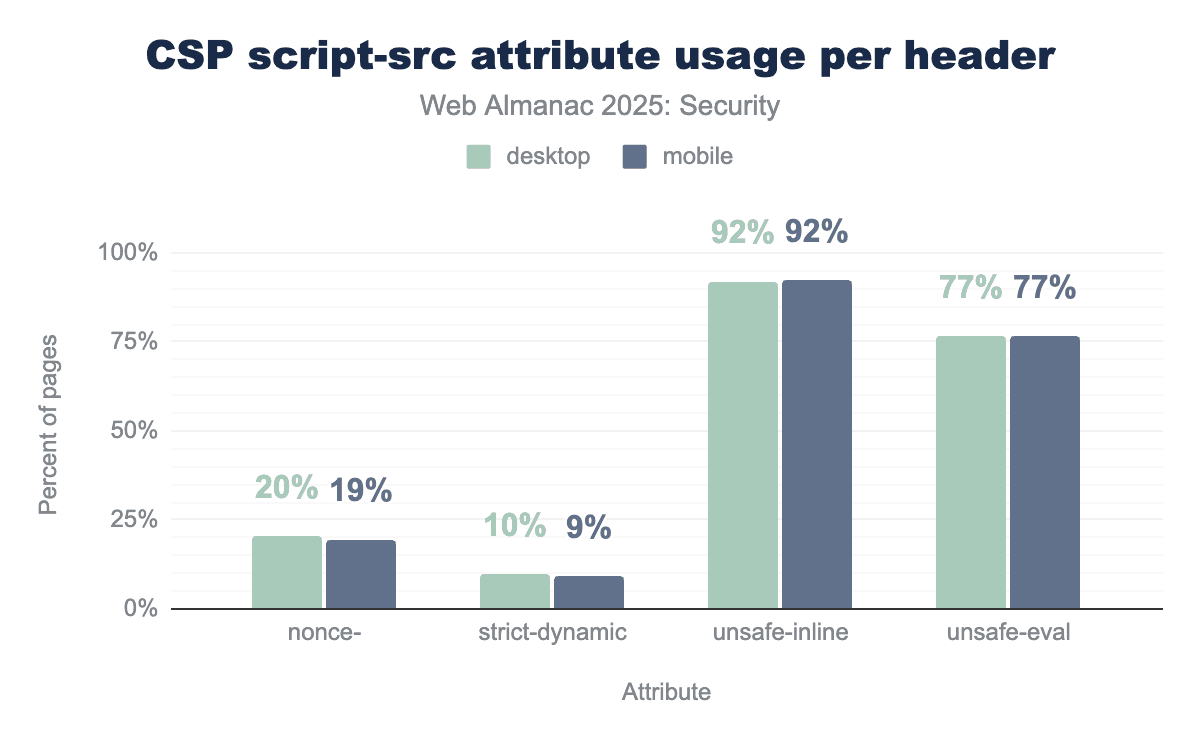

script-src attributes. An overwhelming 92% of websites use the unsafe-inline attribute on both desktop and mobile, unsafe-eval is present in 77% of policies, with nonces used on approximately 20% of sites and strict-dynamic only on approximately 10%.script-src keywords per request.

We find that the unsafe-inline and unsafe-eval keywords are used very often. These keywords significantly reduce the security impact of CSP’s script-src as they allow any inline script to be executed or allow the use of the eval-function in JavaScript respectively.

Compared to last year we barely see any changes to the usage of script-src keywords. An important note to make is that the presence of unsafe-inline does not necessarily mean that inline scripts can be executed. In some cases and following the CSP specification unsafe-inline will be ignored. This is for instance the case when a nonce and strict-dynamic keywords are added to the CSP policy.

script-src attributes per header. An overwhelming 92% of headers use the unsafe-inline attribute on both desktop and mobile, unsafe-eval is present in 77% of policies, with nonces used on approximately 20% of sites and strict-dynamic only on approximately 10%script-src keywords per header.

We also check the use of keywords per header instead of per page. In CSP, multiple CSP headers can be present in one response and may define different directives. If a directive is defined multiple times, the policies will be combined to create the the most restrictive policy to be used by the browser.

We see a very similar distribution compared to the values per request, indicating that either most pages only use one CSP header or only use script-src in one of the CSP headers that they set, meaning there are no conflicting script-src directives on most pages.

Allowed hosts

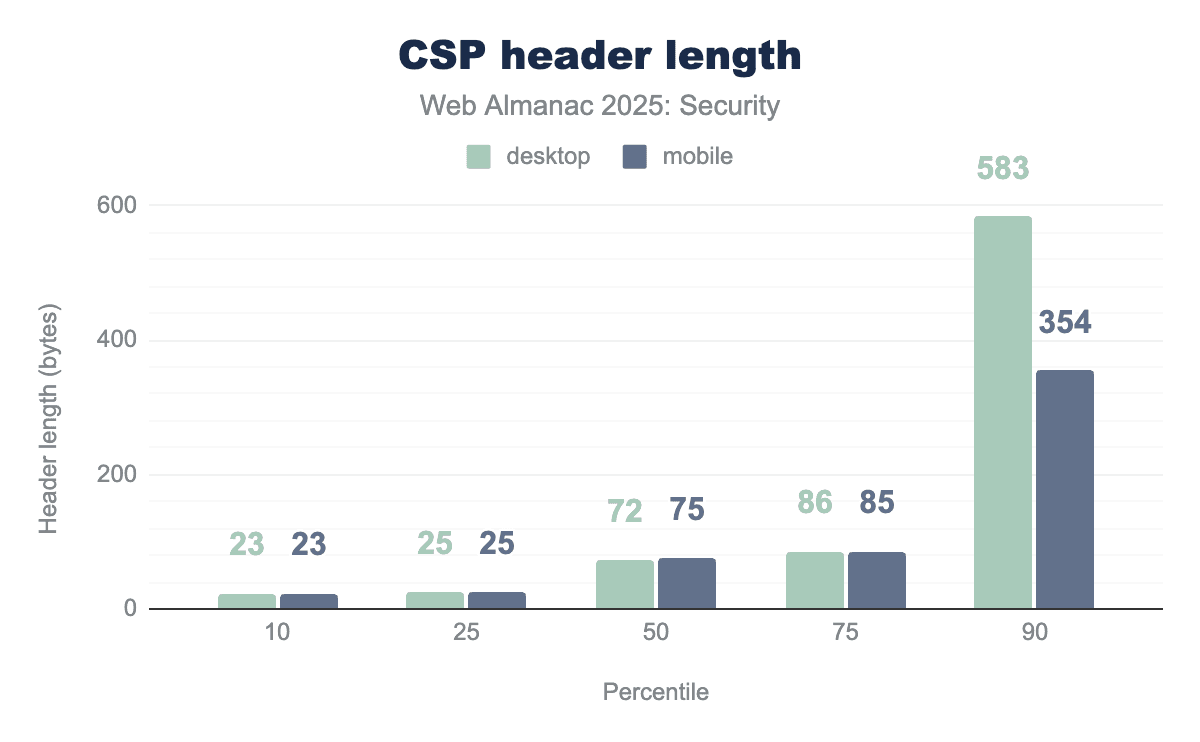

CSP is a complex security policy to thoroughly understand and correctly use. When looking at the length of the CSP headers in use, we can see a wide variety in policy sizes.

Out of all observed headers, 75% are 86 bytes or less in length. This is slightly more than last year where this was 75 bytes or less. We can see that there are more longer policies in use and in the 90th percentile. The desktop policies have gotten longer while the mobile policies have gotten slightly shorter, increasing the difference between the policy lengths.

| Host | Desktop | Mobile |

|---|---|---|

https://www.googletagmanager.com |

0.74% | 0.62% |

https://fonts.gstatic.com |

0.61% | 0.49% |

https://fonts.googleapis.com |

0.60% | 0.48% |

https://www.google.com |

0.54% | 0.46% |

https://www.google-analytics.com |

0.47% | 0.38% |

https://www.youtube.com |

0.41% | 0.34% |

https://*.google-analytics.com |

0.35% | 0.31% |

https://*.google.com |

0.31% | 0.30% |

https://connect.facebook.net |

0.33% | 0.29% |

https://www.gstatic.com |

0.35% | 0.27% |

The most commonly loaded HTTPS origins included in CSP headers are those used for ads, fonts and other CDN resources.

| Host | Desktop | Mobile |

|---|---|---|

wss://*.hotjar.com |

0.18% | 0.15% |

wss://*.intercom.io |

0.07% | 0.07% |

wss://booth.karakuri.ai |

0.08% | 0.06% |

wss://www.livejournal.com |

0.04% | 0.05% |

wss://*.quora.com |

0.03% | 0.05% |

wss://tsock.us1.twilio.com/v3/wsconnect |

0.02% | 0.04% |

wss://api.smooch.io |

0.05% | 0.03% |

wss://*.zopim.com |

0.05% | 0.03% |

wss://*.pusher.com |

0.04% | 0.03% |

wss://cable.gumroad.com |

0.04% | 0.03% |

For the secure websocket (wss://) origins, we see Hotjar take the first position, doubling in occurrences. Other origins remain low in occurrence.

Hotjar is used for website analytics, indicating a continuing interest in analytical information of websites while Intercom is used for customer services. We also see AI-first companies entering these statistics with karakuri, a Japanese AI company that is closing the top three.

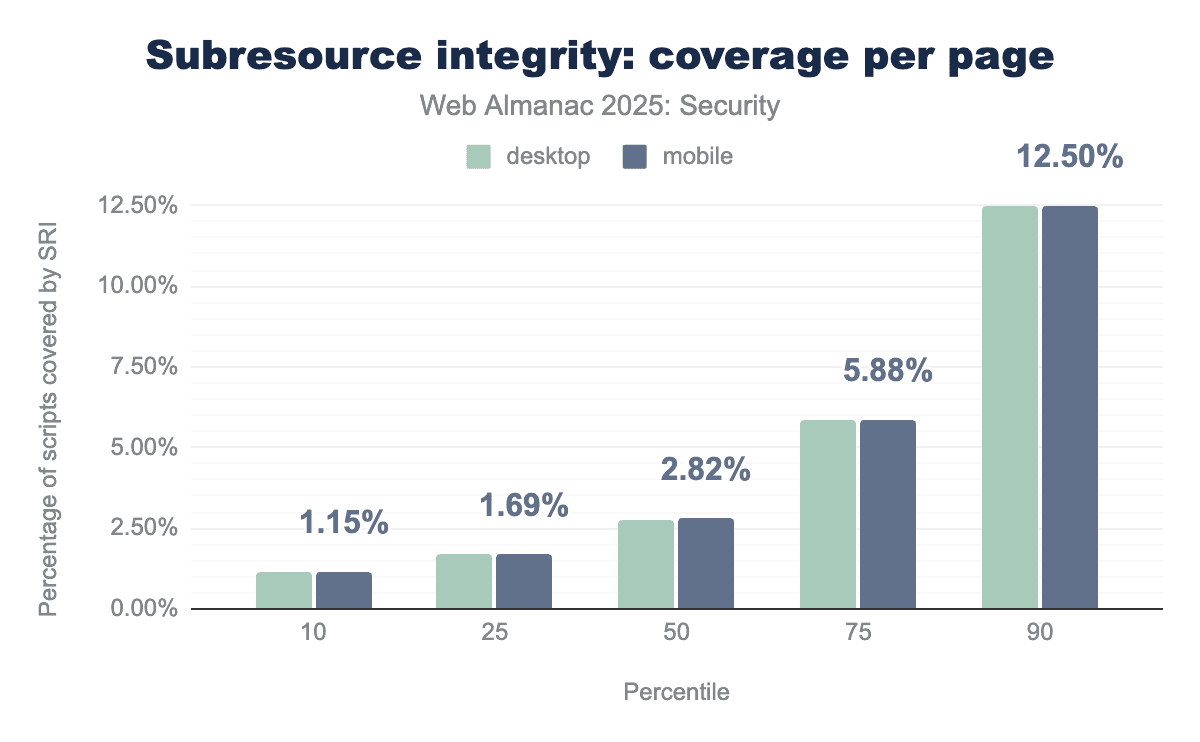

Subresource Integrity

In order to protect themselves from loading tampered resources, developers can make use of Subresource Integrity (SRI). While CSP allows for developers to restrict the sources from which resources are loaded, SRI makes sure those resources contain the content that is expected by the developer. The opposite can be the case when for instance a CDN is compromised and an attacker succeeds in changing a valid script into a malicious one.

By using the integrity attribute in <script> and <link> tags, developers can communicate to the browser the expected hash of the resource. When loading the specified resource, the browser will then check whether the hash of the resource contents corresponds to the provided hash and if not, refuse to load/execute the resource, thereby protecting the website from potentially compromised content.

SRI is used on 25.9% and 23.6% of desktop and mobile pages respectively. This is a rise by around 2.5% for both numbers since last year, showing that a growing number of developers are using SRI to protect their pages.

Compared with last year, we see a drop in median subresource coverage per page by 0.41%. It is likely that this drop is caused by the larger number of pages being crawled by the web almanac crawler this year.

| Host | Desktop | Mobile |

|---|---|---|

www.gstatic.com |

34.70% | 34.55% |

static.cloudflareinsights.com |

8.89% | 8.37% |

cdnjs.cloudflare.com |

7.43% | 7.20% |

cdn.userway.org |

6.10% | 6.60% |

code.jquery.com |

4.96% | 4.77% |

cdn.shoplineapp.com |

4.62% | 5.22% |

cdn.jsdelivr.net |

4.50% | 4.06% |

d3e54v103j8qbb.cloudfront.net |

2.03% | 2.30% |

The list of most common hosts from which SRI-protected scripts are loaded has remained largely stable over time, with some entries moving relative positions. The cloudflareinsights record for instance has increased in relative occurrence, but only by 2.40%.

Like last year, most of these entries are CDNs, showing that most resources loaded and protected by SRI are loaded from CDNs. This makes sense because these scripts are often not under direct control of the developers. Often, CDNs will host a large number of scripts that can then be included by many developers. This is advantageous for developers because the load on their own servers will go down, but also for the client because it can cache scripts from the CDN instead of loading the same script once for every website that includes it.

The risk of including a script that is hosted on a server not under your own control is higher than when you as developer have full control. If the developer of this external script decides to include malicious content or the server is compromised and the script is swapped with a malicious one, without SRI the developer’s users will be loading and executing this malicious content. A good way to protect users against these unexpected changes and to know with certainty which script is allowed to run is to use SRI.

Permissions Policy

The Permissions Policy (formerly Feature Policy) is a policy that enables websites to allow or disallow the use of specific features in the browser, such as the camera, microphone, sensors (like the accelerometer) or geolocation data. Through the Permissions-Policy response header, developers can allow or disallow specific feature use by the main page and its embedded content. A specific policy for one embedded resource can be set through the allow attribute of the <iframe> element.

Permissions-Policy header from 2024 (mobile).

Compared to last year, the use of the Permissions-Policy saw a relative increase of almost 60%. Although this is a large relative increase, the absolute percentage of websites using Permissions-Policy remains rather small at 3.7% on mobile. The rise in adoption is a good sign for the policy.

| Header | Desktop | Mobile |

|---|---|---|

interest-cohort=() |

11.02% | 11.56% |

accelerometer=(), autoplay=(), camera=(), encrypted-media=(), fullscreen=(), geolocation=(), gyroscope=(), magnetometer=(), microphone=(), midi=(), payment=(), picture-in-picture=(), publickey-credentials-get=(), screen-wake-lock=(), sync-xhr=(), usb=() |

5.01% | 10.00% |

geolocation=(),midi=(),sync-xhr=(),microphone=(),camera=(),magnetometer=(),gyroscope=(),fullscreen=(self),payment=() |

4.63% | 4.44% |

accelerometer=(), autoplay=(), camera=(), cross-origin-isolated=(), display-capture=(self), encrypted-media=(), fullscreen=*, geolocation=(self), gyroscope=(), keyboard-map=(), magnetometer=(), microphone=(), midi=(), payment=*, picture-in-picture=*, publickey-credentials-get=(), screen-wake-lock=(), sync-xhr=*, usb=(), xr-spatial-tracking=(), gamepad=(), serial=() |

3.65% | 3.45% |

geolocation=(self) |

2.06% | 2.64% |

accelerometer=(), camera=(), geolocation=(), gyroscope=(), magnetometer=(), microphone=(), payment=(), usb=() |

2.77% | 2.38% |

accelerometer=(self), autoplay=(self), camera=(self), encrypted-media=(self), fullscreen=(self), geolocation=(self), gyroscope=(self), magnetometer=(self), microphone=(self), midi=(self), payment=(self), usb=(self) |

2.39% | 2.25% |

browsing-topics=() |

1.82% | 2.14% |

geolocation=(), microphone=(), camera=() |

2.11% | 2.09% |

geolocation=self |

1.87% | 1.81% |

Permission-Policy headers

When looking at the top 10 used Permissions-Policy values, we find that less developers now use the header to opt out of Google’s Federated Learning of Cohorts (FLoC), with only 11.5% of Permissions-Policy headers containing the interest-cohort=() value. We also see that a value to opt out of many features at once became a popular value with 10% of Permissions-Policy headers containing this value on mobile. We suspect this is due to it being replaced by the Topics API with a different permission policy. This is also likely to reduce further in the future since Google is retiring these Privacy Sandbox APIs.

All other observed values in the top 10 are aimed at restricting the permissions of the web page and embedded content. The Permissions Policy is open by default, which means that in order to restrict the use of a feature, it has to be explicitly mentioned in the header. Like last year, 0.27% of Permissions-Policy headers on desktop set the * wildcard value, thereby explicitly granting all permissions to the page and embedded content that does not define a stricter policy in the allow attribute. On mobile, we do not find the wildcard value at all.

As mentioned before, the Permissions Policy can also be defined in the allow attribute on an html <iframe>. For example an iframe allowing its embedded content to have access to the camera and microphone would look like:

<iframe src="https://example.com/" allow="camera 'self'; microphone 'self'">Out of the total 33.3 million iframes on mobile, we observed that 29.2% include an allow attribute. The relative decrease in use of the allow attribute can be attributed to the more than 10 million more iframe elements that were found in this year’s crawl that included more pages than last year’s.

| Directive | Desktop | Mobile |

|---|---|---|

encrypted-media |

60.90% | 70.66% |

autoplay |

34.99% | 41.83% |

picture-in-picture |

26.10% | 36.63% |

gyroscope |

23.76% | 34.20% |

accelerometer |

23.76% | 34.20% |

clipboard-write |

20.39% | 26.24% |

join-ad-interest-group |

24.23% | 17.35% |

web-share |

12.07% | 15.67% |

attribution-reporting |

3.93% | 2.35% |

run-ad-auction |

3.84% | 2.26% |

allow attribute directives

Interestingly, the three top allow attribute values of last year (join-ad-interest-group, attribution-reporting and run-ad-auction) have extremely low adoption compared to last year. It is possible that the large player that was hypothesized to have added these values to their iframe elements has since reverted that change. The other top 10 values of last year have seen a major increase in inclusion into the allow attribute value overall, with absolute changes up to +50%.

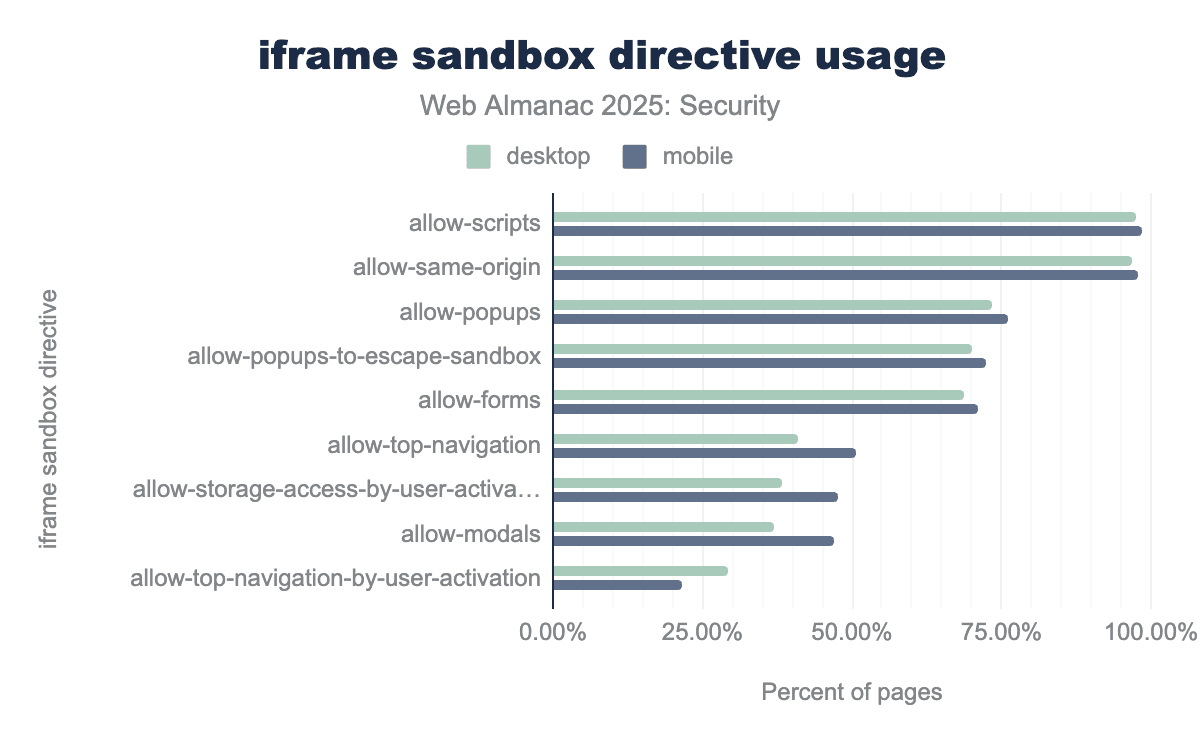

Iframe sandbox

By employing the sandbox attribute on <iframe> elements, developers can protect their users against several attacks in which a resource embedded in an <iframe> is either compromised or malicious. In the sandbox attribute’s value, developers can specify which restrictions should be put into place for the content loaded and displayed in the <iframe>. For example, the following <iframe> would allow the embedded webpage to run scripts:

<iframe src="https://example.com/" sandbox="allow-scripts"></iframe>We see the use of the sandbox attribute rise compared to the 2024 edition from 20.0% to 22.7%, showing that more and more developers want to protect their users against potential misuse by embedded content.

allow-scripts and allow-same-origin are nearly universal, appearing in approximately 97-98% of sandboxed pages to ensure that embedded content maintains core functionality like JavaScript execution and access to its own storage. Moderately common features include allow-popups and allow-popups-to-escape-sandbox, which are utilized by about 70-75% of sites, while specialized navigation controls like allow-top-navigation-by-user-activation are the least adopted at under 30%.Like last year, we see that out of all iframes with the sandbox attribute, 98.5% (on mobile) use it to allow the embedded webpage to execute scripts by including the allow-scripts directive. Following in second place, used in 97.8% on mobile iframes, developers use the allow-same-origin to make the loaded resources part of the embedder’s origin.

Emerging security headers

In general we see a rise in most of the existing security features such as TLS, HSTS, CSP policies, SRI and the iframe sandbox attribute. Besides these existing features, as time keeps moving, new attacks are crafted and more defenses are being implemented. This section goes over the relatively new Document Policy that is starting to show up more often in the wild.

Document Policy

Document Policy is a draft community group report last updated in 2022. It was originally created as a response to proposed additions to Permissions Policy that did not fit the Permissions Policy model or added too much complexity.

Document Policy has several advantages over related mechanisms such as Permissions Policy, CSP and sandboxing. It is more fine-grained than Permissions Policy and has a different inheritance model: child resources can overwrite certain parent-chosen policies if they are compatible. It is more general than CSP as it has directives related to the permissions of a resource once it has been loaded instead of only determining from which origins resources can be loaded. It is easier to extend than sandboxing because features that are not mentioned in sandboxing are blocked by default, which makes it very difficult to add new ones.

| Header | Desktop | Mobile |

|---|---|---|

include-js-call-stacks-in-crash-reports |

68.48% | 71.99% |

js-profiling |

12.66% | 15.24% |

js-profiling; include-js-call-stacks-in-crash-reports |

17.41% | 11.94% |

force-load-at-top |

1.25% | 0.65% |

no-font-display-late-swap |

0.06% | 0.05% |

We can see that of the Document Policy headers in use, more than two thirds of them are used to include call stacks in crash reports. Combined with the js-profiling directive these two features make up the vast majority of current use-cases. Currently in total we find policy values containing 19 different directives. In general there may be more directives defined but as of now we are not aware of the total number them.

We currently only find just over 24,000 and 29,500 pages for desktop and mobile respectively which is 0.10% of the total number of pages visited for both. We expect to see a rise in adoption of Document Policy headers going forward, although future adoption may not happen quickly.

Attack preventions

While there are many defenses for websites implemented by many browsers, it can be challenging to keep an overview of all the possibilities and best practices. In addition, when protections are opt-in and therefore not enabled by default, it becomes even more of a challenge. Developers have to remain up to speed with modern attacks and the defenses that exist to protect users against these attacks. This section assesses which attack prevention measures are in use across the web.

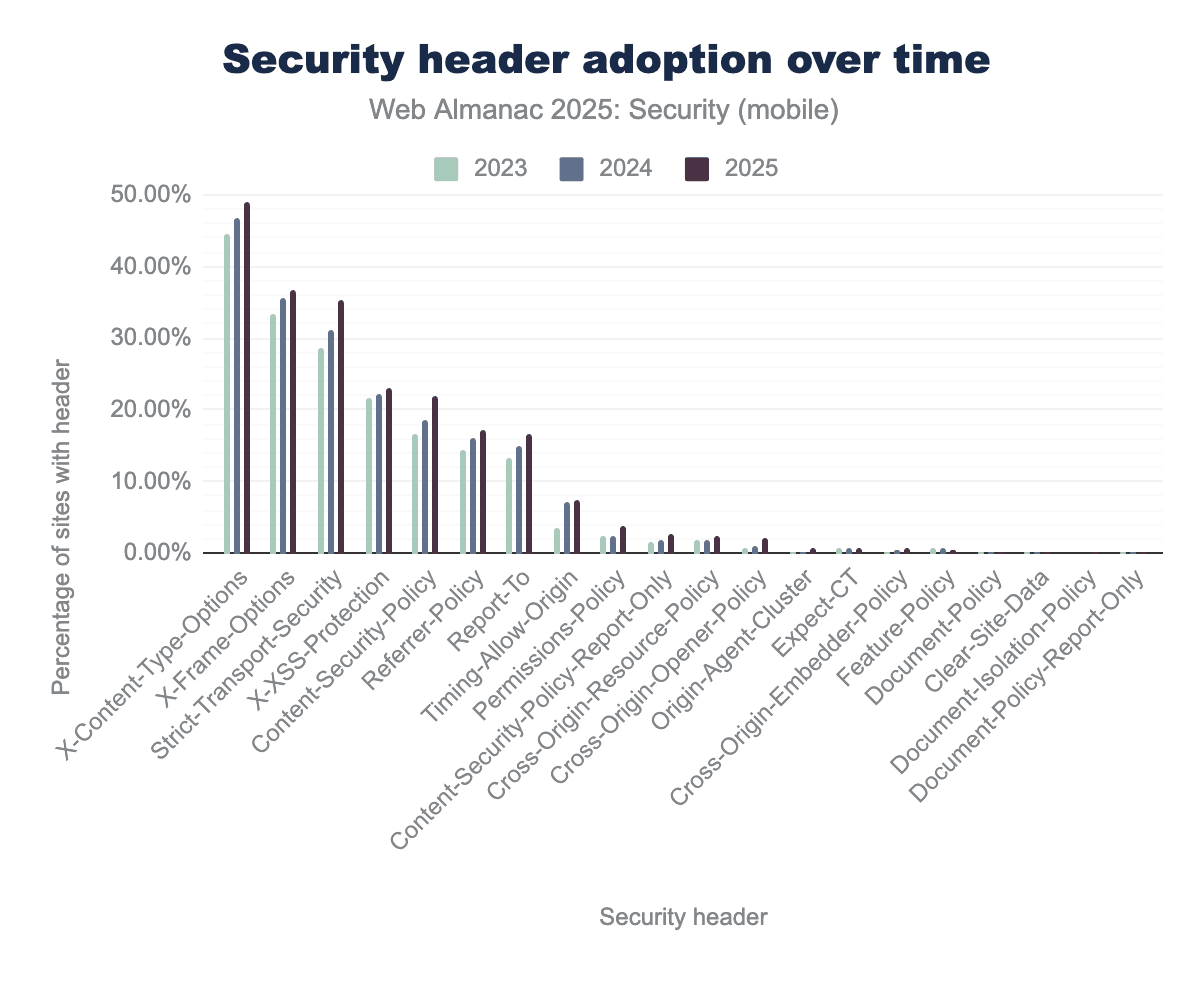

Security header adoption

A multitude of protection mechanisms can be configured through HTTP response headers. Based on the values of these headers the browser will enforce these protections. Not all security mechanisms are relevant for every website, but the absence of all security headers can point to missing urgency towards security.

X-Content-Type-Options leading the group at nearly 50 percent adoption by 2025. Other prominent headers like X-Frame-Options and Strict-Transport-Security follow closely, showing steady increases to approximately 35 percent of sites. Meanwhile, more modern or niche headers such as Cross-Origin-Opener-Policy and Permissions-Policy remain in the early stages of adoption, staying well below the 10 percent threshold.Like last year there are only a few headers for which adoption decreased. The Feature-Policy header is deprecated in favor of the Permissions-Policy, therefore it’s no surprise that the adoption is declining. The other two: Clear-Site-Data and Document-Policy-Report-Only have such low adoption (0.01% and 0.00001% respectively) that relative changes in adoption may seem large while absolute differences are actually small. This means that the overall adoption of security headers keeps increasing over time, which is a positive sign for web security overall.

The strongest risers since the 2024 edition are Strict-Transport-Security (+4.02%), Content-Security-Policy (+3.39%) and X-Content-Type-Options (+2.30%).

Origin-Agent-Cluster

The Origin-Agent-Cluster, when correctly set, communicates to the browser a request to share the resources used for the document (like the operating system process) with documents of the same origin. The browser may or may not honor the request and the client can verify using JavaScript whether the request was in fact honored.

Usage remains low with only 0.47% of mobile sites, and 0.38% desktop sites using this, but let’s dig into what they are using it for:

| Header | Desktop | Mobile |

|---|---|---|

?1 |

74.11% | 90.32% |

?0 |

25.79% | 9.60% |

1 |

0.08% | 0.07% |

0 |

0.01% | 0.01% |

Origin-Agent-Cluster header values

A boolean is defined in the HTML living standard as a string starting with a question mark. This means that values like 1 and 0 are invalid for this header. Luckily the use of these values is limited. The ?1 value is the only valid value for the Origin-Agent-Cluster and it’s used to communicate that the developer wants to opt into the feature, all other values are ignored. On mobile, more than 90% of headers have the valid ?1 value. Unfortunately, 0.07% of header values are 1, a value that will be ignored while the developer likely wants to request the use of dedicated resources.

Use of document.domain

By using document.domain, a developer is able to read the domain portion of the current document, as well as set a new domain (only superdomains of the current domain are allowed), after which the browser will use the new domain as origin for the same-origin policy checks. However, the use of this property is now deprecated and browsers may stop supporting the property soon.

| Blink Feature | Desktop | Mobile |

|---|---|---|

DocumentSetDomain |

0.49% | 0.36% |

DocumentDomainSetWithNonDefaultPort |

0.16% | 0.14% |

DocumentDomainEnabledCrossOriginAccess |

0.0008% | 0.0004% |

DocumentDomainBlockedCrossOriginAccess |

0.0002% | 0.0001% |

DocumentOpenAliasedOriginDocumentDomain |

0.00008% | 0.00001% |

document.domain based on specific blink features

We see that less than 0.5% of websites on desktop and mobile are using the document.domain setter to change the origin of a page and even less sites do so with a non-default port. This is a positive trend but still represents a few tens of thousands of websites that should update their code.

Preventing clickjacking with CSP and X-Frame-Options

As previously mentioned, a Content Security Policy (CSP) can be effective against Clickjacking attacks through the use of the frame-ancestors directive. Some of the top CSP header values include a frame-ancestors directive with a 'none' or 'self' value, thereby blocking embedding of the page overall or restricting the embeddings to pages of the same origin.

Another way of defending against clickjacking attacks is through the X-Frame-Options (XFO) header. By setting the XFO header, developers can communicate that a document cannot be embedded in other documents (’DENY’) or can only be embedded in documents of the same origin (SAMEORIGIN).

| Header | Desktop | Mobile |

|---|---|---|

SAMEORIGIN |

72.48% | 72.13% |

DENY |

24.40% | 24.64% |

ALLOWALL |

0.68% | 0.72% |

SAMEORIGIN, SAMEORIGIN |

0.27% | 0.28% |

allow-from https://s.salla.sa |

0.16% | 0.28% |

X-Frame-Options header values

We find that there are barely any changes between the data this year and in 2024. The X-Frame-Options header is primarily used to allow same-origin websites to embed the page (72.1%). Secondly, it is used to deny any page from embedding its own content (24.6%).

Examples of other values we observe are shown in the third to fifth row of the table. The ALLOW-FROM value used to be valid but is now deprecated and ignored by browsers. Instead of using ALLOW-FROM in XFO, developers should switch to using the frame-ancestors directive in CSP. These out-of-spec values do not show up often, but may have been set by developers expecting protections to be active due to them setting the header.

Preventing attacks using Cross-Origin policies

Because of the emergence of microarchitectural side-channel attacks like Spectre and Meltdown and Cross-Site Leaks (XS-Leaks), our security perspective relating to use and embeddings of cross-origin resources has changed. In response to these threats, new mechanisms were created to control the rendering of resources on other websites and thereby protect against these new threats.

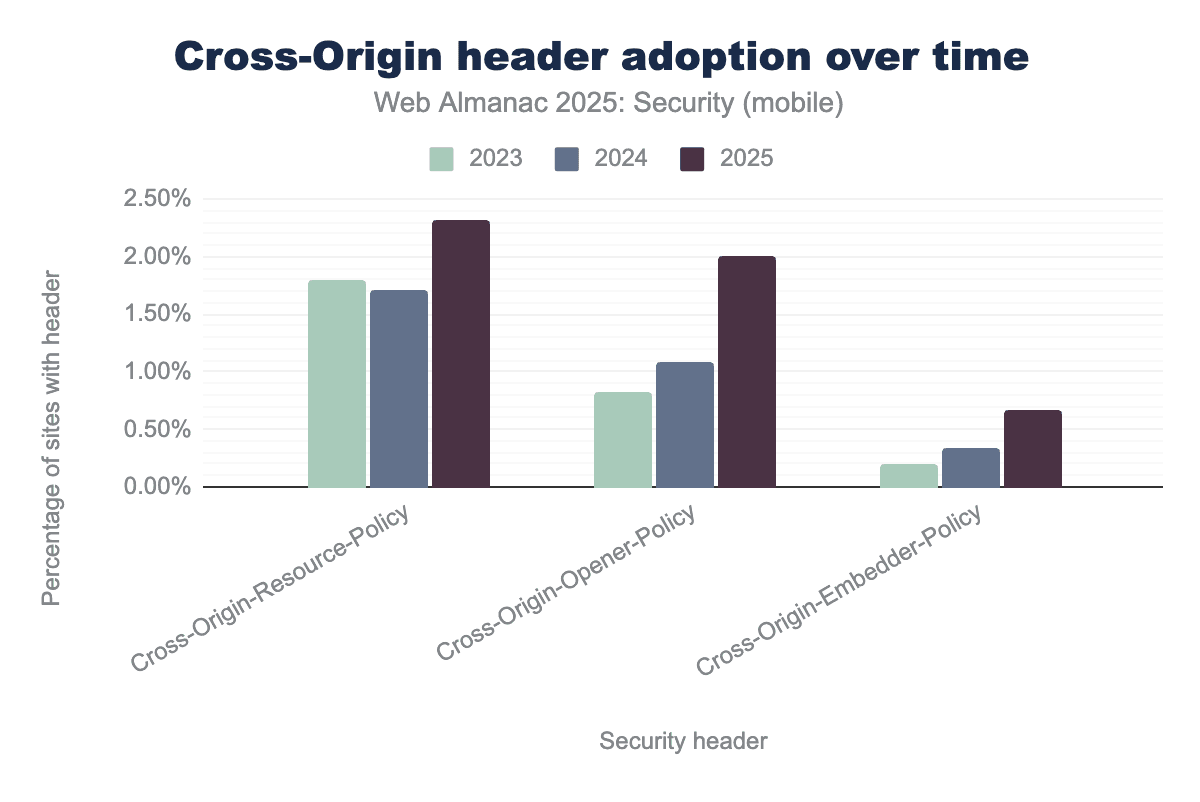

Multiple new security headers, known as the cross-origin policies, were created as a response to these challenges: Cross-Origin-Resource-Policy (CORP), Cross-Origin-Embedder-Policy (COEP) and Cross-Origin-Opener-Policy (COOP). These headers provide mechanisms that protect against side-channel attacks by allowing developers to control how their resources are embedded across different origins. We observe that the adoption of all of these headers keeps growing year after year, with both CORP and COOP reaching over 2% adoption this year.

Cross-Origin-Resource-Policy remains the most widely adopted of the three, growing from approximately 1.75% in 2023 to over 2.25% by 2025. Cross-Origin-Opener-Policy experienced the most significant relative growth, more than doubling its adoption from under 1.00% to roughly 2.00% over the three-year period. While Cross-Origin-Embedder-Policy remains the least common, it demonstrates a steady upward trend, reaching nearly 0.75% adoption by 2025.Cross Origin Embedder Policy

The Cross-Origin-Embedder-Policy (COEP) allows a developer to configure which cross-origin resources can be embedded on the current document. By default (when the header is absent) all cross-origin resources can be embedded on the page, which is the same behaviour as when the header is set with the unsafe-none value.

| COEP value | Desktop | Mobile |

|---|---|---|

unsafe-none |

83.26% | 86.52% |

require-corp |

6.68% | 4.92% |

credentialless |

2.59% | 1.89% |

Compared to last year, most developers still set the COEP header to explicitly allow all content to be embedded onto the current document using the unsafe-none value. While the percentage of use of this value is still over 86% on mobile, it has dropped by almost 2% since last year, which can indicate that developers are starting to change their use of the header.

The other values require-corp and credentialless saw a minor increase of 0.2% and 0.3% respectively in adoption since last year. When using require-corp, the browser will enforce that only same-origin content or cross-origin content that is allowed to be embedded by CORP can be embedded onto the page.

For credentialless, the browser will allow cross-origin requests in no-cors mode regardless of CORS policy of the content, but cookies will not be attached to the request.

Cross Origin Resource Policy

Related to COEP, the Cross-Origin-Resource-Policy (CORP) does not enforce which content can be embedded in the current document, but rather from which documents the current content can be accessed.

The only three possible values are cross-origin, same-origin and same-site. The cross-origin value allows any document to access the resource, while the same-origin and same-site values restrict which documents can access the resource to the documents in the same origin or site respectively. Developers should be aware of the difference between the origin (scheme, host, port) and site (registerable domain). If the header is present, requests with a mode of no-cors will be blocked by the browser.

| CORP value | Desktop | Mobile |

|---|---|---|

cross-origin |

81.36% | 80.52% |

same-origin |

14.40% | 15.63% |

same-site |

3.80% | 3.48% |

In most cases, the header is used to allow access to any cross-origin resource. We see a big change in this number this year, dropping more than 10% since last year and landing on 80.5% on mobile. On the other hand, the use of the same-origin value went up around 10%, showing that developers are moving to protect their resources against cross-origin access. The share of use for same-site remained approximately the same, showing a slight decrease of less than half a percent.

Cross Origin Opener Policy

The final cross-origin policy header, Cross-Origin-Opener-Policy (COOP) allows a developer to control how other pages can reference their page when opening it through browser APIs such as window.open.

The default value of unsafe-none allows the COOP protection to be disabled, which is also what happens when the header is absent. If a developer uses window.open to open a page which uses unsafe-none, they can use the returned value to access certain properties of the opened page, which can lead to Cross-Site Leaks.

When same-origin is present on both the opener and opened resource, the reference returned by windows.open can be used by the opener. The same-origin-allow-popups allows a document to open another document with unsafe-none while still keeping access to a working reference.

Finally, the noopener-allow-popups makes sure the reference is never accessible except for when the opened document also has the same COOP value set.

| COOP value | Desktop | Mobile |

|---|---|---|

same-origin |

58.22% | 61.64% |

unsafe-none |

28.47% | 26.82% |

same-origin-allow-popups |

11.36% | 9.95% |

noopener-allow-popups |

0.03% | 0.03% |

The use of the strictest same-origin value for COOP has continued to rise from 47.5% to 61.6% on mobile. The noopener-allow-popups is a very new value and was not present yet last year. This year we see a small share of adopters using this value. The use of unsafe-none had declined by just over 10%. These changes represent a positive evolution in the use of COOP.

Cross-origin isolation

In order to access certain sensitive APIs like SharedArrayBuffer or Performance.now a site has to be cross-origin isolated. In order to be cross-origin isolated, the developer has to set a COEP of same-origin and CORP of either require-corp or credentialless. The browser will then allow access to these APIs again. This strengthens the protection against XS Leaks. These days, developers can opt into cross-origin isolation using the document isolation policy as well.

Preventing attacks using Clear-Site-Data

Using the Clear-Site-Data HTTP response header, developers are able to instruct the client to clear browsing data. The value of the header specifies which type or types of data should be cleared. This can be useful when a user logs out of the website, so the developer can be sure that any authentication cookies are most assuredly cleared.

It is difficult to estimate the adoption of Clear-Site-Data correctly as its use is usually most valuable when logging out users. The crawler we use does not log into websites and therefore can also not log out to check how many sites use the header after logout. For now, we see 2,024 mobile hosts using the Clear-Site-Data header, which is only 0.01% of the total number of hosts crawled.

| Clear site data value | Desktop | Mobile |

|---|---|---|

cache |

30.82% | 29.25% |

* |

17.74% | 20.61% |

cookies |

7.02% | 8.16% |

"cache" |

8.94% | 7.19% |

"storages" |

5.66% | 6.08% |

cache, cookies, storage |

2.12% | 3.23% |

"cache", "cookies", "storage", "executionContexts" |

2.32% | 2.51% |

"cookies" |

2.78% | 2.46% |

"storage" |

2.27% | 2.03% |

"cache", "storage", "executionContexts" |

1.36% | 1.54% |

Clear-Site-Data headers

Our data shows that most developers attempt to use the Clear-Site-Data header for clearing the cache. The most prevalent value is cache, followed by the wildcard character * and cookies. All values from the top three are invalid according to the specification. The value of this header must be a ’quoted string’, which means "cache", "*" and "cookies" are the equivalent valid values. This is concerning as the top three values combined already represent 58.01% of current header values on mobile.

We see these numbers jump quite a lot year after year, which can likely be explained by the low adoption of the header, where a very small number of hosts can change the relative fraction by a large amount.

Preventing attacks using <meta>

Besides being set via response headers, some of the security mechanisms of the web can be configured directly within the html document through the use of the <meta> tag. Two examples of this are the Content-Security-Policy and the Referrer-Policy. The use of a meta tag for these mechanisms has remained largely stable from last year, at around 0.60% and around 2.50% for the CSP and Referrer-Policy respectively. A very small decrease in CSP and very small increase in Referrer-Policy could be observed, just like last year.

| Meta tag | Desktop | Mobile |

includes Referrer-policy |

2.75% | 2.52% |

includes CSP |

0.64% | 0.59% |

includes not-allowed policy |

0.12% | 0.11% |

Other security mechanisms cannot be configured through the use of the <meta> tag, however every year we see developers still attempt this. This year we even see a rise in policies that are not allowed to be configured using a meta tag from 0.07% to 0.11% on mobile. These values are ignored by the browser, thus potentially leaving users vulnerable if the correct header is not configured. Keeping up with our running example, this year we found 5,564 meta tags that included the X-Frame-Options policy. This is almost 600 pages more than last year, which is a worrying trend.

Web Cryptography API

The Web Cryptography API is a JavaScript API that provides an interface for performing basic cryptographic operations. Examples of such operations are the creation of random numbers, hashing, signing content, verifying signatures and of course encryption and decryption.

| Feature | Desktop | Mobile |

|---|---|---|

CryptoGetRandomValues |

34.45% | 40.95% |

SubtleCryptoDigest |

2.65% | 2.98% |

CryptoAlgorithmSha256 |

2.36% | 2.48% |

SubtleCryptoImportKey |

1.29% | 1.68% |

CryptoAlgorithmEcdh |

0.97% | 1.39% |

CryptoAlgorithmSha512 |

0.17% | 0.32% |

CryptoAlgorithmSha1 |

0.21% | 0.26% |

CryptoAlgorithmAesCbc |

0.21% | 0.17% |

SubtleCryptoSign |

0.13% | 0.14% |

SubtleCryptoEncrypt |

0.13% | 0.12% |

CryptoAlgorithmHmac |

0.10% | 0.11% |

The CryptoGetRandomValues function remains the most widely used feature of this API, however it is still declining in use, just like it was last year. Its use on mobile dropped by more than 12% this year, landing just under 41%. The other features continue to rise, with the second most popular feature SubtleCryptoDigest growing by 1.2% to just under 3%.

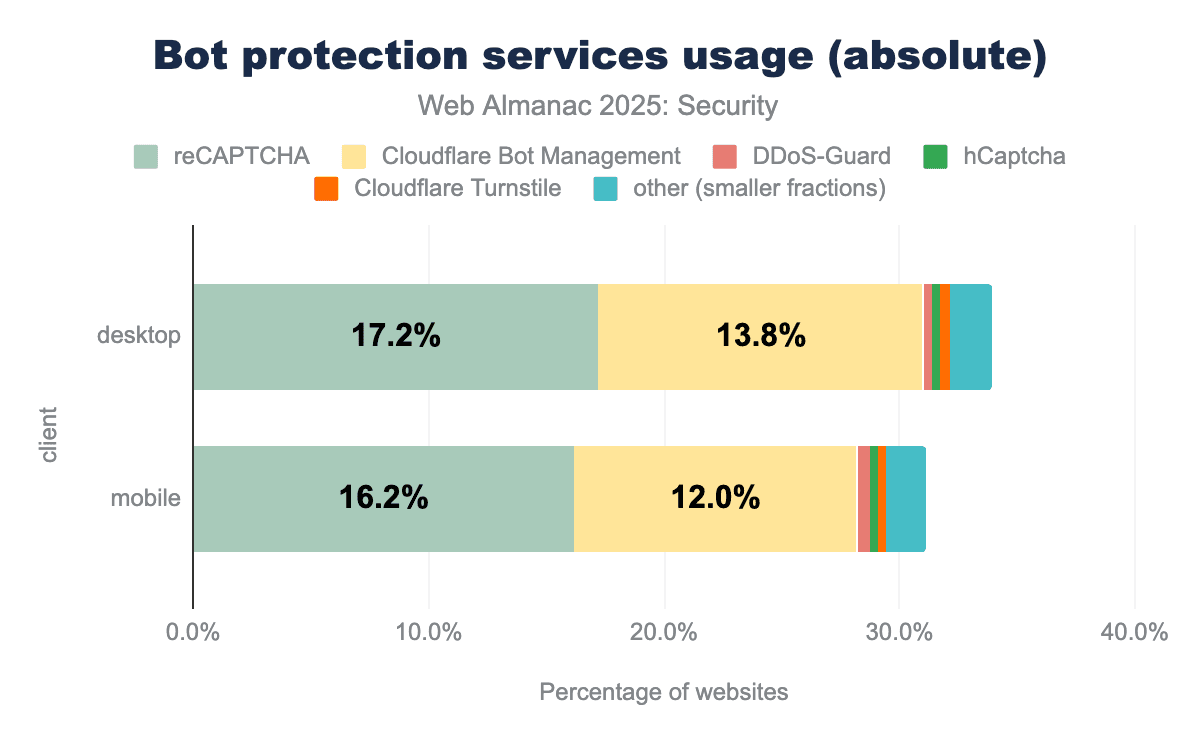

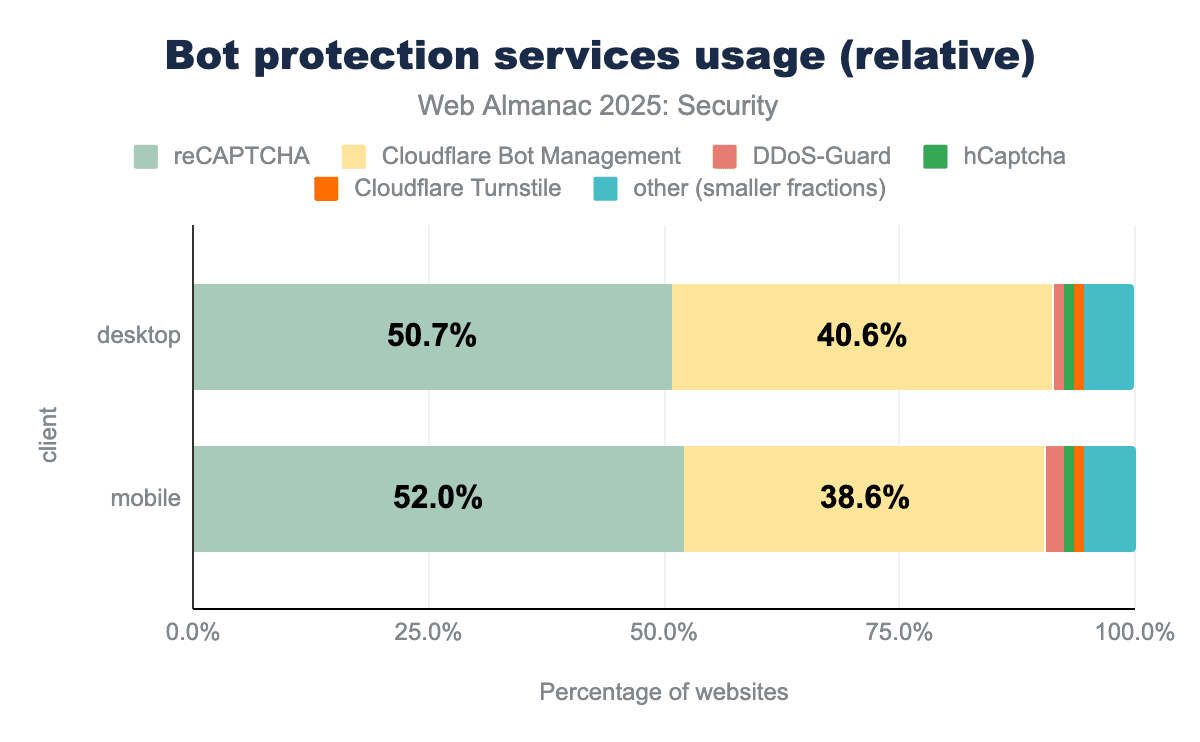

Bot protection services

Bots have been present on the web for a long time, and malicious bots are a large part of that. Because of these issues, many products have been created by different vendors to protect websites against bots. The use of these products continues to rise year after year, including this year, where we see a jump from 26.5% to 31.1% adoption on mobile, a rise of over 4.5%.

We see that reCAPTCHA remains the largest bot protection service, but Cloudflare Bot Management is growing more rapidly, thereby taking up a larger relative share of websites using bot protection services. In case these trends continue over the next year, we may see Cloudflare Bot Management closing the gap on reCAPTCHA.

HTML sanitization

With the SetHTMLUnsafe and ParseHTMLUnsafe APIs, two relatively recent additions to browsers, developers can use a declarative shadow DOM from JavaScript.

When a developer attempts to use innerHTML to place a custom HTML component that includes a definition for a declarative shadow DOM onto the page (for example <template shadowrootmode="open">...</template>), this will not work as expected. By using SetHTMLUnsafe or ParseHTMLUnsafe the developer can ensure that the declarative shadow DOM is properly instantiated by the browser.

As the name implies, the developer is responsible for making sure that only safe values are passed to these ’unsafe’ APIs. In other cases, the developer runs the risk of allowing dangerous content to end up on the page, which can lead to XSS attacks.

| Feature | Desktop | Mobile |

|---|---|---|

ParseHTMLUnsafe |

19869 | 17147 |

SetHTMLUnsafe |

443 | 449 |

Since last year, we see a big rise in the use of these APIs. On mobile, the number of pages using SetHTMLUnsafe rose from 2 to 449 pages and the number using ParseHTMLUnsafe rose from 6 to 17,147 this year. The latter still only accounts for 0.06% of the crawled pages, but it is an interesting change and we can expect the adoption to keep rising in the following year. However, it is not expected that these APIs will gain widespread adoption anytime soon.

Drivers of security mechanism adoption

There may be various reasons that web developers choose to adopt more security practices. Some of the most noteworthy are:

- Geographical: depending on the region, there may be more security-oriented education or knowledge, or in some cases there can be local laws that mandate stricter security hygiene.

- Technological: the technology stack in use can influence the adoption of security mechanisms. Depending on the technology in use, some security features will be enabled out of the box without the developer having to think about enabling them.

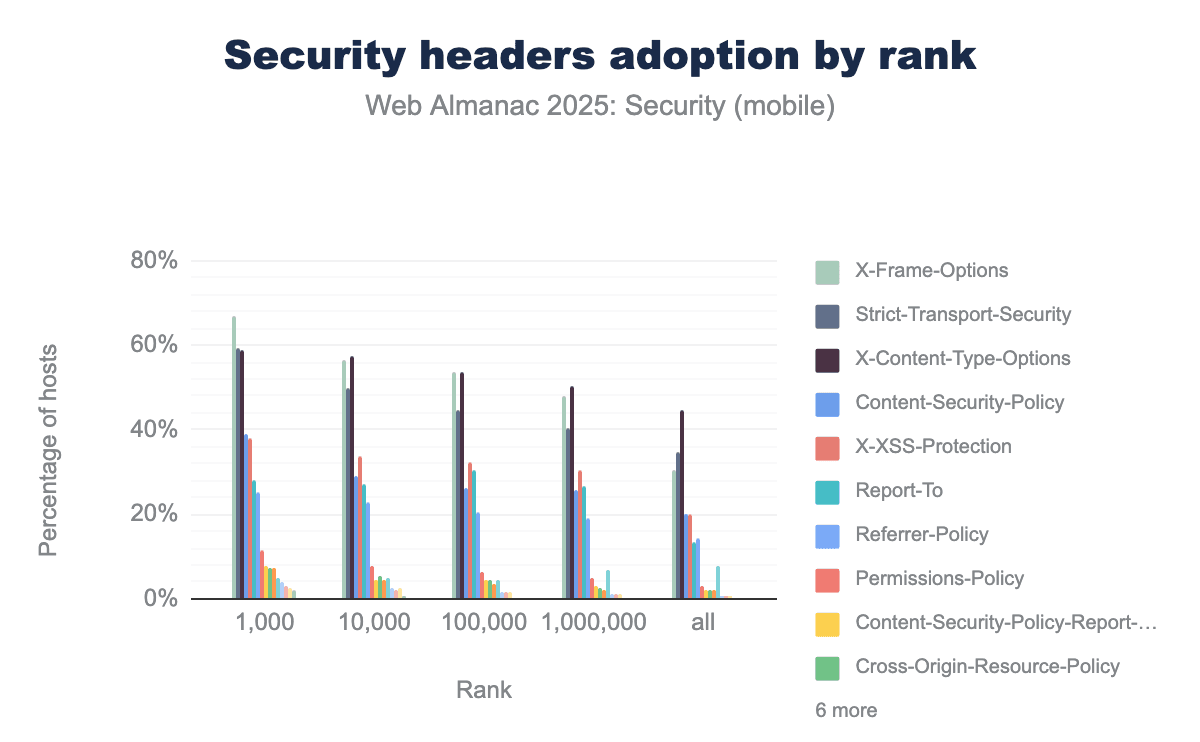

- Popularity: very popular websites may have larger budgets for security, in part because they are more likely to be the target of certain cyberattacks. In addition, these sites are likely to attract more security professionals and in some cases bug bounty hunters to help them implement security features and strengthen their defenses.

Location of websites

The location where a website is hosted or where its developers are based can have a big impact on the adoption of certain security features. Security education for developers plays a big role, as developers cannot implement features of which they don’t know they exist or which they don’t understand. In addition, local laws can sometimes require the adoption of certain security practices.

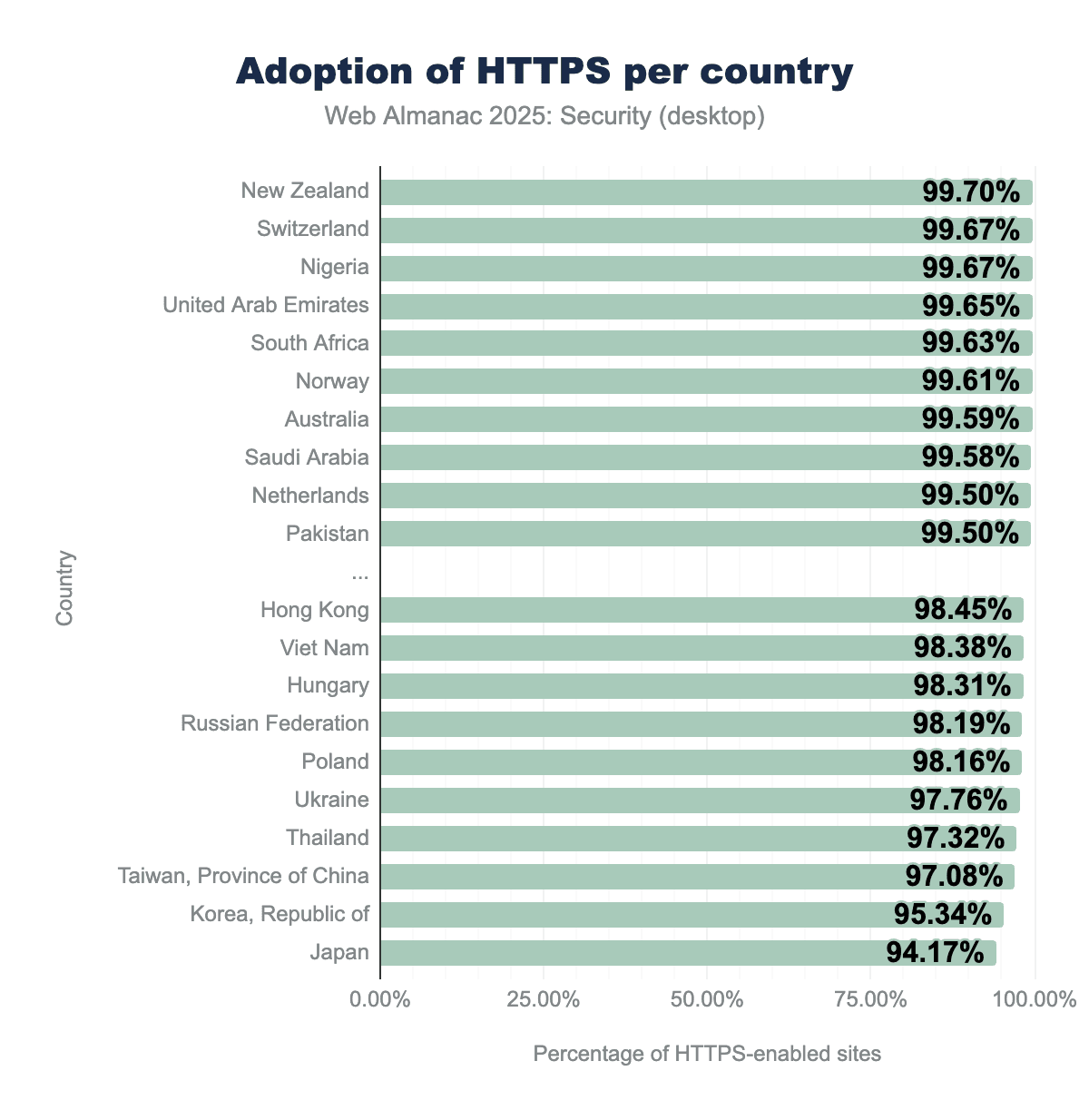

HTTPS adoption has been increasing year after year, a trend that luckily continues this year as well. We see even adoption in the top countries continued to increase by a few tenths of a percentage. The bottom countries saw slightly larger rises in HTTPS adoption, with Japan now being the only country with adoption under 95% and only five countries having less than 98% adoption of HTTPS, an extremely good result. In the following years, we can expect the bottom countries to slowly catch up with the rate of adoption of the top countries, although a full 100% adoption seems unlikely in the near future.

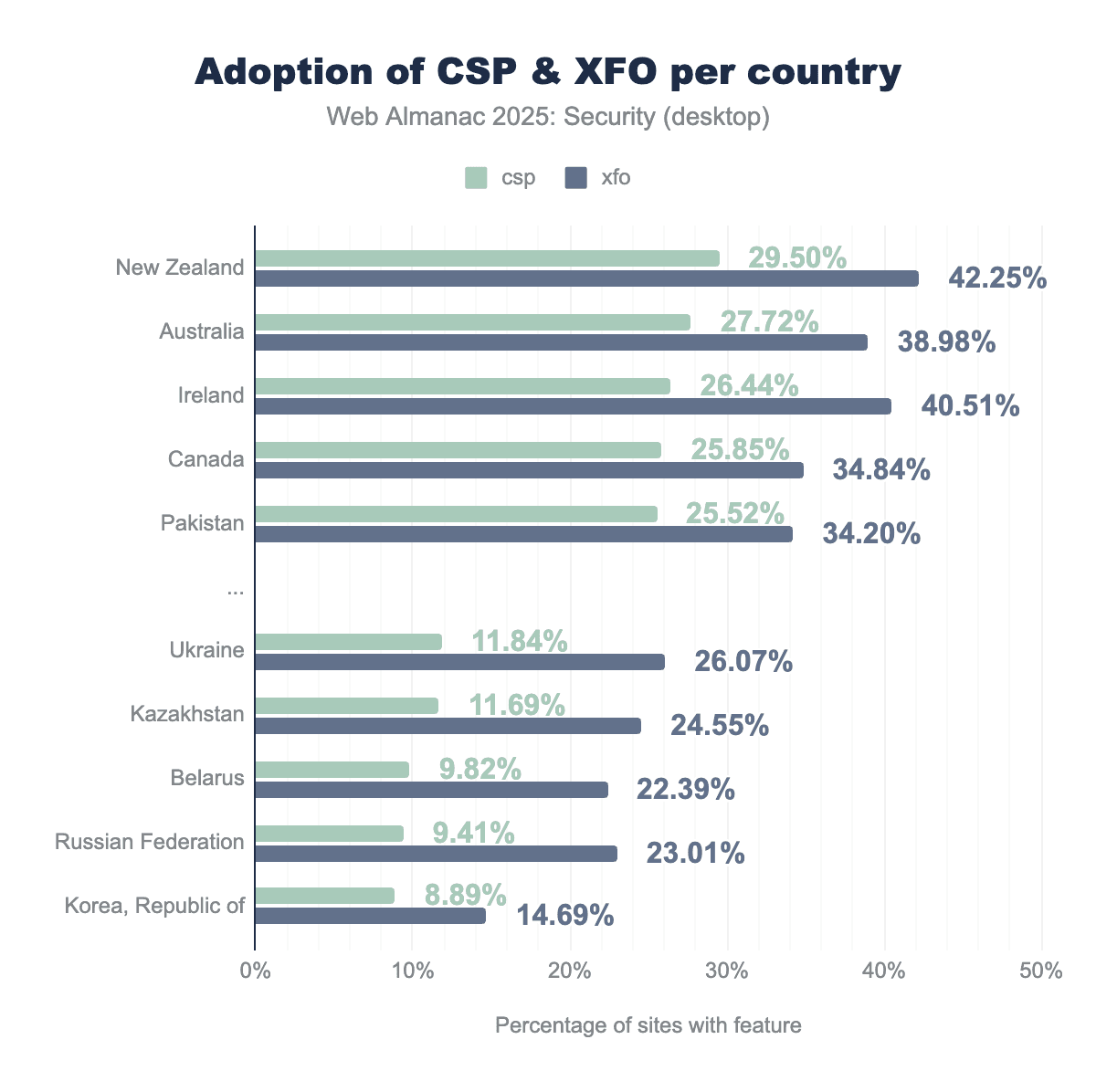

We see a more varied picture when looking at more complex security mechanisms. With a small rise in adoption for most leading countries, some of the bottom countries saw a decline in adoption of these policies. The leading countries still have CSP configured on just over a quarter of the websites. The gap between CSP and XFO remains large, although it has gone up slightly, reaching only up to 14% instead of 15% last year.

Technology stack

A website’s security can vary depending on the technology in use. Because frameworks include security features by default and it is in the best interest of large vendors to keep their users secured, using these underlying technologies may boost a website’s security.

| Technology | Security features |

|---|---|

| LiveJournal | Content-Security-Policy (99.99%), Permissions-Policy (99.99%), Referrer-Policy (99.99%) |

| Weblium | X-Content-Type-Options (97.31%), X-XSS-Protection (97.31%) |

| GoDaddy Website Builder | Strict-Transport-Security (95.97%), Content-Security-Policy (95.97%) |

| Sitevision CMS | X-Frame-Options (81.54%) |

| Microsoft Sharepoint | X-Content-Type-Options (57.44%) |

| Liferay | X-Content-Type-Options (52.65%) |

We see that a number of blogging websites and website builders have some important security mechanisms configured almost throughout all of their systems, with HSTS, CSP and X-Content-Type-Options being some of the most popular ones.

Website popularity

Popular websites with a large user base often have a good reason to protect their users to the best of their abilities so they will not lose users and their trust. Protecting the often sensitive data they store while they likely are the target of more directed attacks requires significant investments in securing their website, but will also lead to a more generally secure website as a trade-off.

X-Frame-Options and Strict-Transport-Security compared to the broader web. For instance, X-Frame-Options adoption exceeds 60 percent for the top 1,000 sites but drops to approximately 30 percent when looking at all sites combined.We find that the most popular security headers like X-Frame-Options, Strict-Transport-Security, X-Content-Type-Options and Content-Security-Policy always have a higher adoption among more popular websites on mobile. The most widely adopted header, X-Frame-Options is used on 67% of the top 1,000 sites yet only on 30% of all sites visited by the browser. We see the gap between the adoption in more popular sites and less popular sites remains practically identical since last year.

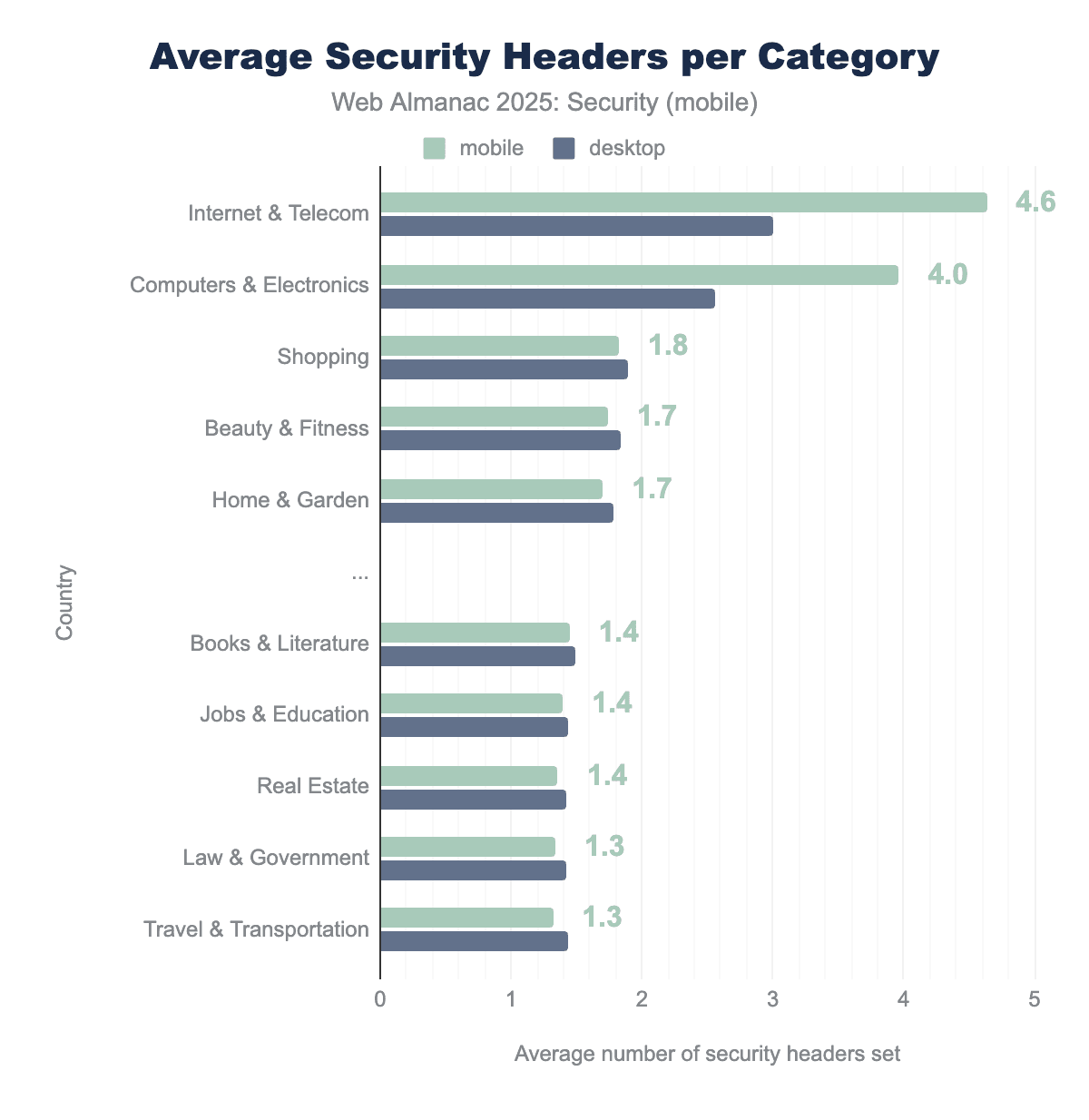

Website category

Depending on the industry, more importance may be attributed to keeping a website more secure. We attempt to estimate the efforts in securing websites per industry based on the average number of security headers set by websites. While the number of security headers does not necessarily indicate whether a website is better secured (after all, security mechanisms can be misconfigured), it provides a good estimate for the effort taken to implement security features.

We see a big difference occurring in the average number of security headers since last year. Sites in the Internet & Telecom and Computers & Electronics categories use significantly more security headers. Especially on mobile clients the difference with these categories is clearly visible. While these two categories seem to be outliers in the good sense, the average number of security headers over other industries has remained largely the same, with a very minor change of about 0.1 header per site on average.

The two leading industries in terms of security headers happen to be industries related to the field of internet and computer security. It is possible that due to the relevance of security in these industries, developers of these sites are more aware of the potential risk and therefore more willing to use certain security mechanisms.

Malpractices on the web

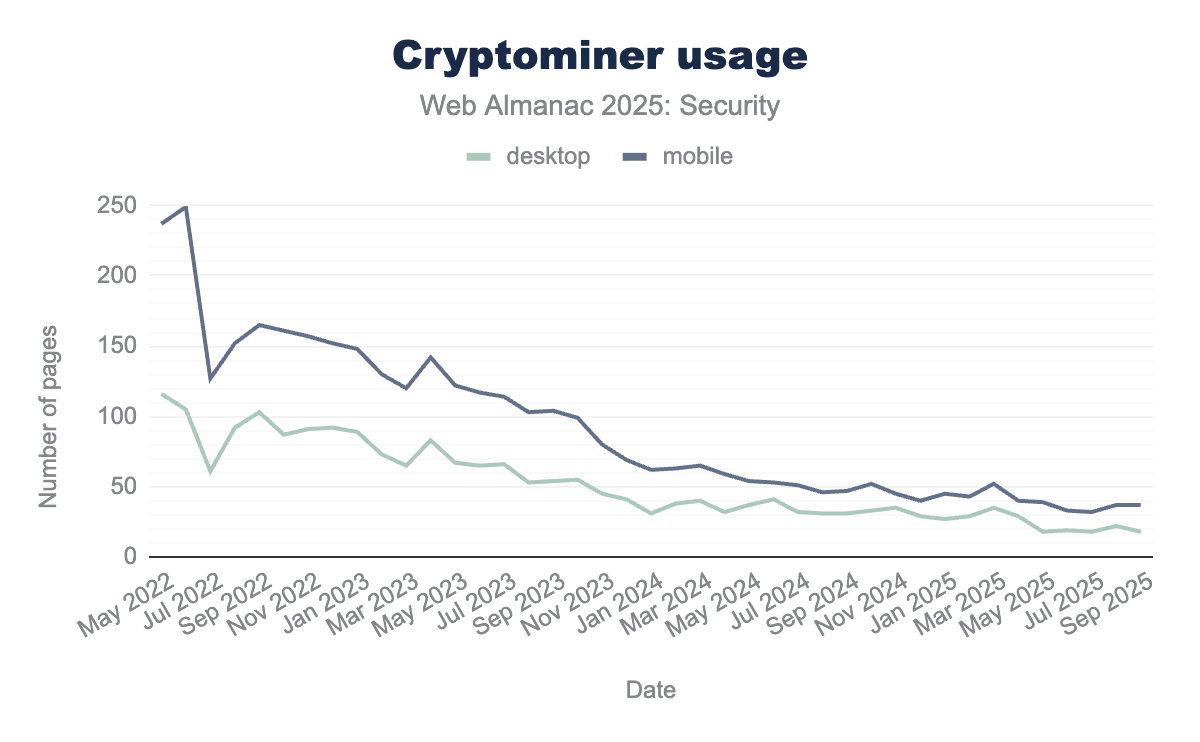

Cryptocurrencies are more popular than they have ever been. Cryptomining has been a large business for a number of years and adversaries have been known to install cryptominers as a form of malware on victim websites. Over the past years, the use of cryptominers on the web has been steadily declining.

We see the number of pages with cryptominers decreased to only 37 pages on mobile, a 42% decline since last year. It is also a 83% decline since September 2022, only three years earlier.

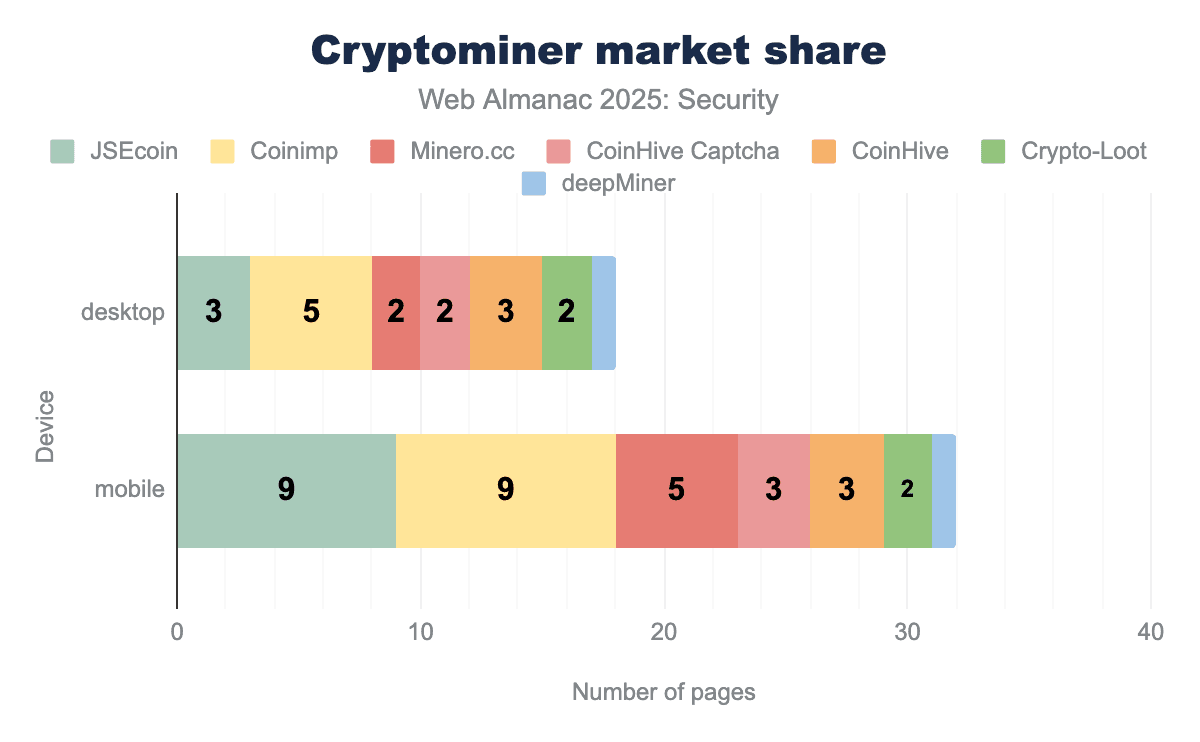

Although we find a very low absolute number of cryptominers on the web, we still take a look at the shares that different cryptominers represent. Compared to last year, we see the number of pages with Coinimp has dropped to match the nine pages that have JSEcoin. An interesting note to make is the difference between the number of cryptominers on desktop and mobile pages, with the number of pages on mobile being almost double the number on desktop.

Security misconfigurations and oversights

While there are many security mechanisms available on the web and in browsers, it is vital to configure these mechanisms correctly and as expected. Misconfigured security mechanisms create a false sense of security for the developer that thinks their users are protected. In this section we highlight the occurrence of several misconfigurations that can compromise a website’s security.

Unsupported policies in <meta>

When configuring security policies, it is important that developers understand how they have to define the policy. Some policies can be defined through both a header and the HTML <meta> tag. However, many policies cannot be defined through <meta>. Developers sometimes make the mistake of trying to configure these policies through the <meta> tag anyway. Unfortunately browsers will ignore these policies, resulting in inactive security policies.

| Policy | Desktop | Mobile |

|---|---|---|

X-Frame-Options |

4,584 | 5,564 |

X-Content-Type-Options |

2,440 | 2,854 |

Permissions-Policy |

1,983 | 2,236 |

X-XSS-Protection |

1,691 | 1,702 |

Referrer-Policy |

1,630 | 1,644 |

<neta>

We find that around 0.11% of mobile sites attempt to set security headers that browsers explicitly do not support via <meta> tags. The most frequently attempted policies are X-Frame-Options, X-Content-Type-Options and Permissions-Policy. Compared to 2024, we see that the number of mobile sites setting these policies in <meta> rose in absolute numbers by more than 5,000 pages, showing that these misconfigurations are still actively being set by developers.

Unsupported CSP directives in <meta>

While CSP can be configured via <meta> tags and this behaviour has been observed on 0.59% of mobile pages, certain CSP directives are explicitly disallowed in <meta> tag implementations and will be ignored by browsers. These directives can only be set by using the Content-Security-Policy response header.

| Directive | Desktop | Mobile |

|---|---|---|

frame-ancestors |

2.37% | 2.11% |

sandbox |

0.004% | 0.003% |

<meta> with disallowed directives

We find that over 2% of mobile pages setting a CSP policy via a <meta> tag include the frame-ancestors directive and 0.003% include the sandbox directive. The latter boils down to only three pages out of the entire crawled dataset. Compared to last edition, the misconfiguration of frame-ancestors shows up on 600 more pages, thereby rising by over 0.8%. This represents a slow but negative evolution for these types of misconfigurations.

COOP/COEP/CORP confusion

Because the cross-origin policies COEP, CORP, and COOP have a similar naming and are related in purpose, they are sometimes confused by developers. Assigning the wrong values to these headers has the effect that the browser will apply the default policy for the header as if no header was supplied at all, thereby disabling additional defenses wanted by the developer.

| Invalid COEP value | Desktop | Mobile |

|---|---|---|

same-origin |

4.43% | 4.02% |

cross-origin |

0.55% | 0.46% |

* |

0.13% | 0.11% |

(unsafe-none|require-corp); report-to='default' |

0.09% | 0.11% |

: require-corp |

0.09% | 0.10% |

In total, 5.6% of the observed COEP headers contain an invalid value on mobile. Over 4% of these headers contain the same-origin value that is only a valid value for the CORP or COOP headers. Another almost 0.5% contain cross-origin, a value destined for the CORP header. Unfortunately, these misconfigurations also saw a rise since last year, by almost 1% for the same-origin value in the COEP header.

In addition to these misconfigurations, we also observed several values with syntactical errors that the browser will not be able to parse and therefore will also revert to the default value for the header. These syntactical errors represent a minority of cases.

Timing-Allow-Origin Wildcards

The Timing-Allow-Origin (TAO) response header allows a server to specify a list of origins that can access values of attributes obtained through features of the Resource Timing API. Any origin listed in this header can thus access detailed timestamps relating to the connection to the server, such as the time at the start of the TCP connection, start of the request, and start of the response. Granting origins this access should be done with care, as this opens up the possibility for the listed origins to execute timing attacks or other cross-site attacks against the website.

In a case when CORS is configured, many of these types of timing values (including those listed above) are returned as 0 to prevent cross-origin leaks. By listing an origin in the Timing-Allow-Origin header, these values retain their original value and are no longer zeroed out.

Timing-Allow-Origin headers that are set to the wildcard (*) value.

Besides returning a list of origins, developers can also set the Timing-Allowed-Origin header’s value to the wildcard character * to indicate that any origin may access the timing information. We find that 84.6% of the TAO headers contain the wildcard * value, rising by 2% since last year. This indicates that many developers have no problem with universally exposing finegrained timing information to any origin.

Missing suppression of server information headers

When websites publish excessive information about their infrastructure, such as the server and specific version thereof, they may run a higher risk of being targeted by automatic vulnerability scanners. Hiding this information is a form of security by obscurity which is a tactic that is generally frowned upon because it does not address the core vulnerability of a system, however because it may aid in remaining under the radar of certain attacks we include an analysis.

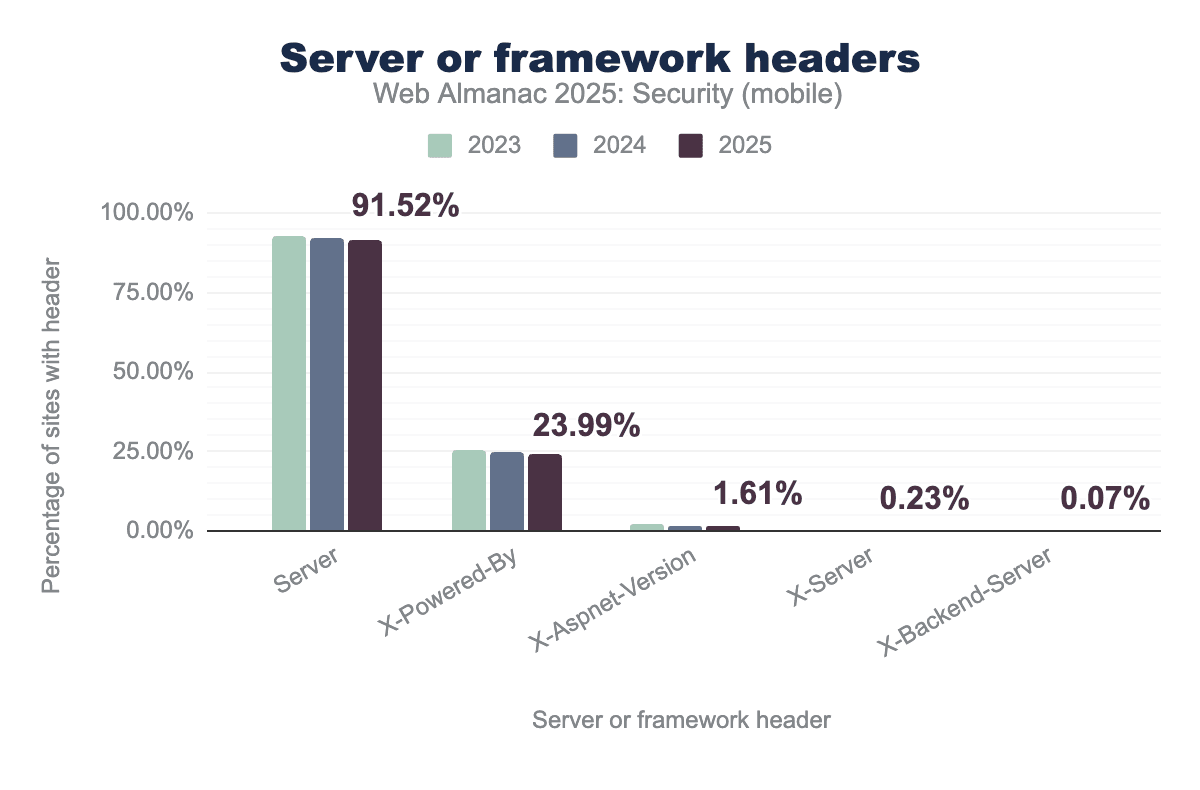

We track the use of headers that are commonly used to report this type of information, namely: Server, X-Server, X-Backend-Server, X-Powered-By, and X-Aspnet-Version.

Server header remains nearly universal, appearing on 91.52% of sites in 2025, while the X-Powered-By header is used by 23.99%. Other specialized headers like X-Aspnet-Version, X-Server, and X-Backend-Server show much lower usage, with all categories demonstrating a slight but consistent downward trend over the three-year period.Just like the past years, the Server header remains the most widely used header by a large margin over X-Powered-By. These headers show up on 91.5% and 23.9% of hosts on the web. For each of the headers we see a slight decrease in the amount of hosts they show up on. We don’t expect these values to see major changes over time, as many web technologies automatically set some of these headers and developers may not have a lot of interest in removing these headers as the gains in terms of security are small.

| Header value | Desktop | Mobile |

|---|---|---|

PHP/7.4.33 |

9.54% | 9.98% |

PHP/7.3.33 |

3.61% | 4.29% |

PHP/5.3.3 |

2.10% | 2.20% |

PHP/5.6.40 |

2.07% | 2.12% |

PHP/8.0.30 |

1.55% | 1.70% |

PHP/7.2.34 |

1.34% | 1.41% |

PHP/8.2.28 |

1.15% | 1.31% |

PHP/8.3.13 |

1.08% | 1.11% |

PHP/8.1.32 |

1.05% | 1.09% |

PHP/8.1.27 |

0.92% | 1.06% |

X-Powered-By header values with specific framework version

If we look at the most common values within the Server and X-Powered-By values, we see that PHP has the tendency to expose the exact version running on the server particularly in the X-Powered-By header. For both desktop and mobile, we find that over 27% of the X-Powered-By headers contain version information. It is likely that the header is automatically returned by the platforms that we observe in our data. Interestingly, we see a slight decrease in the old PHP versions 7.x and lower and a slight increase in the new PHP versions 8.x, which is an indication that at least some developers are updating their servers.

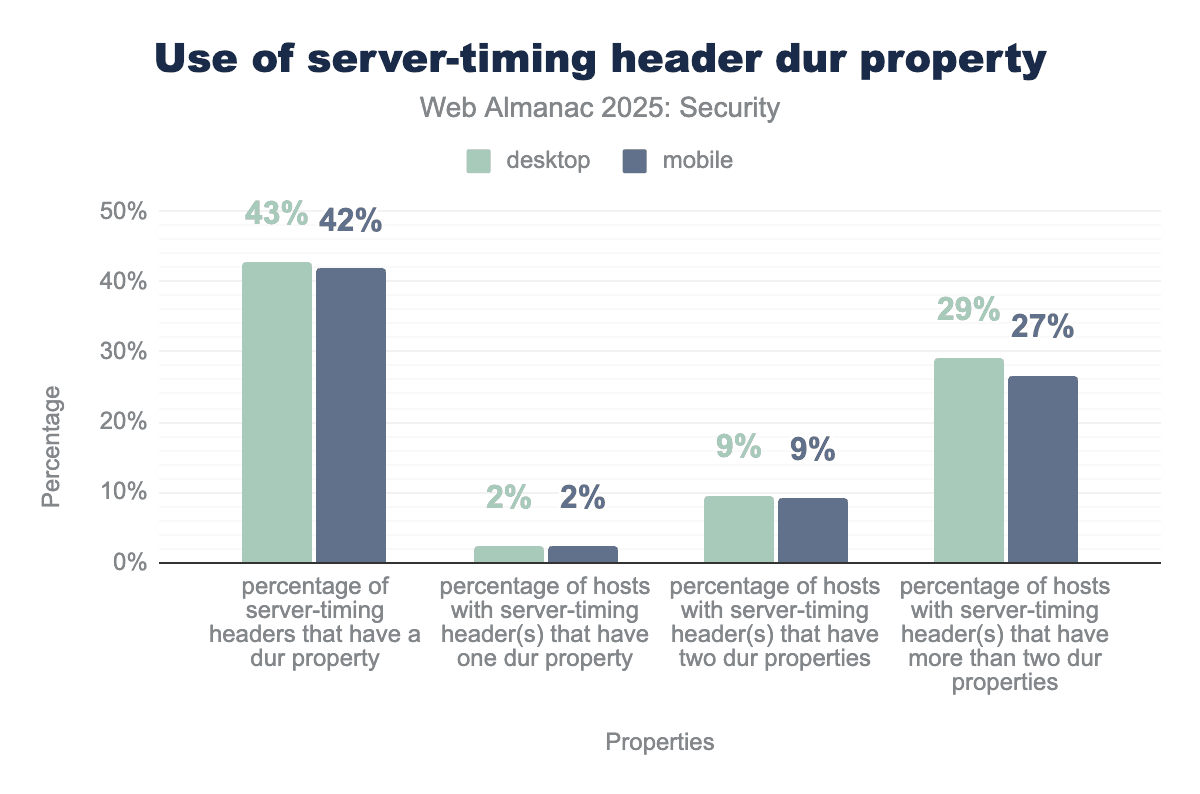

Missing suppression of Server-Timing header

The Server-Timing HTTP header is a response header defined in a W3C Editor’s Draft which can be used to communicate server performance metrics. Developers can send metrics containing zero or more properties. One of the specified properties is the dur property, which can be used to communicate millisecond-accurate timings that contain the duration of specific actions on the server.

Server-Timing header. When measured by unique hosts rather than individual responses, the adoption rate is slightly lower, with 21 percent of desktop hosts and 22 percent of mobile hosts utilizing the feature.Server-Timing header.

The percentage of hosts returning a server-timing header has increased by over 15% in use by over a fifth of hosts that have been visited by the crawler. This is a very steep increase since last year.

Server-Timing header across desktop and mobile platforms. The data indicates that a significant portion of these headers—43% on desktop and 42% on mobile—include at least one dur property. Furthermore, a substantial percentage of hosts (29% desktop, 27% mobile) expose more than two separate duration metrics.dur properties in Server-Timing headers.

Of the server-timing headers on the web, we find 42% of them have at least one dur property. This is a relative decrease compared to last year, but given the steep incline in header use over the year, the absolute number has risen. This also means that more headers do not include a dur property and use the header for other purposes, possibly through the use of the desc property that allows developers to set a description for certain metrics.

Because the information included in the server-timing header can be sensitive, access to the values is restricted to the same origin and to origins listed in the Timing-Allow-Origin header. As we have shown above, many websites configure the Timing-Allow-Origin with a wildcard character, allowing all origins to access this potentially sensitive information. Even without cross-origin access, timing attacks can still be executed directly against servers exposing sensitive timing information outside of the browser context.

Well-known URIs

Well-known URIs provide a standardized mechanism for designating specific locations for site-wide metadata and services. Defined by RFC 8615, a well-known URI is identified by a path component that begins with the prefix /.well-known/. This allows clients to discover specific resources without needing prior knowledge about a site’s URL scheme.

security.txt

The well-known security.txt file is a standardized file format that websites use to communicate vulnerability reporting information. White hat hackers and penetration testers can use this file to find contact details, PGP keys, policies, and other information for responsible disclosure.

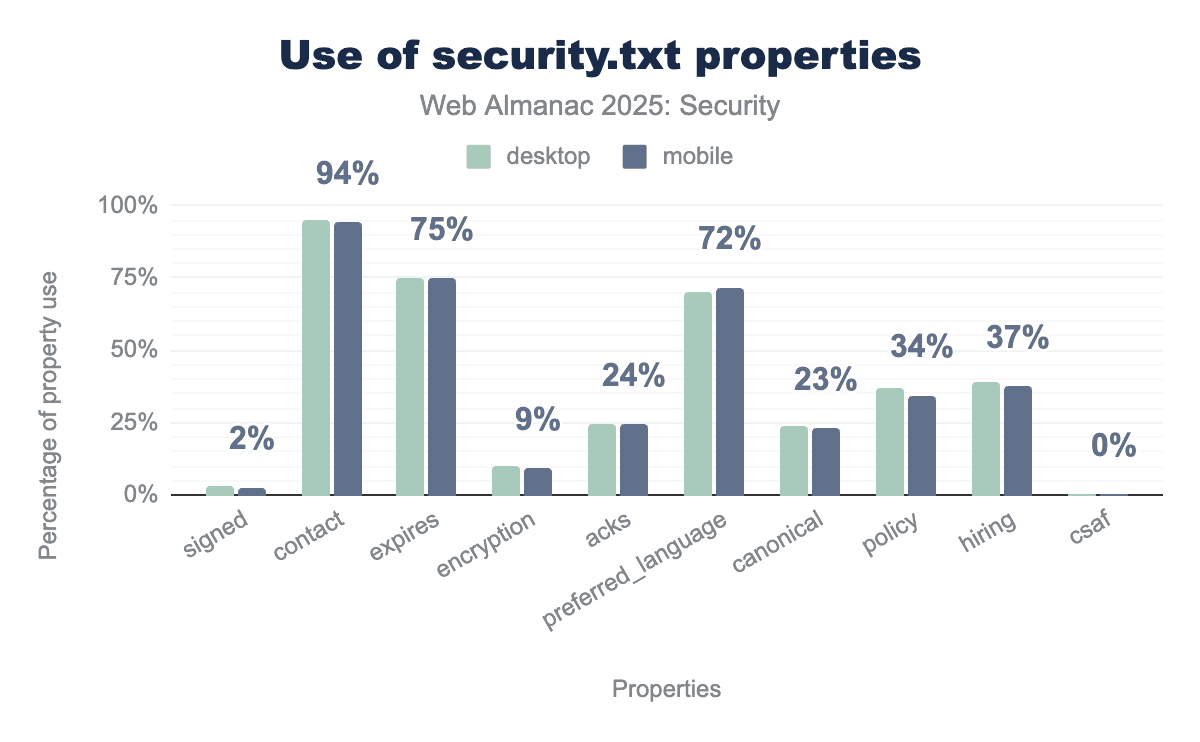

security.txt file on desktop and mobile platforms. The data shows that the mandatory contact field is the most widely adopted property, appearing in 94% of files, while the other required field, expires, is present in approximately 75% of implementations. Other common optional fields include preferred_language at 72% and hiring at 37%, while more technical or administrative properties like encryption (9%), signed (2%), and csaf (0%) see significantly lower usage. Overall, adoption rates are nearly identical between desktop and mobile devices.security.txt properties.

Adoption has increased to 1.82% of desktop and 1.72% of mobile websites, both up from 1% in 2024, showing growing recognition of standardized security disclosure practices.

Among sites implementing security.txt, contact information remains nearly universal at 95% (desktop) and 94% (mobile), up from 92% and 89% in 2024, respectively. Interestingly, 75% now define an expiry date, a significant jump from 51% for desktop and 48% for mobile websites in 2024. Preferred language is specified by 70-72% of implementations, while policy (which defines vulnerability reporting procedures) appears in only 37% desktop and 34% mobile files, down from 39% in 2024. However, the absolute number of security.txt files defining a policy has risen by two thirds.

This analysis shows that at least 25% of security.txt files are not fully valid, because including an expiry date along with contact information is required, as stipulated in RFC 9116.

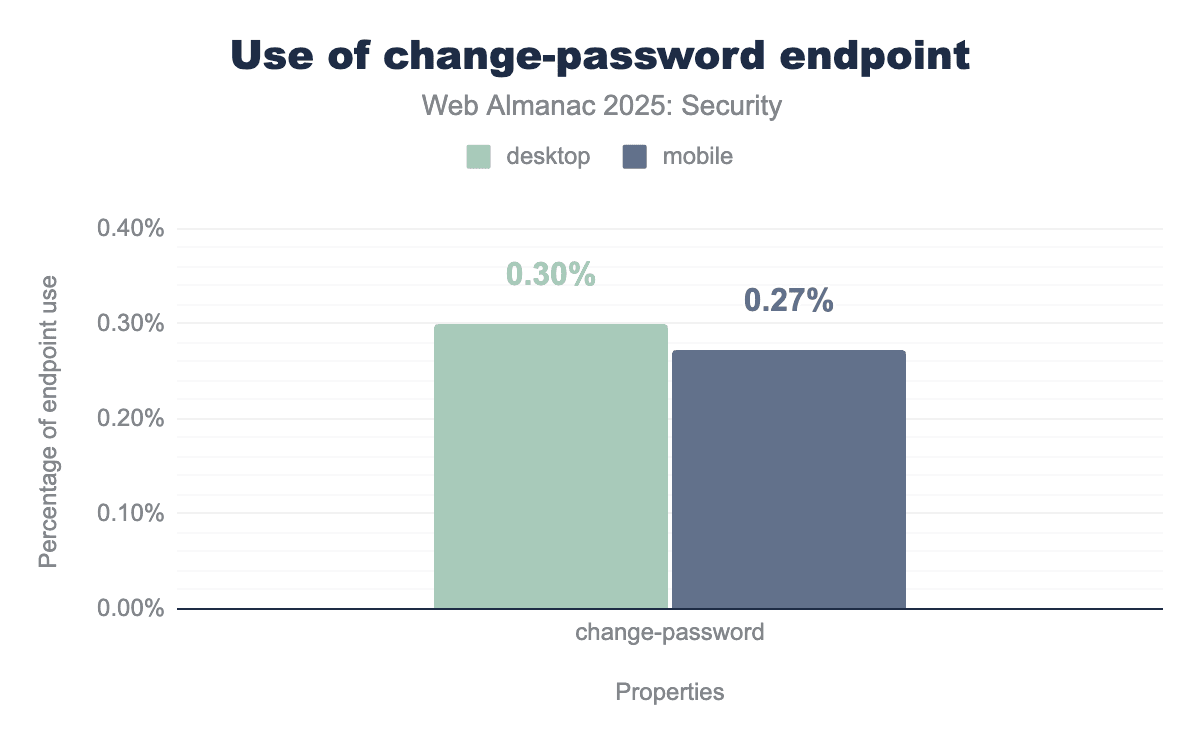

change-password

The change-password well-know URI is a W3C specification draft from 2021, which has not been updated since. The purpose of the URI is for users and external resources to quickly find the correct location at which they can change their passwords for the specific site.

/.well-known/change-password redirect on desktop and mobile platforms. The data reveals very low adoption rates for this feature, with only 0.30% of desktop sites and 0.27% of mobile sites currently utilizing the endpoint.We see a very minor rise to 0.30% in desktop sites (up from 0.27%) and no change for the mobile endpoints, which remain at 0.27%. This slow adoption is not unexpected, especially taking into account that not all websites require authentication mechanisms.

Detecting status code reliability

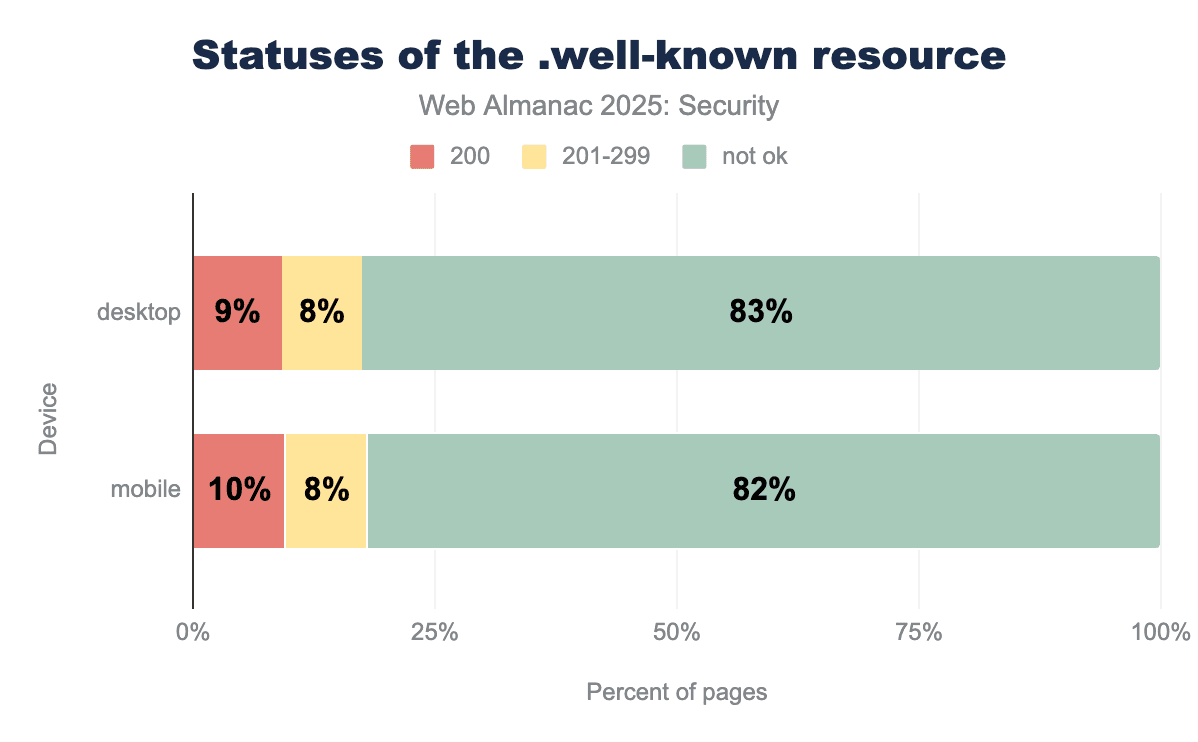

The specification draft to check on the reliability of a website’s HTTP response status code also remains unchanged since 2021. The purpose of this specific well-known endpoint is that it should never exist and thus the response status code should never be an ok status. If a redirect occurs after which the site responds with an ok status, this would be considered as incorrect behavior.

.well-known URI prefix used for consistent metadata discovery across web servers. The data shows that the overwhelming majority of these requests—83% on desktop and 82% on mobile—result in a "not ok" status, indicating that the intended resource could not be successfully retrieved or found. In contrast, successful 200 OK responses account for only about 10% of total requests, while status codes in the 201-299 range comprise an additional 8%..well-known endpoint to assess status code reliability.

We find similar results to 2022’s and 2024’s edition of the Web Almanac. However, the number of faulty ok status responses has grown slightly, from 84% in 2024 for both desktop and mobile pages to 83% and 84%, respectively. Web developers should continue to make their application use the correct status codes to respond to incoming requests in order to avoid these status codes from losing meaning.

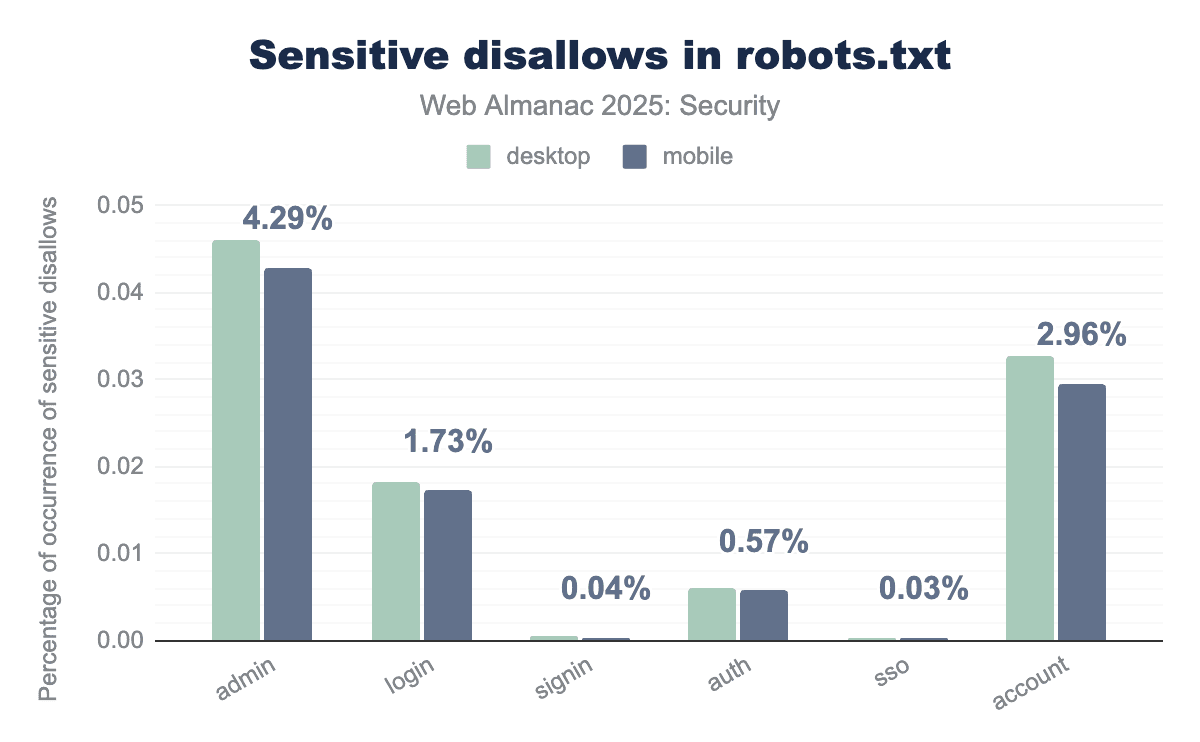

Sensitive endpoints in robots.txt

Finally, we check whether sensitive endpoints are disallowed to be visited by crawlers in the well-known robots.txt file. By checking the disallowed endpoints in this file, attackers may find pages to target. This year, 81% of desktop sites and 80% of mobiles sites hosted a robots.txt file, which is very similar to last year’s edition of the Web Almanac.

admin is the most frequently disallowed sensitive term, appearing in 4.29% of desktop robots.txt files, followed by account at 2.96%. Other terms such as login (1.73%) and auth (0.57%) are also commonly restricted, while signin and sso represent less than 0.05% of occurrences.robots.txt.

Also the contents of those files remain very similar. The largest increase is recorded for the auth endpoint with 0.2% for desktop sites, while the largest decrease was recorded for the login endpoint with 0.2% for desktop sites.

Conclusion

This security chapter shows positive trends in the adoption of web security policies. HTTPS is reaching near-100% adoption overall, and per-country metrics show every country is moving towards the goal of a universal use of HTTPS. We saw growing adoption of many modern security policies aiming to better protect users against modern attacks such as the Content-Security-Policy which saw an increase in use by over 18% and the Permissions-Policy which was used 50% more than last year. We also see newer policies like the Document Policy appear in the wild, showing that developers are actively working on adoption of new security features.

Despite these positive trends, developers must remain vigilant when leveraging these security mechanisms. Due to the growing complexity of the many available security mechanisms, we saw growth in the number of misconfigurations on the web. We saw that 0.1% of pages configure security policies in the <meta> HTML tag while this is not supported by browsers. Another problem is the confusion between related protections: 5% of values of the COEP header are invalid values that are only valid in the related CORP or COOP header. We also observe a form of developer fatigue where the least strict value of a protection is configured in order to make deployment more manageable or prevent potential problems, such as the wildcard value in the Timing-Allow-Origin header showing up in over 84% of these headers. Luckily, developers can easily mitigate these issues once they are aware of the problems.

New attacks in the future will inevitably drive the design of even more protection mechanisms to keep users safe worldwide. Policy makers will have to focus on reducing complexity in these new mechanisms to avoid developer confusion, but while the adoption of new security features takes time, we see relatively new policies being picked up and getting more adoption over time, thereby creating a more secure web for everyone.