WebAssembly

Introduction

WebAssembly (Wasm) has evolved from a web-centric optimization tool into a high-performance, universal bytecode format. Officially a W3C standard since 2019, the ecosystem reached a technical turning point with the release of Wasm Version 3.0 in December 2025. This version standardizes several advanced features—such as Garbage Collection, 64-bit address space, and Multiple Memories—allowing high-level languages like Java, Kotlin, and Dart to run natively and efficiently in both browser and standalone environments.

Methodology

We follow the same methodology from the 2021 Web Almanac, where WebAssembly was introduced for the first time.

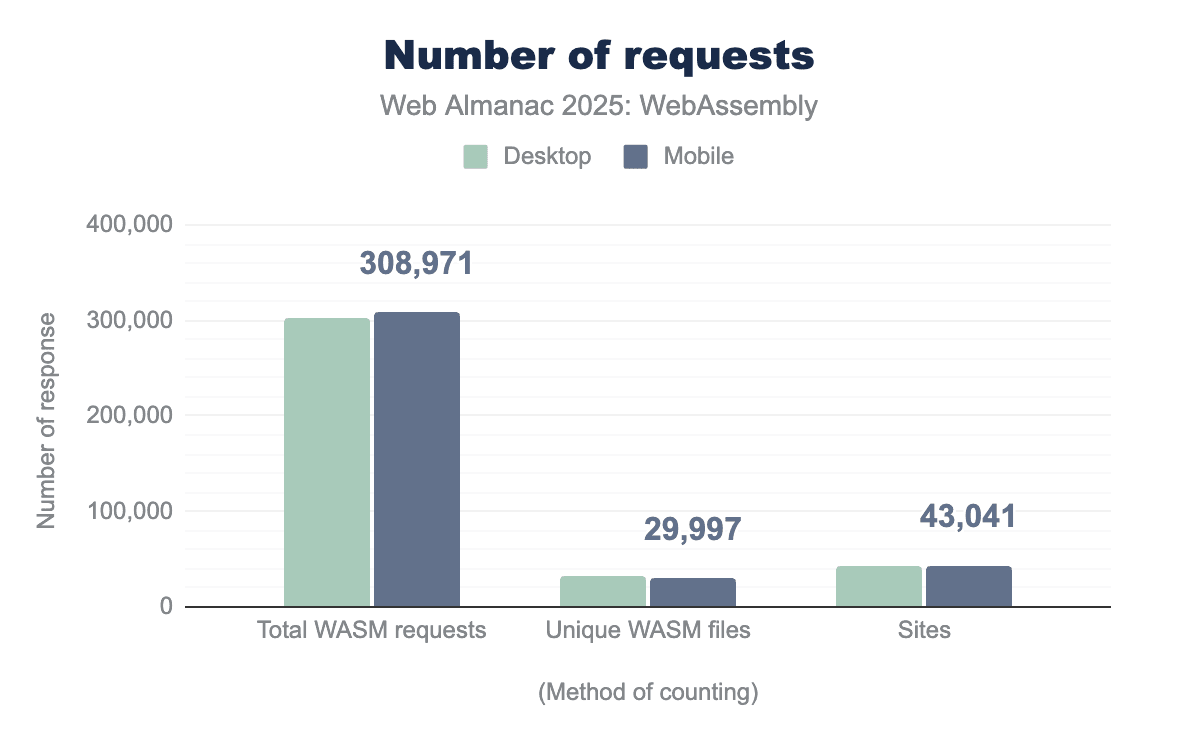

Data Collection: This chapter relies on this dataset provided by HTTP Archive July 2025 crawl data which is hosted on Google BigQuery to identify WebAssembly modules by matching the Content-Type (application/wasm) and the .wasm file extension. Using this method, we found at least one WebAssembly module on 43,000 sites, representing 0.35% of all sites analyzed.

Analysis: In addition to the HTTP Archive dataset, we use almanac-wasm-stats a tool to download and validate the WebAssembly modules identified from the HTTP Archive for local analysis. This tool extracts metadata from these downloaded files, allowing us to identify programming languages, libraries, and specific features used within the Wasm modules.

Limitations: Our tool almanac-wasm-stats focuses on static analysis of Wasm modules and does not execute them. Therefore, we cannot capture dynamic behaviors or runtime features that may be present during actual execution in a browser or standalone environment. Additionally, some Wasm modules may be obfuscated or minified, which can limit our ability to accurately identify their characteristics. We have enhanced (wasm-stats) and implemented below features in almanac-wasm-stats that helps in language usage analysis.

- It can take inputs in url and respective user-agent strings that improves download task.

- Accept huge number of input in the format of BigQuery’s JSONL result.

- Validate Wasm and provide insights with Binary Toolkit that helps to improve stats (ref. wasm2wat)

- Run and Trace tasks activities concurrently i.e. wasm file downloading, validating and populating stats.

-

Enhances language identifiers for old rust implementation (

wasm-stats) and added new languages : Scala, Dotnet/Mono, Go & TinyGo, TeaVM based languages, Kotlin; This reduces the language usage : “Unknown” numbers and improves language stats. - Produce full Wasm language usage stats along with validation and download failures.

- Tool’s *lug-n-play architecture that helps to introduce new stats with WebAssembly Toolkit / SDK in JSON existing stats format for future enhancements.

WebAssembly usage

In this section, we present our results on the usage of WebAssembly on the web.

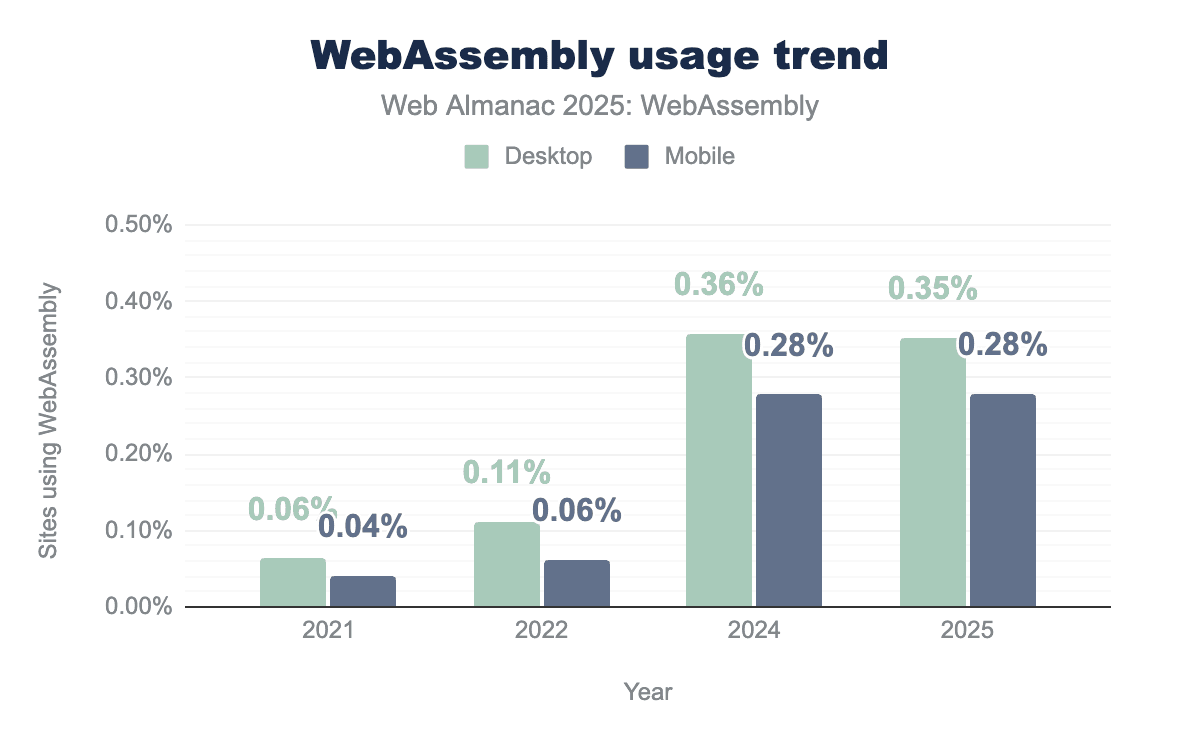

Year-on-year trend

We find that WebAssembly adoption has grown from 0.04% in 2021, although rates have remained consistent over the last two years. In 2025, we found WebAssembly modules on 0.35% of desktop sites and 0.28% of mobile sites, representing approximately 43,000 sites. Furthermore, mobile adoption was lower than desktop adoption in all observed years, averaging a 30% difference.

WebAssembly by rank

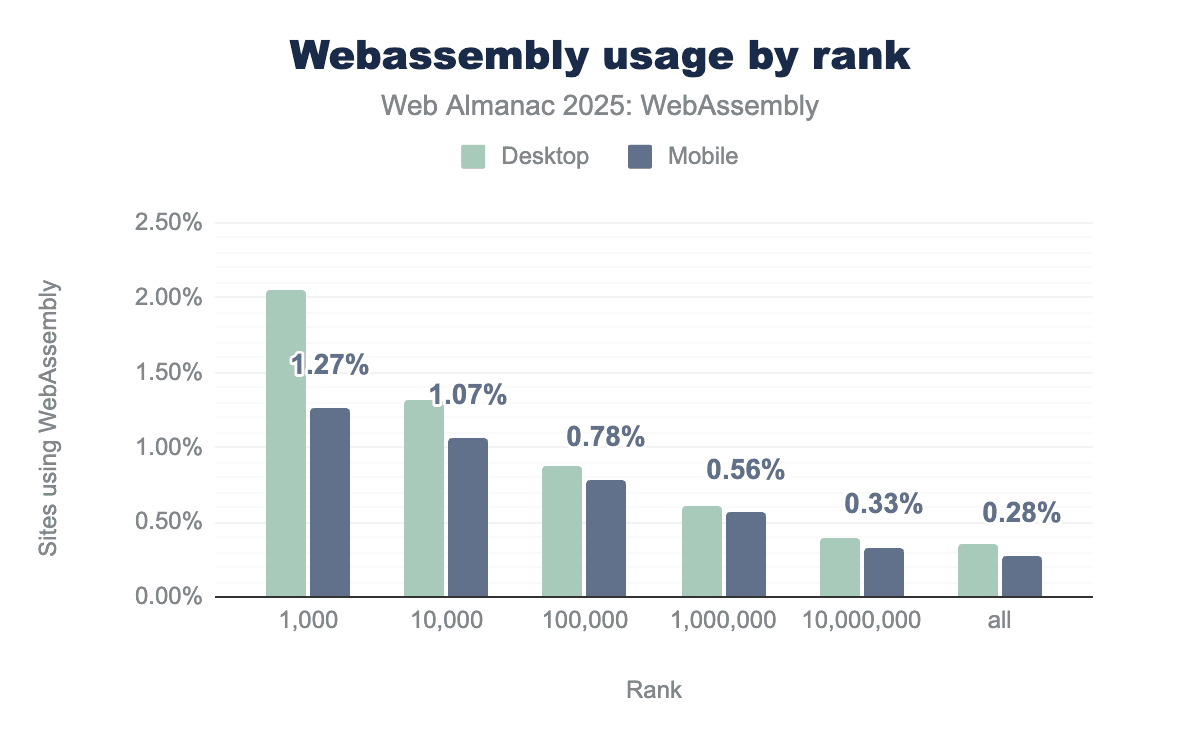

We see a strong correlation between site popularity and WebAssembly adoption. Usage is most concentrated among the top 1,000 websites, reaching 2% on desktop and 1.27% on mobile. These top-tier sites frequently host complex applications—such as design tools or heavy media editors—that require the high performance Wasm provides.

Adoption rates decrease as site rank declines, following a consistent distribution pattern. For sites outside the top 10 million, adoption is approximately 0.33% for desktop and 0.28% for mobile.

While desktop usage remains higher in the top ranking groups, the gap narrows significantly in the long tail, suggesting that for the majority of the web, WebAssembly is deployed as a cross-platform resource rather than being restricted to specific environments.

WebAssembly requests

Overall, we recorded 303,496 WebAssembly requests on desktop and 308,971 on mobile. Although more desktop sites utilize WebAssembly, the total volume of requests is slightly higher on mobile.

Furthermore, we identified 157,967 unique URLs on desktop and 165,870 on mobile. To estimate the number of unique binaries, we grouped modules by identical filename and response size. Using this method, we found 87,596 unique Wasm modules on desktop and 84,851 on mobile. These findings indicate that by name approximately 72% of WebAssembly requests serve duplicate modules, highlighting substantial reuse of libraries across the web.

MIME type

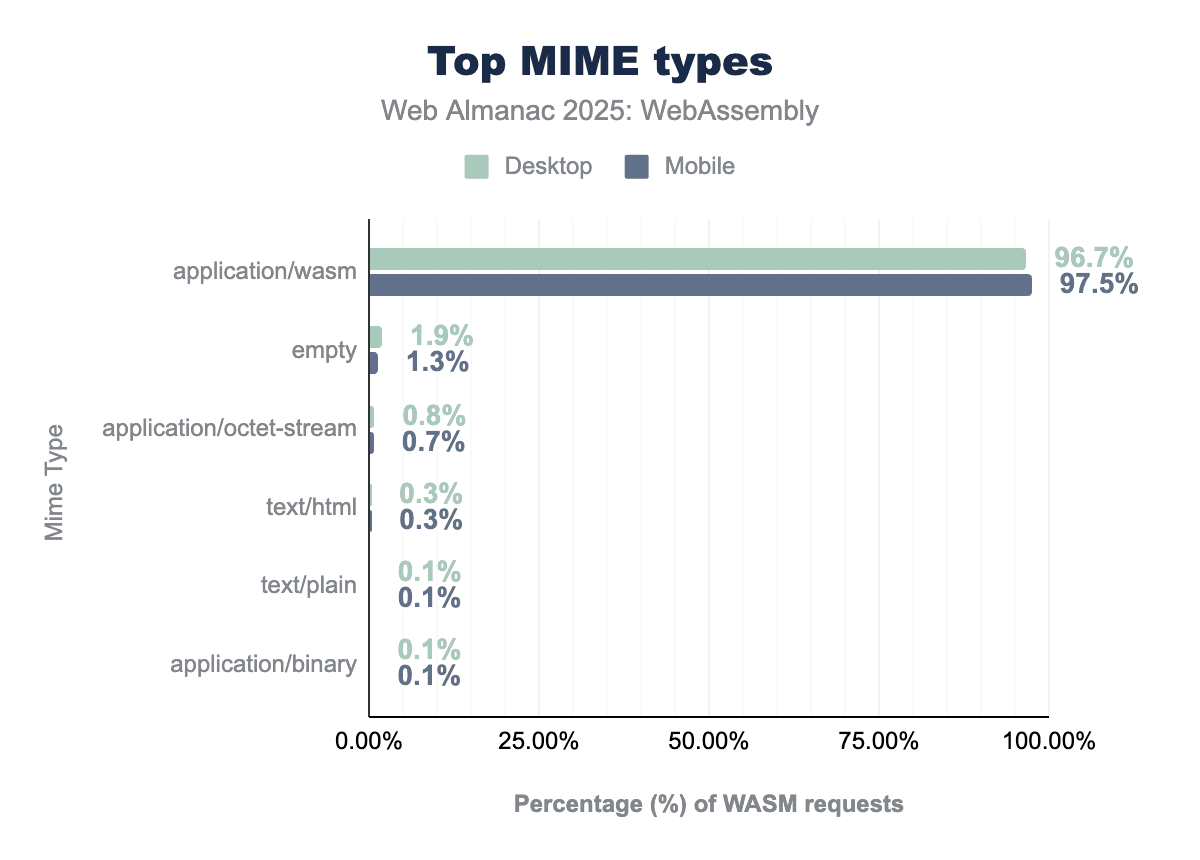

The application/wasm MIME type was identified in 293,470 desktop and 301,127 mobile requests. Instances of missing or incorrect MIME types (such as text/html or text/plain) were low, affecting 3.2% of desktop and 2.4% of mobile requests. These represent a significant decline compared to 2021, indicating improved awareness and adherence to proper server configuration.

Module size

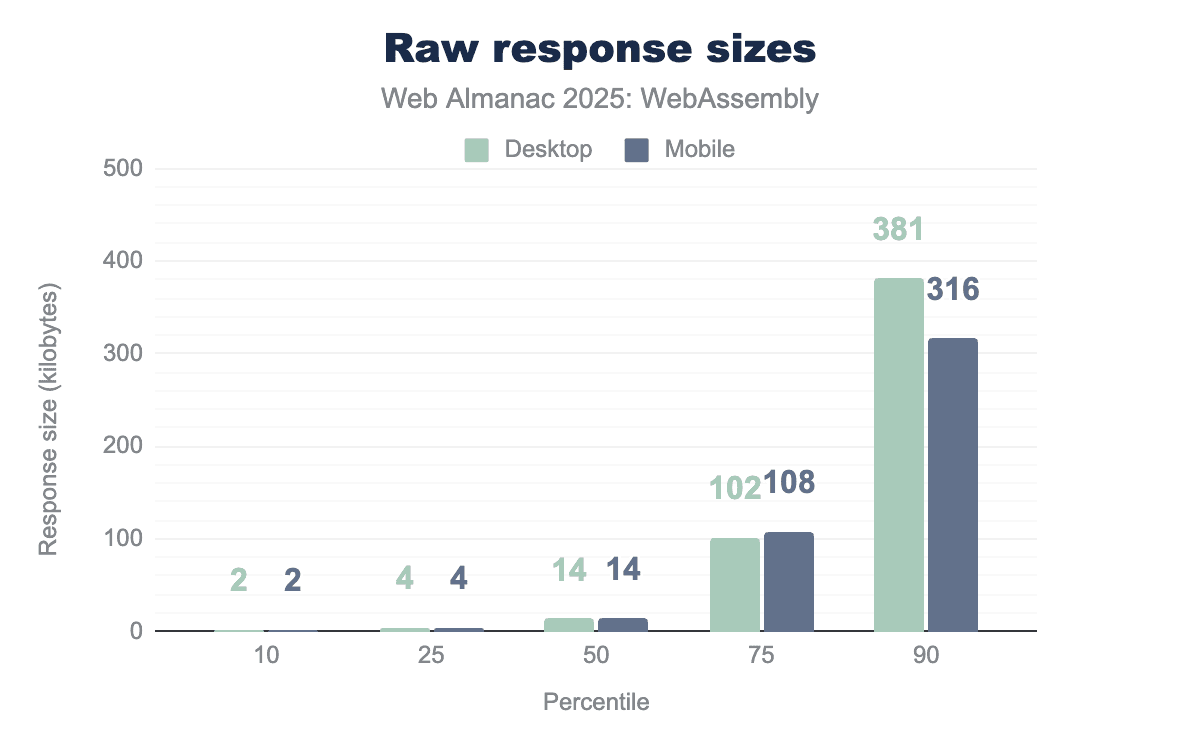

WebAssembly module sizes vary drastically based on their specific use cases. We observed that the bottom 50% of modules are quite small, ranging between 2 KB and 14 KB. These are typically “micro-utilities” like Base64 encoders or checksum calculators, often written in AssemblyScript or Rust to handle performance-critical tasks where JavaScript lacks precision.

Conversely, at the 90th percentile, sizes increase significantly to 381 KB on desktop and 316 KB on mobile. These larger binaries usually represent full desktop-grade applications ported to the web—such as Adobe Photoshop or Google Earth—compiled from heavier languages like C++ or C# to handle complex 3D rendering and logic.

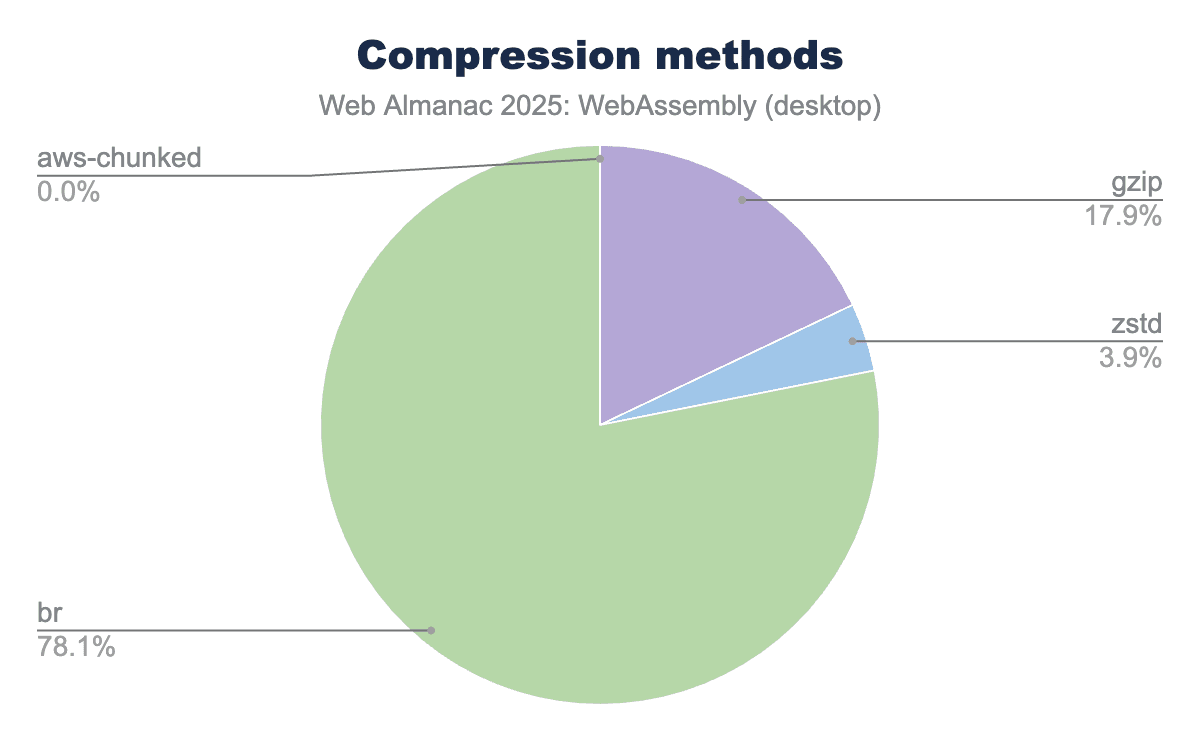

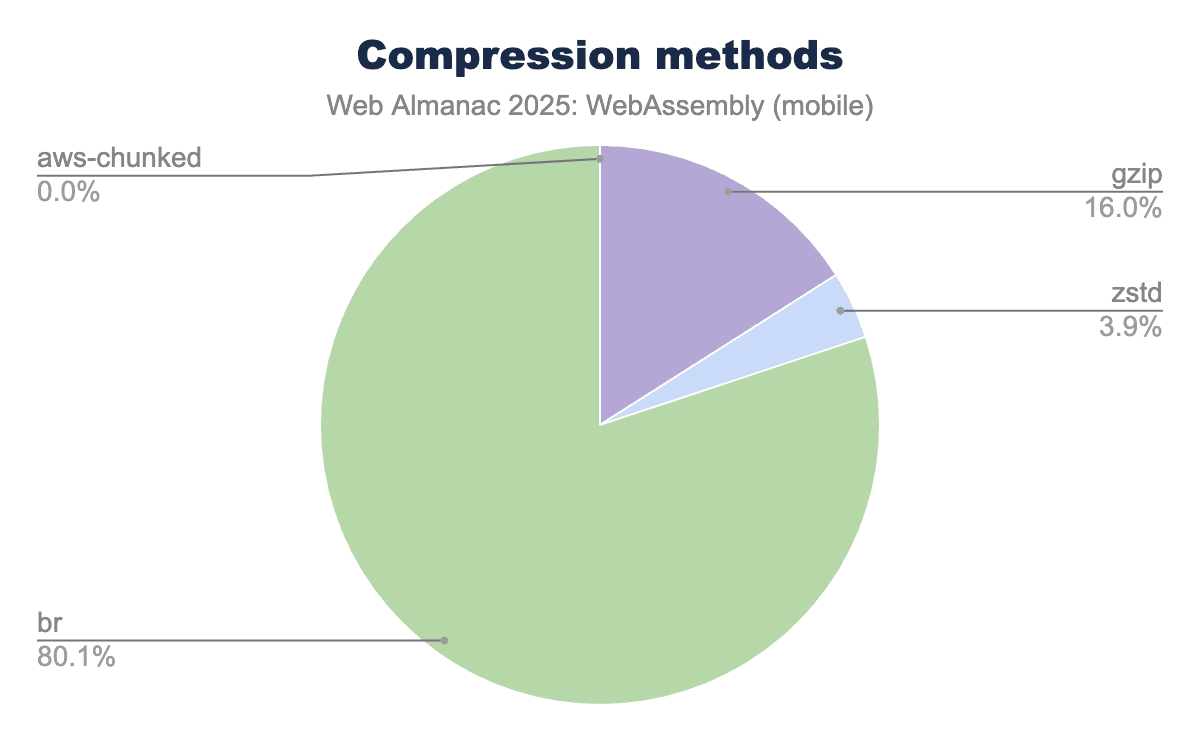

The above chart shows the size of response body size, It is often called as “raw response size” that measures only the raw, often decoded—the data payload that client received. It represents the size of the resource itself. However as per the research and common practices for Wasm deliverables, Wasm modules are compressed and optimized with various tools like Brotli and also transfered over network to the client with compression methods like gzip, br, zstd along with Content-Encoding headers.

Interestingly, If we see performance benchmarks” activities by various communities from past couple of years, the compression methods ’br’ and ’zstd’ usage awareness are increasing and it shows continuous evolution and adoption by the developers and by the cdn providers.

Beyond these standard distributions, the dataset contains significant outliers. The largest single WebAssembly module identified measured 234 MB on desktop and 170 MB on mobile, indicating the deployment of large-scale client-side applications.

Interestingly If we think about JS deliverables are in MB size often but Wasm deliverables are in quit smaller size this is because JS is the human readable, high level source code, while bytecode is a low level, intermediate representation of the code that is machine agnostic.

we know the modern JS engines, such as Google’s V8, convert JS source code into bytecode internally as part of the execution process; this shows the bytecode’s efficiency compare to JS’ in small size.

WebAssembly libraries

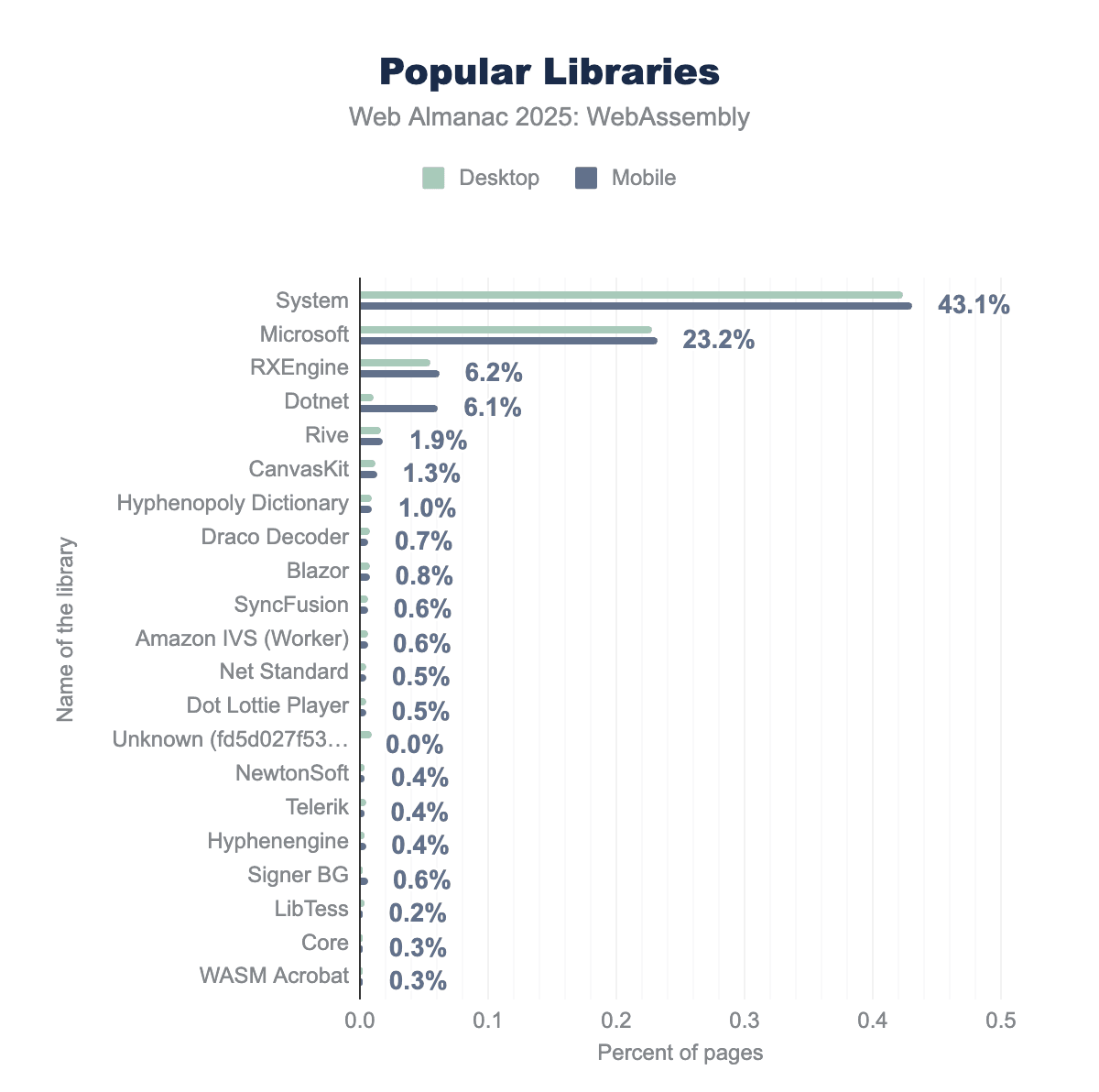

Next, we analyze the import names within WebAssembly binaries to understand the most popular underlying libraries and frameworks in the ecosystem.

We find that System (43%), Microsoft (23%), RXEngine (6%), and Dotnet (6%) are the most popular libraries or frameworks used in WebAssembly modules, indicating Microsoft’s dominance within this ecosystem, driven specifically by the Dotnet and Blazor frameworks.

Microsoft has various WebAssembly libraries and framework for functionality of System utilities, Identity, Networking, Storage, Json and many more for reusable libraries. By combining those libraries and framework(s), Microsoft eco system for WebAssembly covers 78.8% and 79.3% respectively for desktop and mobile client.

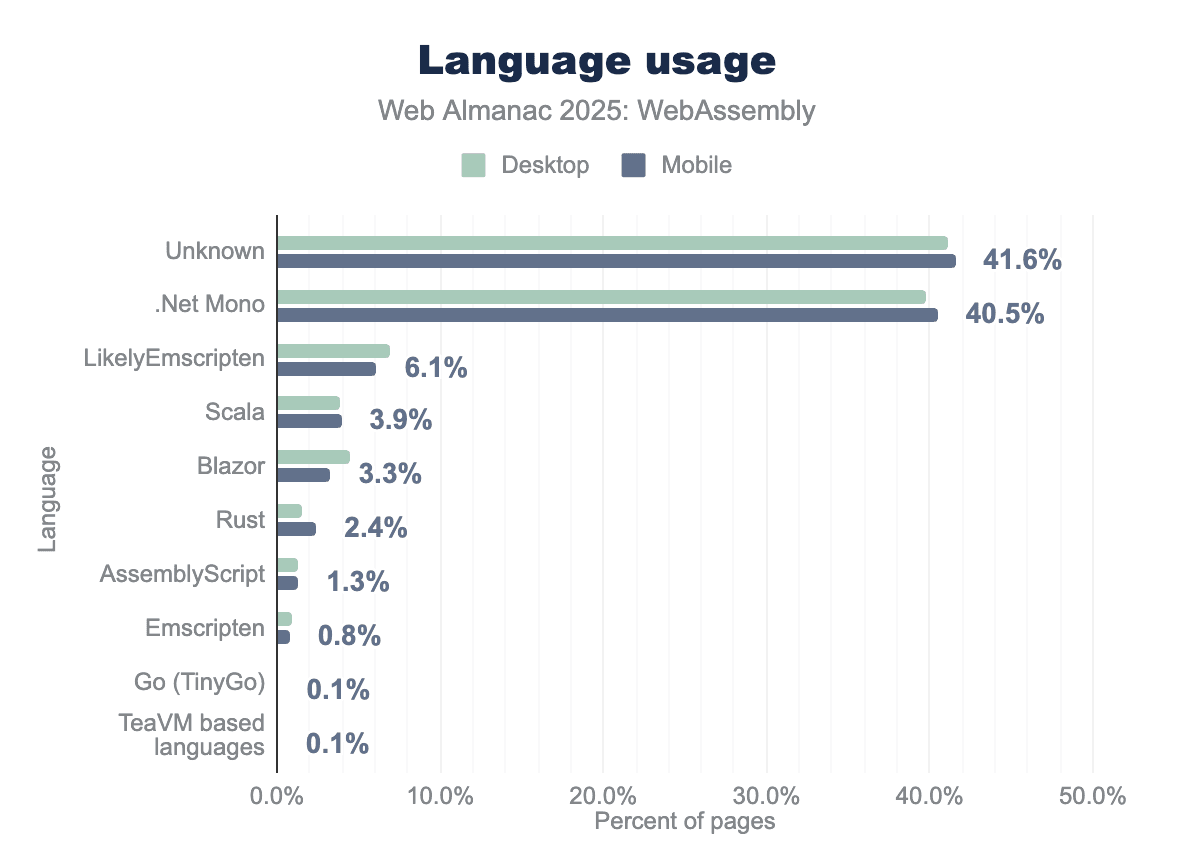

WebAssembly languages

WebAssembly can be developed using various languages, including C++, C#, and Ruby. With the introduction of Wasm 3.0, the range of supported languages has extended to include examples such as Java, Scala, Kotlin, and Dart. In this section, we provide an overview of the languages used to develop WebAssembly modules.

Our tool successfully identified the source languages for 64.3% of WebAssembly modules on desktop and 72.8% on mobile. The remaining (35.7% and 27.2%) could not be identified, primarily due to minification(the stripping of metadata), webassembly validation or download failures.

Among the identified languages, .NET/Mono + Blazor is the most common, holding a 41.7% share on desktop and 38.7% share on mobile. Although minified export/import names often obscure the source language, the Emscripten (C++) toolchain uses a distinctive naming convention. This allows us to attribute these modules with confidence, finding that Emscripten accounts for 10.1% of usage on desktop and 7.8% of usage on mobile, followed by Scala at 3.6%(on desktop) and 3.4%(on mobile) usage.

Together with our findings on library usage, these results underscore the significant dominance of the Microsoft ecosystem within the WebAssembly landscape.

WebAssembly features

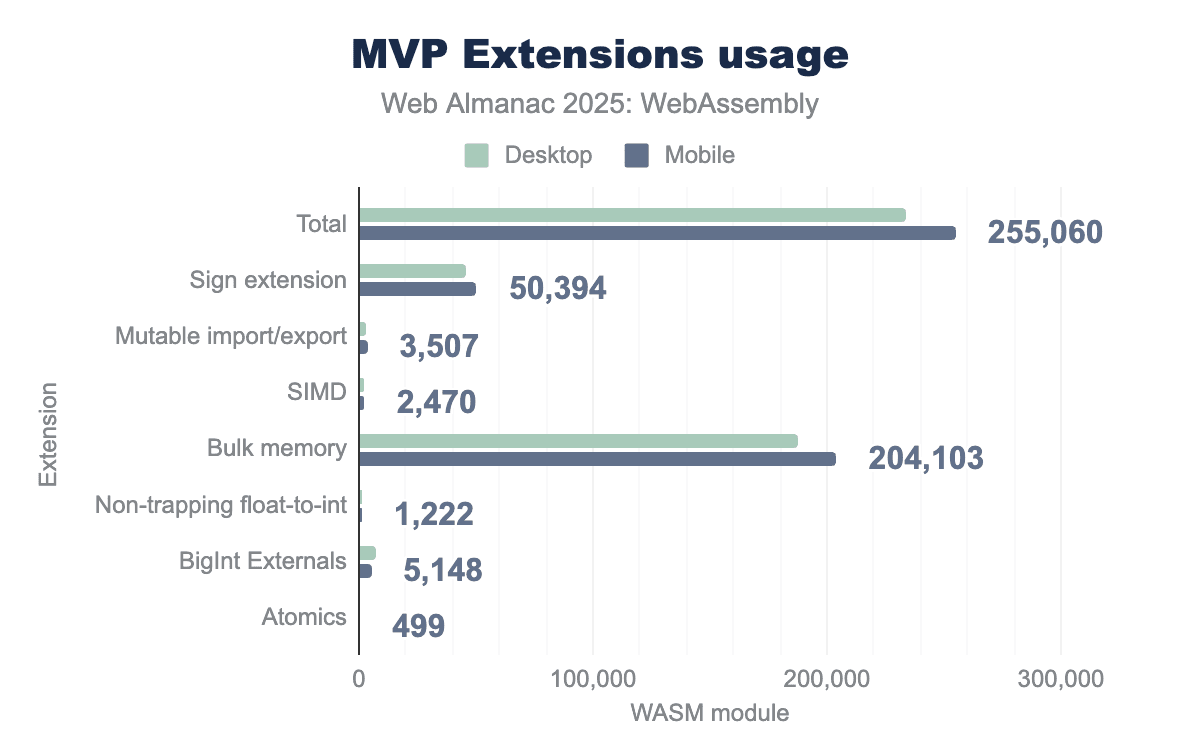

In this section, we analyze the usage of post-MVP (Minimum Viable Product) WebAssembly features. While we acknowledge that the features discussed here are limited and do not cover all the features WebAssembly supports, we believe highlighting the adoption of these features remains important. We encourage readers to contribute to the analysis tool used in this chapter to help track further features in the future.

We find that Bulk Memory is the most widely adopted feature, appearing in 187,674 desktop and 204,103 mobile modules. This feature improves performance by allowing efficient copying and initialization of large memory blocks, mirroring the efficiency of the native memcpy function in C. Furthermore, Sign Extension—which provides operators for extending integer values (such as extending an 8-bit integer to 32-bit)—is the second most popular feature, found in 45,969 desktop and 50,394 mobile modules.

Conclusions

WebAssembly adoption has significantly increased over the last four years, rising from 0.04% in 2021 to 0.35% in 2025, though growth has stabilized in the last two years. Usage is most prevalent on high-ranking websites and decreases significantly among less popular pages. We find that WebAssembly is currently deployed for two distinct purposes: handling specific utility functions (such as encryption or checksums) and powering full standalone applications. Furthermore, our findings highlight the widespread adoption of Microsoft’s frameworks, indicating their significant role in driving the current WebAssembly ecosystem.

Considering the significant developments in Wasm specifications and increased interest from the community, we believe the adoption of WebAssembly will further increase in the future.