CDN

Introduction

A Content Delivery Network (CDN) is a geographically distributed network of proxy servers in data-centers. The goal of a CDN is to provide high availability and performance for web content. It does this by distributing content closer to the end users.

CDNs have been in existence for over two decades. With the exponential rise in internet traffic contributed by online video consumption, online shopping, and increased video conferencing due to COVID-19, CDNs are required more than ever before. They ensure high availability and good web performance despite this growth in internet traffic.

During the early days, a CDN was a simple network of proxy servers which would:

- Cache content (like HTML, images, stylesheets, JavaScript, videos, etc.)

- Reduce network hops for end users to access content

- Offload TCP connection termination away from the data centers hosting the web properties

They primarily helped web owners to improve the page load times and to offload traffic from the infrastructure hosting these web properties.

Over time, the services offered by CDN providers have evolved beyond caching and offloading bandwidth/connections. Now they offer additional services such as:

- Cloud-hosted Web Application Firewalls

- Bot Management solutions

- Clean pipe solutions (Scrubbing Data-centers)

- Serverless Computing offerings

- Image and Video Management solutions etc.,

Thus, a web owner these days has a lot of options to choose from. This can be overwhelming and complex since these new offerings from CDNs make them an extension of your application and require closer integration with application development life-cycles.

There are benefits to web owners in pushing web application logic and workflows closer to the end user. This eliminates the round trip and bandwidth that a HTTP/HTTPS request would take. It also handles near-instant scalability requirements for the origin. A side-effect of this is that Internet Service Providers (ISPs) benefit from the scalability management as well, which improves their infrastructure capacities.

This reduction in requests reduces the load on the internet backbone, (read Middle-Mile of the Internet). It also helps manage more of the internet load within the last mile of the internet. Thus, a CDN plays a multifaceted role in the Internet landscape as it allows web owners to improve the performance, reliability and scalability of content delivery.

Caveats and disclaimers

As with any observational study, there are limits to the scope and impact that can be measured. The statistics gathered on CDN usage for the Web Almanac are focused more on applicable technologies in use and not intended to measure performance or effectiveness of a specific CDN vendor. While this ensures that we are not biased towards any CDN vendor, it also means that these are more generalized results.

These are the limits to our testing methodology:

-

Simulated network latency: We use a dedicated network connection that synthetically shapes traffic.

-

Single geographic location: Tests are run from a single datacenter and cannot test the geographic distribution of many CDN vendors.

-

Cache effectiveness: Each CDN uses proprietary technology and many, for security reasons, do not expose cache performance.

-

Localization and internationalization: Just like geographic distribution, the effects of language and geo-specific domains are also opaque to these tests.

-

CDN detection: This is primarily done through DNS resolution and HTTP headers. Most CDNs use a DNS CNAME to map a user to an optimal datacenter. However, some CDNs use Anycast IPs or direct A+AAAA responses from a delegated domain which hide the DNS chain. In other cases, websites use multiple CDNs to balance between vendors, which is hidden from the single-request pass of our crawler.

All of this influences our measurements.

Most importantly, these results reflect the utilization of specific features (Example: TLS, HTTP/2 etc.,) per site, but do not reflect actual traffic usage. YouTube is more popular than “www.example.com” yet both will appear as equal value when comparing utilization.

With this in mind, here are a few statistics that were intentionally not measured in the context of a CDN:

- Time To First Byte (TTFB)

- CDN Round Trip Time

- Core Web Vitals

- Cache Hit versus Cache Miss performance etc.

While some of these could be measured with HTTP Archive dataset, and others by using the CrUX dataset, the limitations of our methodology and the use of multiple CDNs by some sites, will be difficult to measure and so could be incorrectly attributed. For these reasons, we have decided not to measure these statistics in this chapter.

CDN adoption

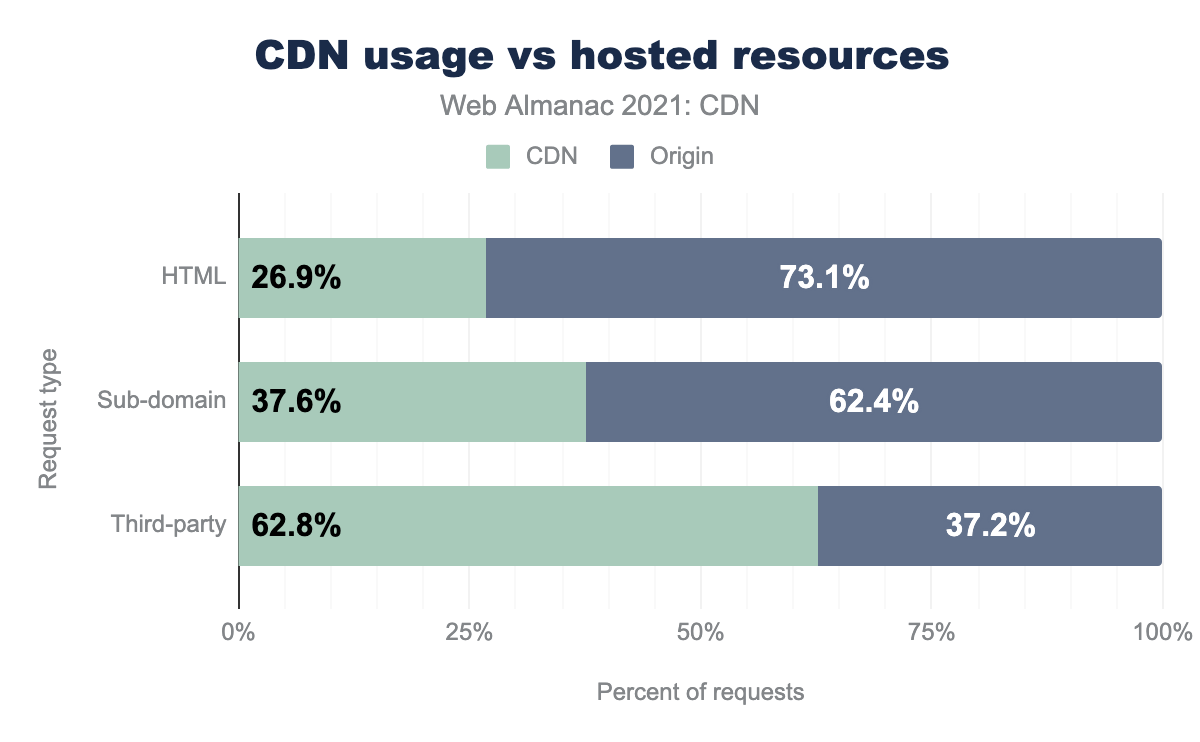

The contents in a web page can be divided into 3 parts, namely:

- Base HTML page (e.g.,

www.example.com) - Embedded first-party content on subdomains (e.g.,

images.example.com,css.example.cometc.) - Third-party content (e.g., Google Analytics, Advertisements etc.)

From their inception, CDNs have been the go-to solution for delivering embedded content such as images, stylesheets, JavaScript, and fonts. This kind of content doesn’t change frequently, making it a good candidate for caching on a CDN’s proxy servers.

With the evolution of CDN technology an expressway was set up on the internet for non-cacheable assets. This means the main web page and APIs can now be delivered reliably and faster, compared to a TCP connection to the origin.

The impact of this can be seen in the above chart when we compare this against the same data in 2019 chapter (note, there was no CDN chapter in 2020 Web Almanac). It’s good to see the trend of sites using CDN has improved by 7% between 2019 and 2021. This shows that more of the industry is leveraging CDNs to take benefit of consistent content delivery times and minimize the impact of congestion on Internet.

Looking at third-party content, there is negative growth for CDN adoption. Compared to 2019 chapter, we see 3% reduction in domains using CDNs. Third-party domains are used by SaaS vendors for analytics, advertisements, responsive pages, etc. It is in the SaaS vendor’s interest to use CDNs for their services. Their content is used by multiple web owners and this content gets accessed by end users across geographies, making CDNs necessary from both a business and performance standpoint. This is evident in the charts where it’s clear that third-party content has the highest adoption of CDN.

But why do we see this negative growth in CDN Adoption for third-party domains?

The probable reasons for this include:

- The HTTP/2 protocol requires web owners to consolidate the domains instead of using multiple domains for optimal performance

- Contribution of third-party content to total page weight has also increased over the years (refer to the Third Parties chapter for more details) leading to increased page load time concerns for web owners

- Customization/personalization of third-party scripts to suit the requirements of web owners

These changes have led to the SaaS vendors offering “self-hosting” options to web owners. This leads to more content being delivered over the first-party domain instead of the vendor’s domain. When this happens, it’s up to the web owner to either deliver the content over a CDN or directly from their hosting infrastructure.

While we observed CDN adoption across different types of content, we will look at this data from a different point of view below.

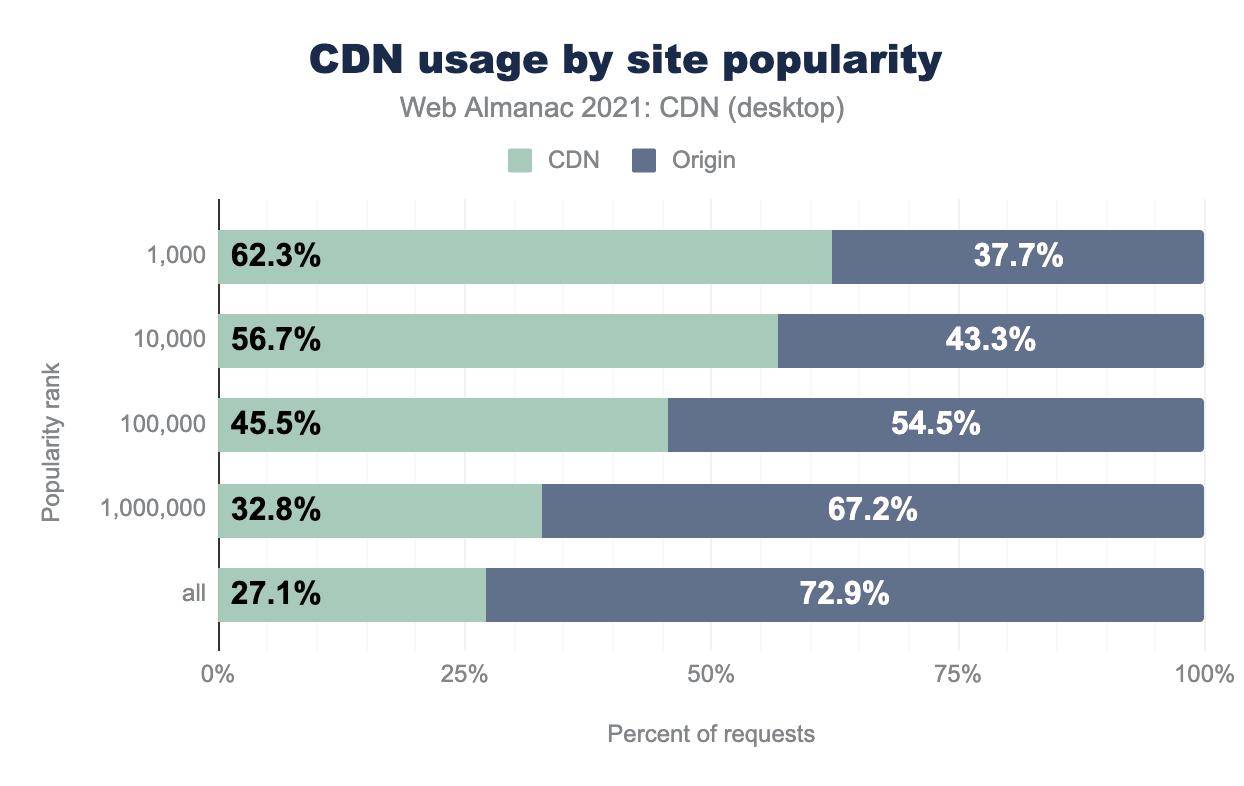

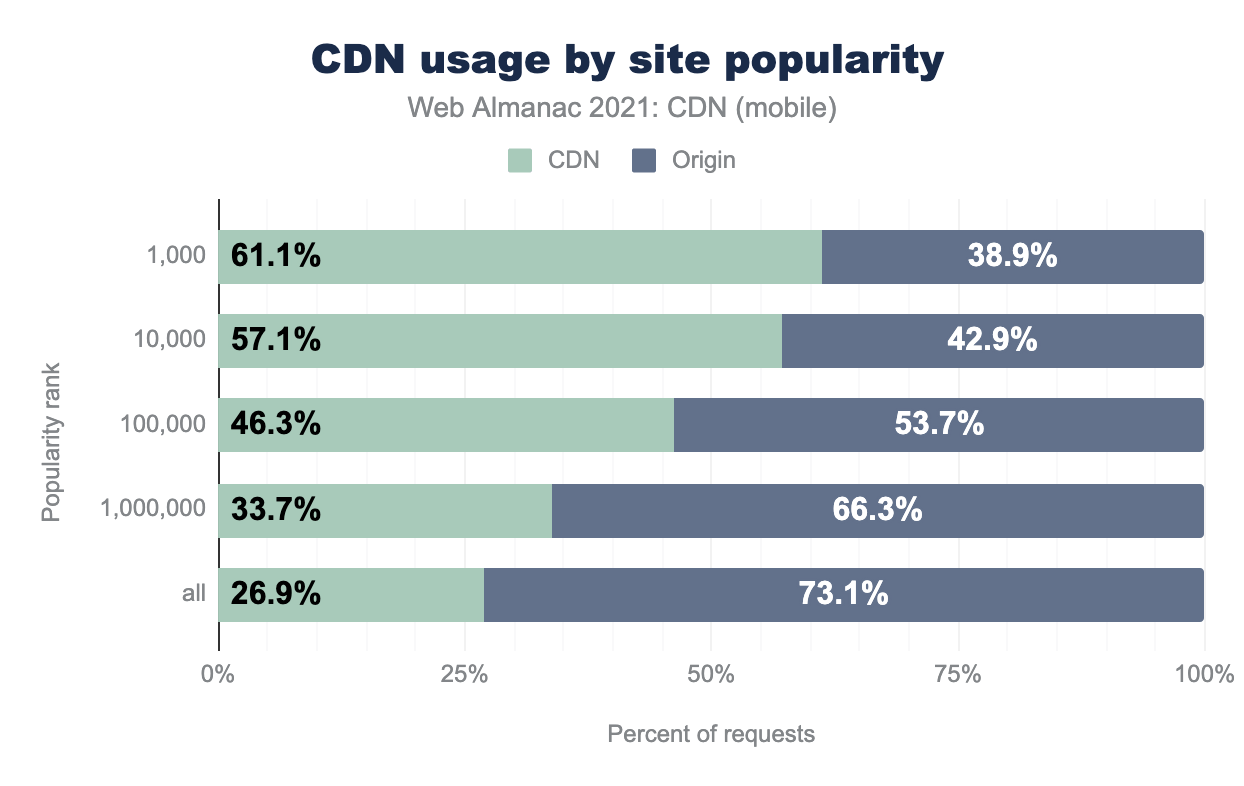

Ranking the websites based on their popularity (sourced from Google’s Chrome UX Report) in the web and then checking for their CDN usage, the top 1,000 contribute to the highest usage of CDN. The top websites are owned by larger companies like Google and Amazon, who contribute to much of the internet traffic we see today, so it’s no surprise that these names make it to the list of top CDN providers in the next section. This also backs the fact about the benefits CDNs bring to the table when operating at scale and having the ability to scale further if needed.

The CDN adoption rate falls below 50% when we look at the top 100,000 websites but the rate of reduction slows down beyond this. For the full data set (which is 6.2 million sites on desktop and 7.5 million on mobile), 27% of these websites use CDN. When you translate that percentage into real number, that’s 2 million mobile websites using CDN! It’s not such a small number when you look at it this way.

But the decreasing percentage of CDN adoption in the low-popularity website end does make sense considering the benefits of CDN (such as caching and TCP connection offload) increases with the number of end users on the web property. Below a certain scale of end-user traffic on a web property, the cost-to-benefit math of a CDN may not work in web property owner’s favor and they might be better off delivering the web content directly from the origin.

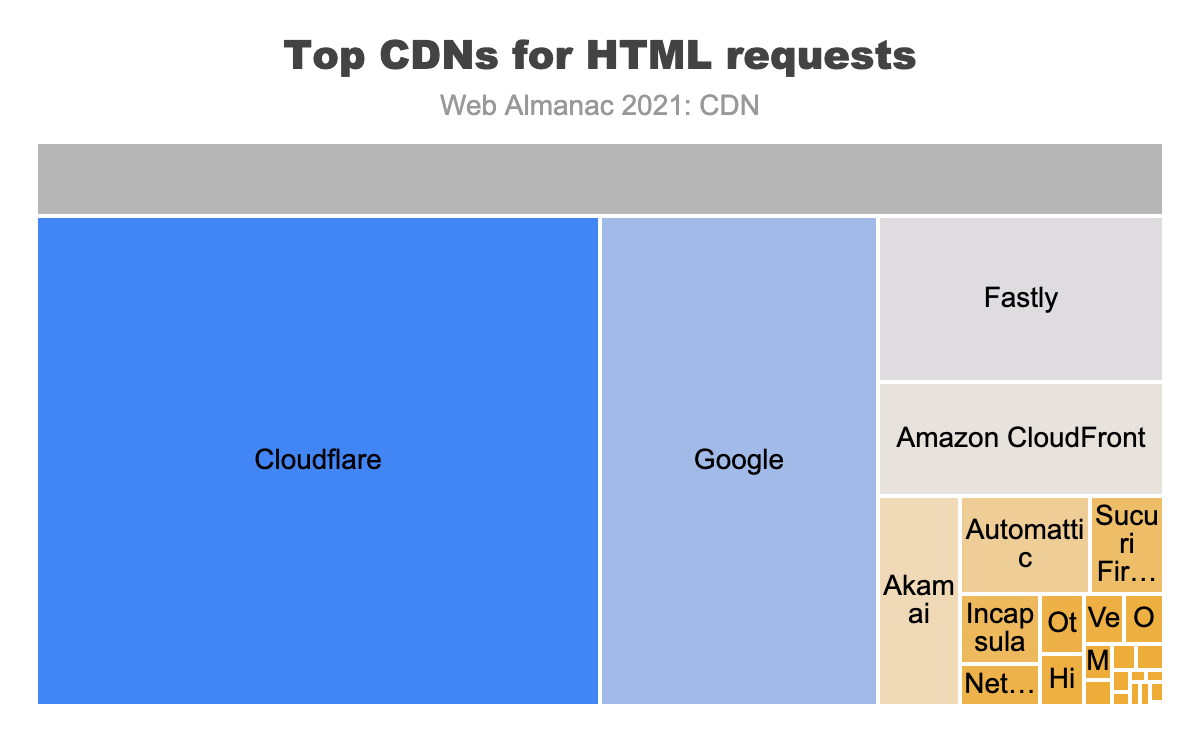

Top CDN providers

CDN providers can be broadly classified into 2 segments:

- Generic CDN (Akamai, Cloudflare, Fastly etc.)

- Purpose-built CDN (Netlify, WordPress etc.)

Generic CDN addresses the mass market requirements. Their offerings include:

- Web site delivery

- mobile app API delivery

- Video streaming

- Serverless compute offerings

- Web security offerings, etc.

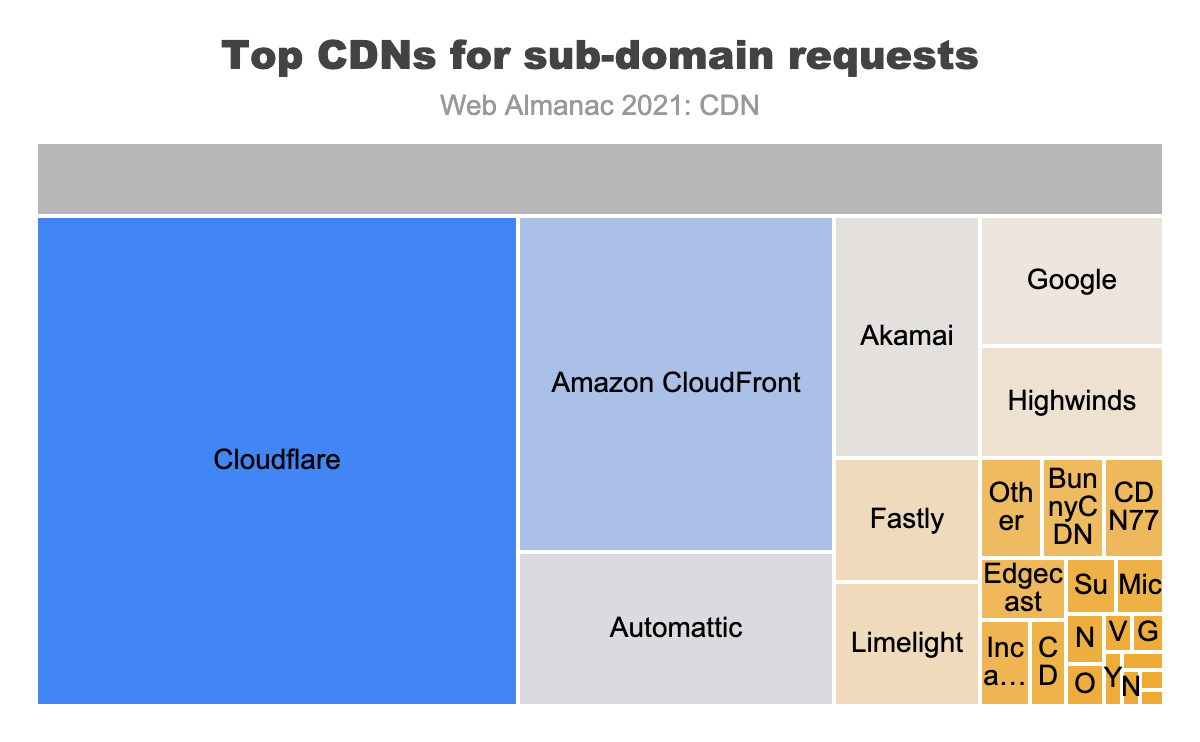

This appeals to a larger set of industries and is reflected in the data. Generic CDNs hold the lion’s share of the HTML and First party subdomain traffic:

CDN providers such as Cloudflare, Fastly, Akamai and Limelight appear in this list of Generic CDN providers. We also see other providers such as Google and AWS. They appear in this list since they offer bundled CDN offerings along with their Cloud hosting services. These bundles help reduce load on the hosting infrastructure and also improves web performance.

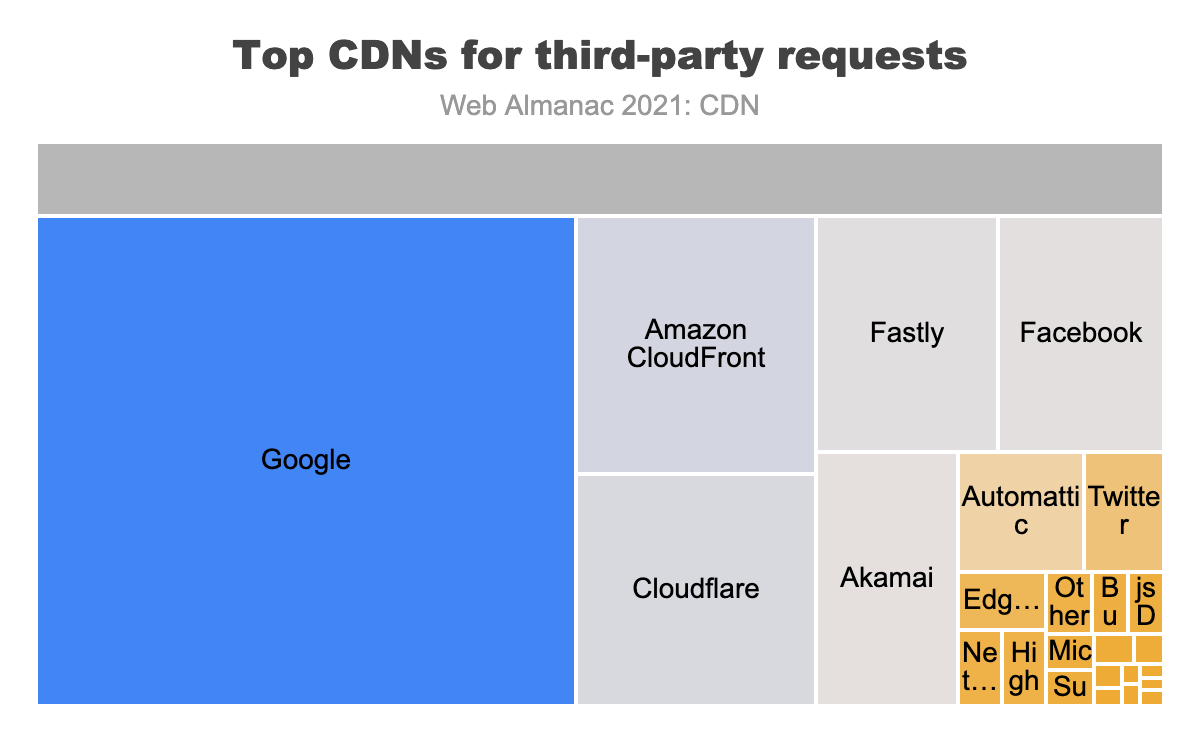

Looking at third-party domains below, a different trend in top CDN providers is seen. We see Google top the list before the generic CDN providers. The list also brings Facebook into prominence. This is backed by the fact that a lot of third-party domain owners require CDNs more than other industries. This necessitates them to invest in building a purpose-built CDN. A purpose-built CDN is one which is optimized for a particular content delivery workflow.

For example, a CDN built specifically to deliver advertisements will be optimized for:

- High input-output (I/O) operations

- Effective management of long tail content

- Geographical closeness to businesses requiring their services

This means purpose-built CDNs meet the exact requirements of a particular market segment as opposed to a generic CDN solution. Generic solutions can meet a broader set of requirements but are not optimized for any particular industry or market.

TLS adoption impact

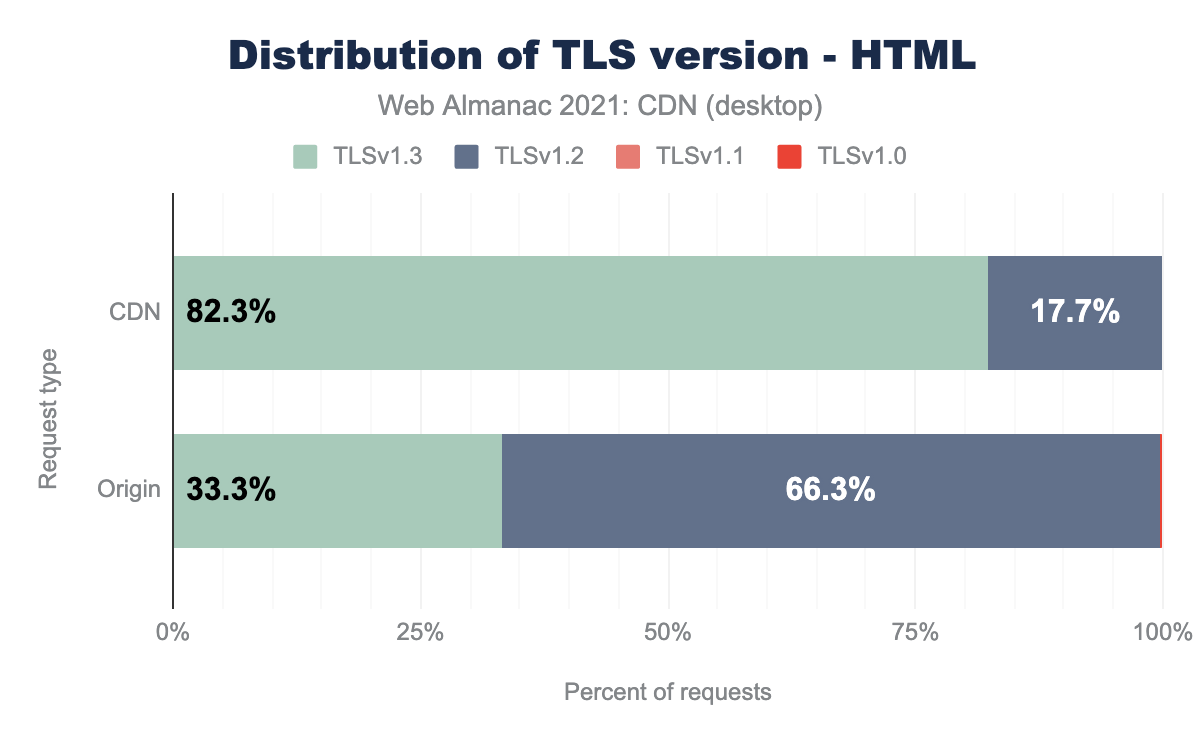

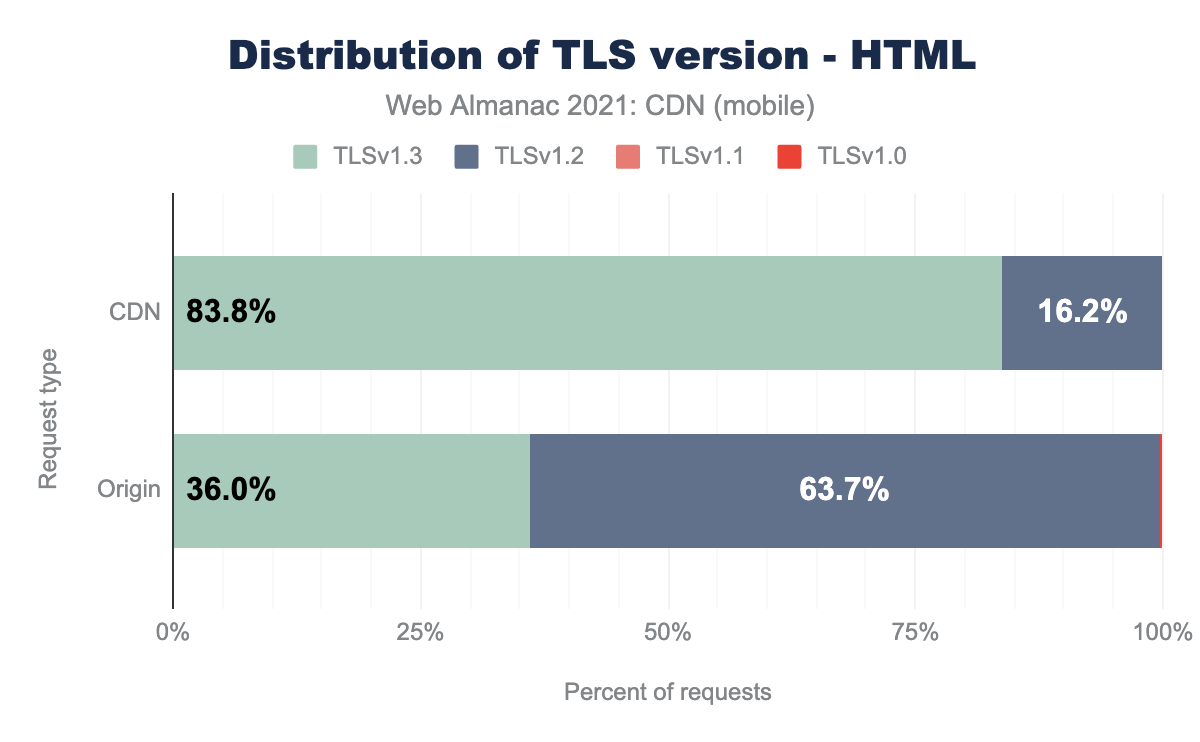

With CDNs set up in the request-response workflows, the end-user’s TLS connection terminates at the CDN. In turn, the CDN sets up a second independent TLS connection and this connection goes from the CDN to the origin host. This break in the CDN workflow allows the CDN to define the end-user’s TLS parameters. CDNs tend to also provide automatic updates to internet protocols. This allows web owners to receive these benefits without making changes to their origin.

We see in the data above that 83% websites on CDNs use TLS 1.3 compared to 33-36% on the origin. That’s a huge benefit of using a CDN. These protocol upgrades also come with minimal to no-effort for web owners. The trend is identical for mobile and desktop websites.

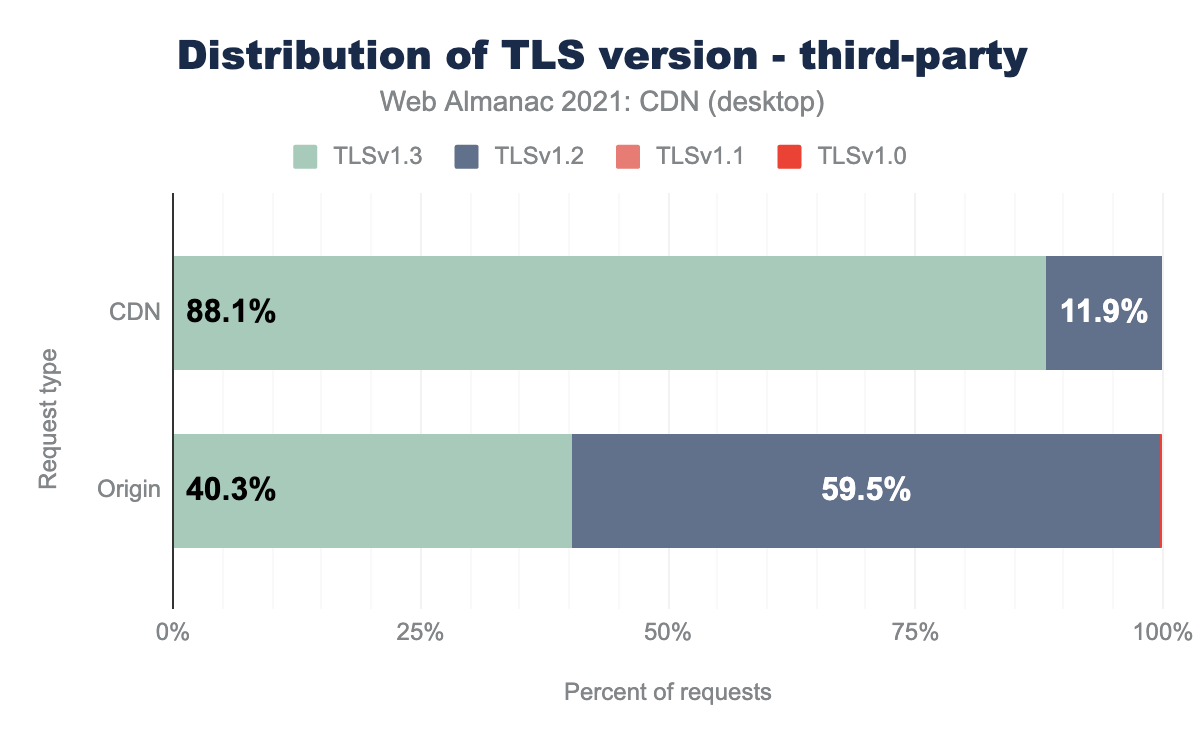

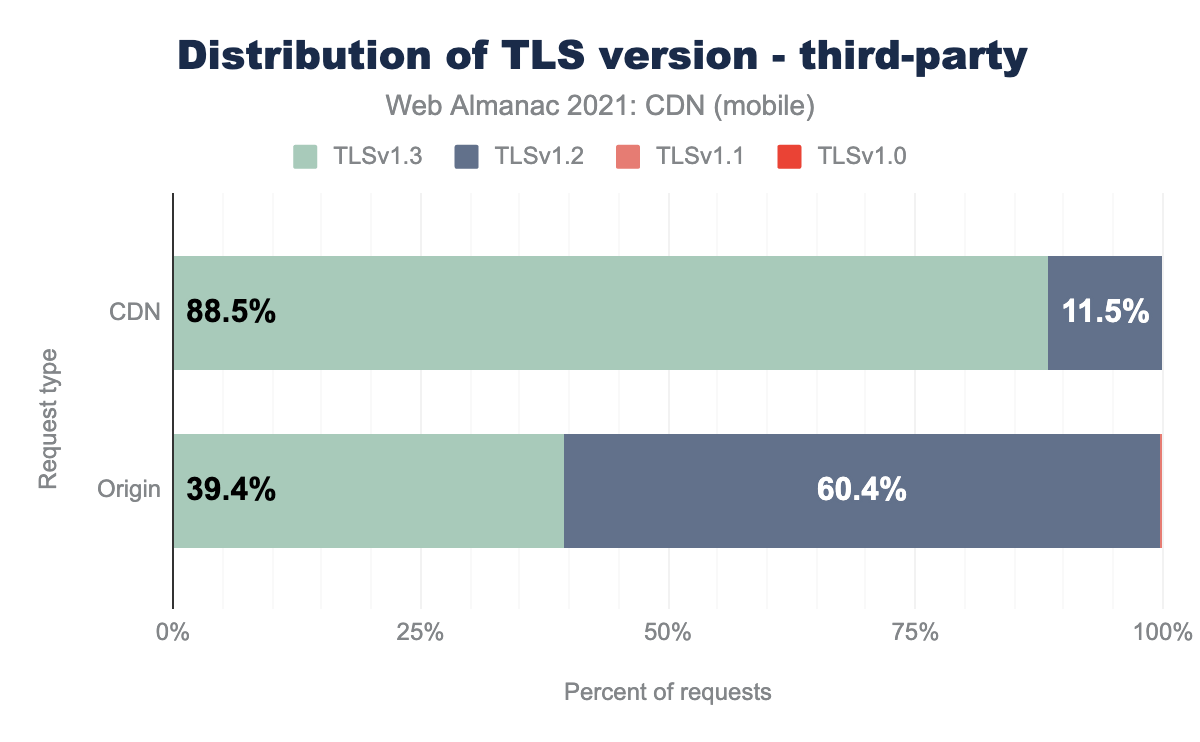

Similar trend is observed for the third-party domains below. These web services with CDNs have better adoption of TLS 1.3 than the ones without for the same reasons.

It is important for third-party domains to be on the latest TLS version for security reasons. With the increase in web attacks, web owners are aware of loopholes that can be exploited with unsecure connections to third-party domains. They will expect equally secure TLS connections which meet the security and performance requirements of their web sites. These expectations enhance the benefits CDNs bring to the table.

TLS performance impact

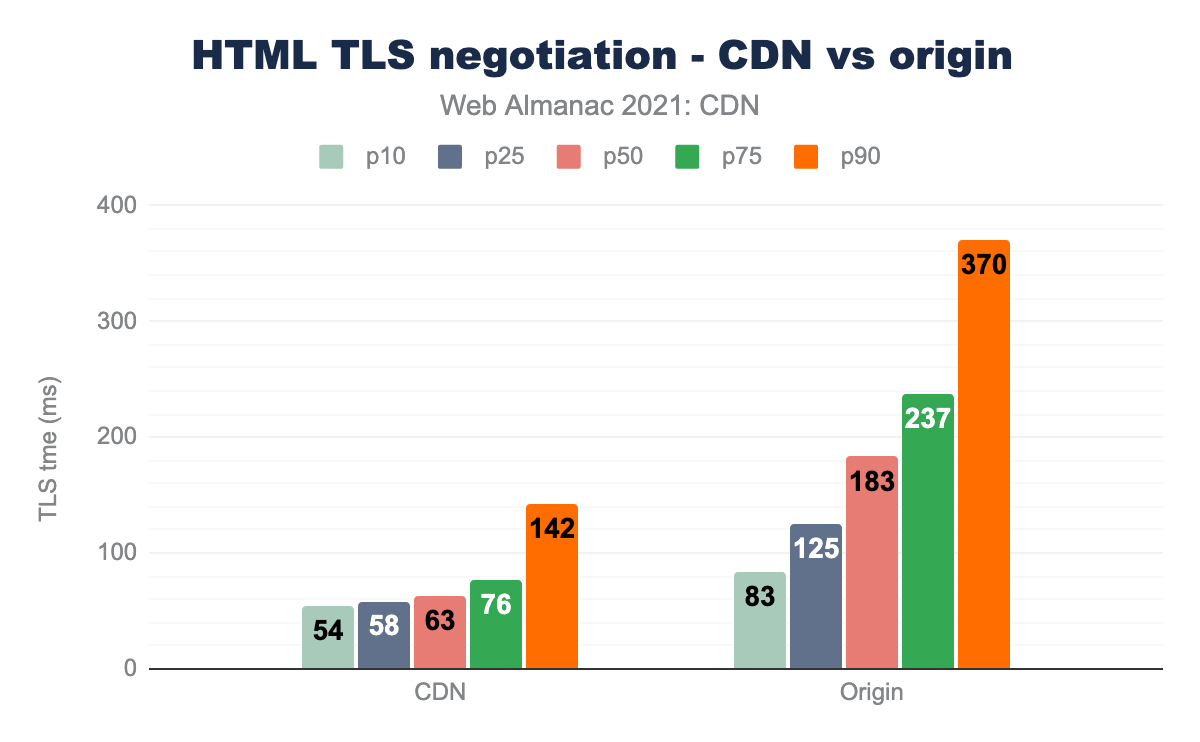

Common logic dictates that the fewer hops it takes for a HTTPS request-response to traverse, the faster the round trip would be. So exactly how much quicker can it be if the TLS connection terminates closer to the end user? The answer: As much as 3 times faster!

CDNs have helped slash the TLS connection times. This is due to their proximity to the end user and adoption of newer TLS protocols that optimize the TLS negotiation. CDNs hold the edge over origin at all percentiles here. At P10 and P25, CDNs are nearly 1.5x to 2x faster than origin in TLS set up time. The gap increases even more once we hit the median and above, where CDNs are nearly 3x faster. 90th percentile users using a CDN will have better performance than 50th percentile users on direct origin connections.

This is quite important when you consider that all sites will have to be on TLS these days. Optimal performance at this layer is essential for other steps that follow TLS connection. In this regard, CDNs are able to move more users to lower percentile brackets compared to direct origin connections.

HTTP/2+ (HTTP/2 or better) adoption

HTTP/2 was introduced with a lot of hype and expectation. This was because the application layer protocol had not been updated since HTTP 1.1 in 1997. Since then, the web traffic trend, content-type, content size, website design, platforms, mobile apps and more have evolved significantly. Thus, there was a need to have a protocol which can meet the requirements of the modern-day web traffic and that protocol was realized with HTTP/2, and then further improved with the more recent HTTP/3.

However, the implementation challenges of HTTP/2 discouraged adoption. In addition, the net performance gains which can be expected with these changes was also not clear. Challenges repeated with the introduction of HTTP/3.

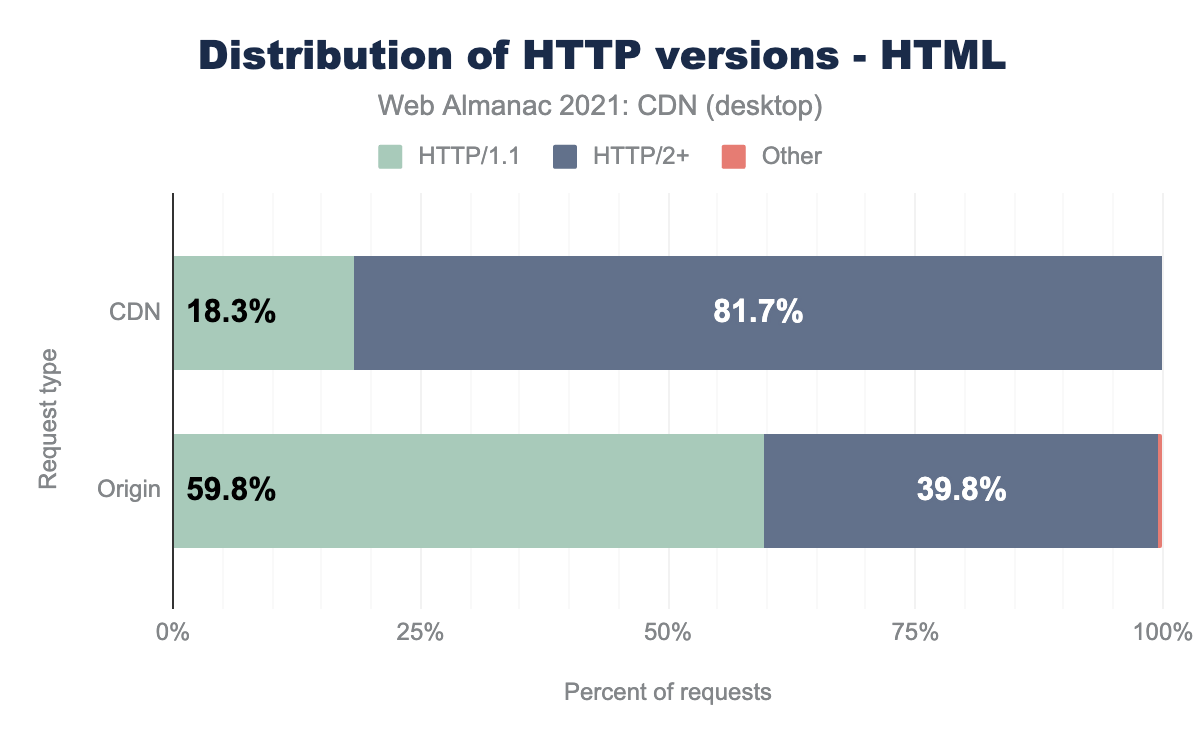

This was where the CDNs being the intermediary can help in bridging the challenge of HTTP/2 implementation for web owners. An HTTP/2 connection terminates at the CDN level, and this provides web owners the ability to deliver their website and subdomains over HTTP/2 without the need to upgrade their infrastructure to support it—the exact same reasons and benefits we saw for newer TLS versions.

CDNs act as the proxy to bridge the gap by providing a layer to consolidate hostnames and route traffic to relevant endpoints with minimal change to their hosting infrastructure. Features like prioritizing content in the queue and server push can be managed from the CDN’s side and a few CDN’s even provide hands-off automated solutions to run these features without any inputs from website owners, thus providing a boost to HTTP/2 adoption.

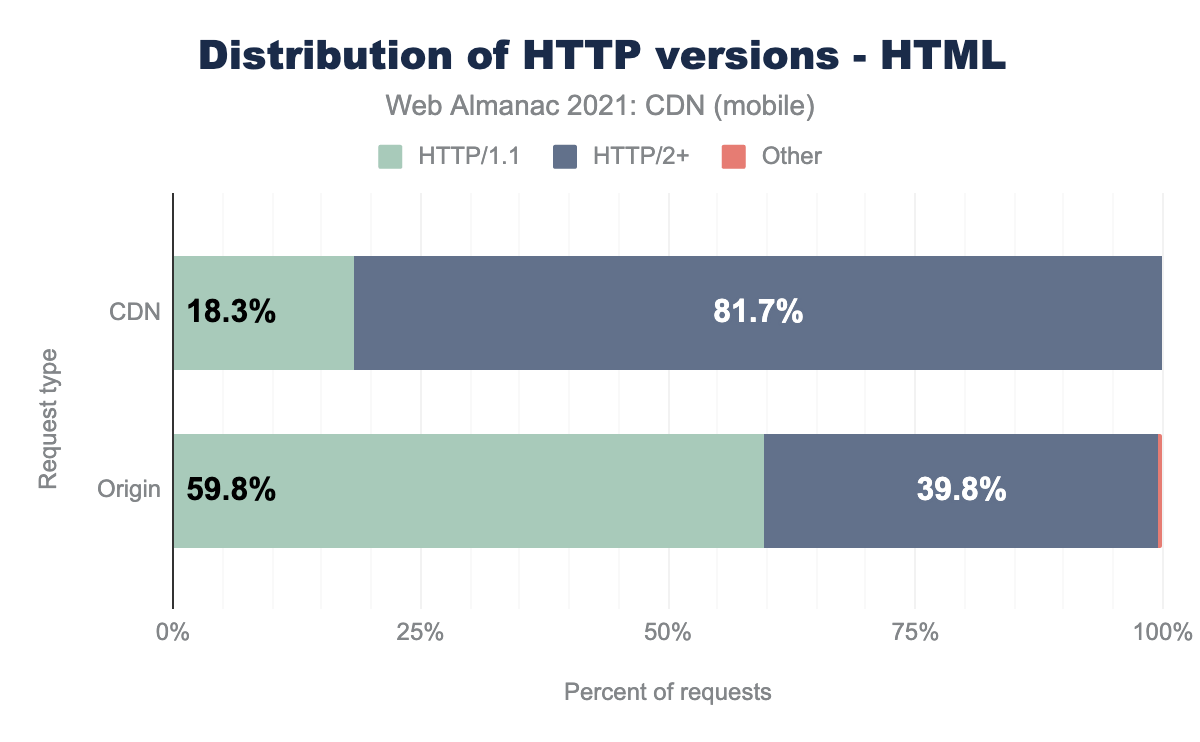

The trend cannot be clearer than what the graph shows below. There is high HTTP/2+ adoption by domains on CDNs compared to the ones not using a CDN.

Back in 2019, the origin domains had 27% adoption of HTTP/2 compared to 71% adoption on CDN. While we see in desktop sites that there is about a 14% increase in origins supporting HTTP/2+ in 2021, domains on CDNs have maintained that lead with a 15% increase. This gap is a bit less when we look at mobile sites, where domains using a CDN have a slightly lower HTTP/2+ adoption compared to desktop sites.

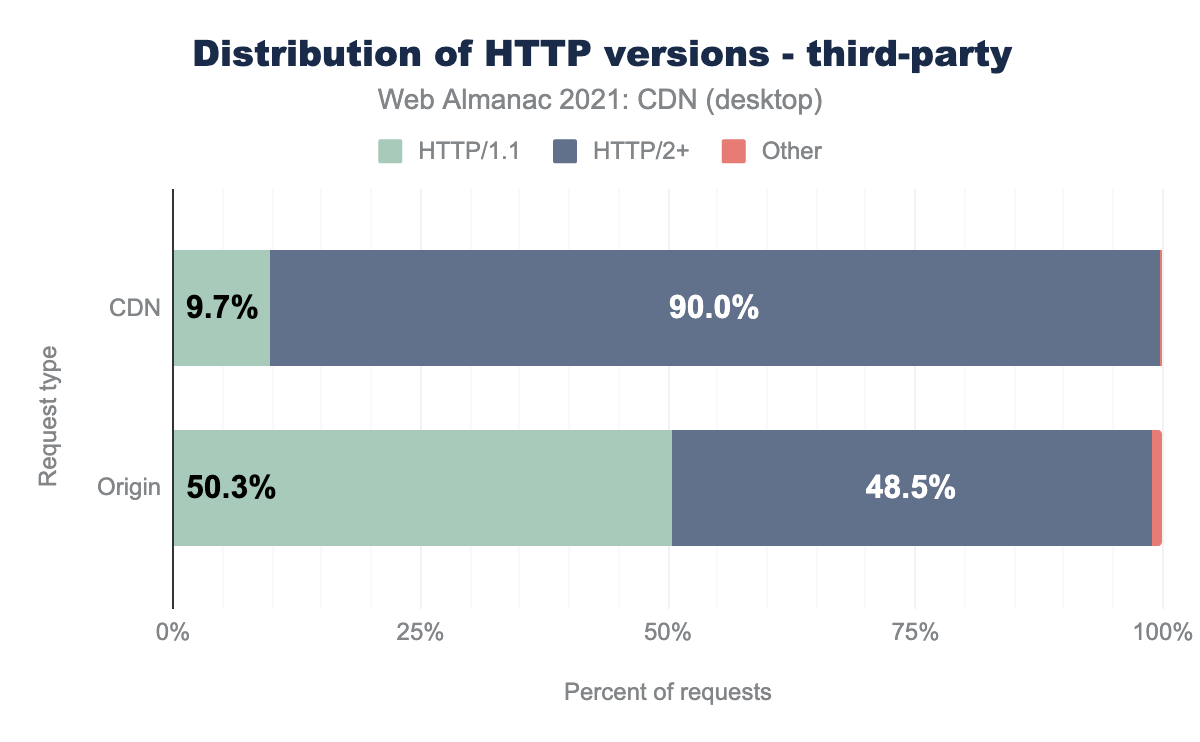

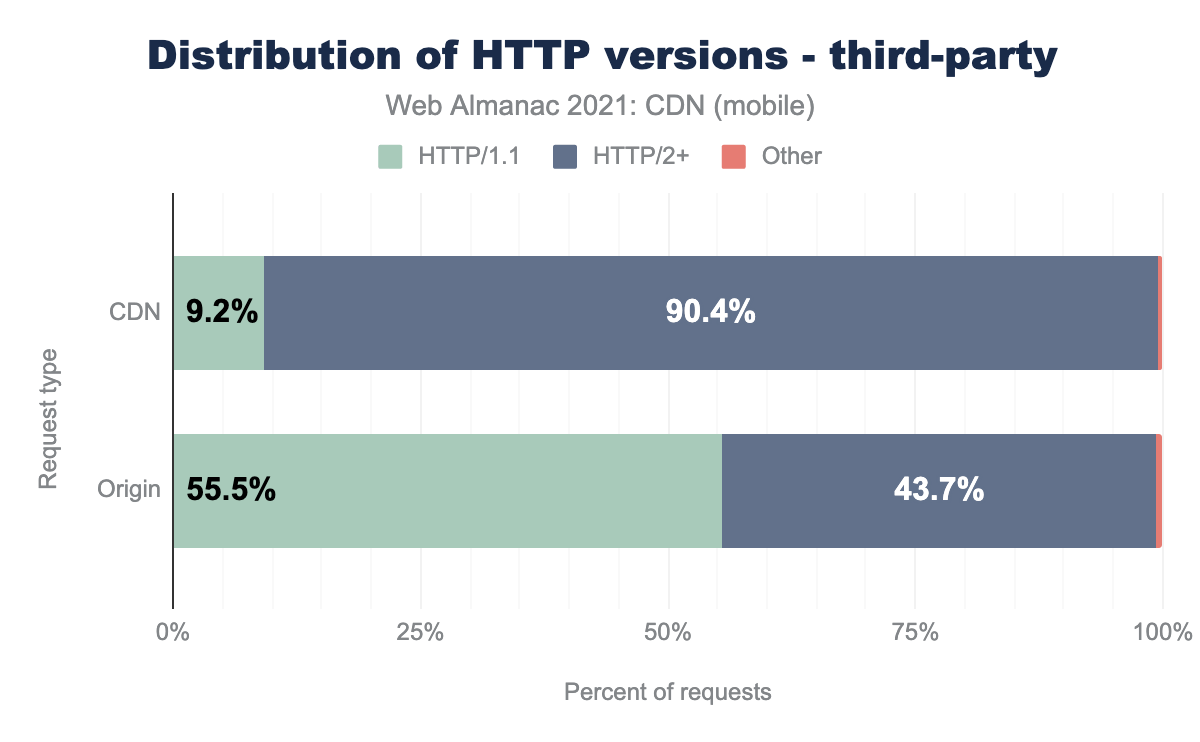

Looking at third-party domains supporting newer protocols, we see an interesting trend of higher adoption of HTTP/2+protocols compared to first-party domains. This makes sense, considering the fact that most of the top third-party domains use purpose-built CDNs and thus have more control on the content development and content delivery. Additionally, third-party domains need to have consistent performance across all network conditions, and this is where HTTP/2+ adds value by mixing in other protocols like UDP (used by HTTP/3) along with traditional TCP connections.

Back in 2019, Uber did an experiment to understand how UDP along with TCP (aka QUIC, the transport layer of HTTP/3) can help deliver content with consistent performance and overcome packet loss in highly congested mobile networks. The results of this experiment documented in this blog post throws valuable insights into the demographic where HTTP/3 can help. Over time, this trend will trickle down and we should see web owners adopting HTTP/3, especially with mobile network traffic having a higher contribution to the total internet traffic.

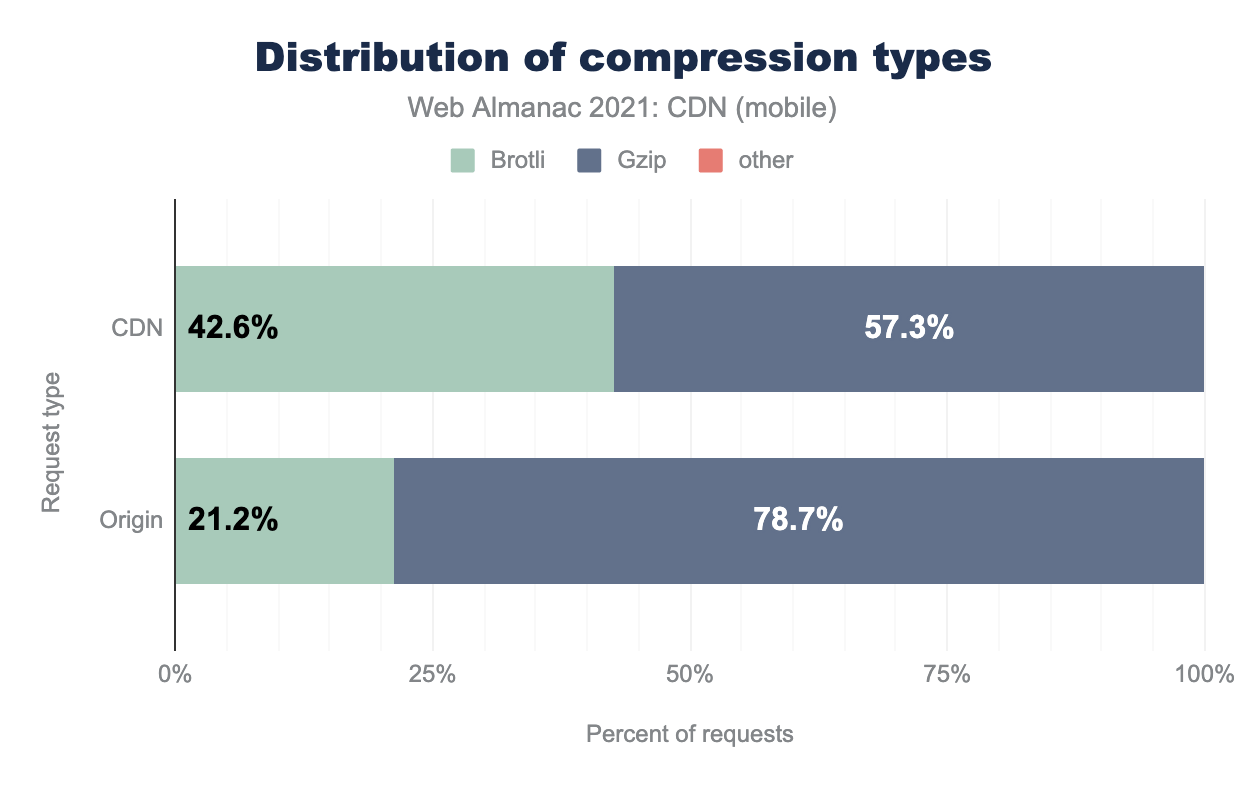

Brotli adoption

Content delivered over the internet employs compression to reduce the payload size. A smaller payload means it’s faster to deliver the content from server to end user. This makes websites load faster and provide a better end-user experience. For images, this compression is handled by image file formats like JPEG, WEBP, AVIF, etc. (refer to the Media chapter for more on this). For textual web assets (such as HTML, JavaScript, and stylesheets) compression was traditionally handled by a file format called Gzip. Gzip has been in existence since 1992. It did a good job of making text asset payloads smaller, but a new text asset compression can do better than Gzip: Brotli (refer to the Compression chapter for more information).

Similar to TLS and HTTP/2 adoption, Brotli went through a phase of gradual adoption across web platforms. At the time of this writing, Brotli is supported by 96% of the web browsers globally. However, not all websites compress text assets in Brotli format. This is because of both lack of support and of the longer time required to compress a text asset in Brotli format compared to Gzip compression. Also, the hosting infrastructure needs to have backward compatibility to serve Gzip compressed assets for older platforms which do not support the Brotli format, which can add complexity.

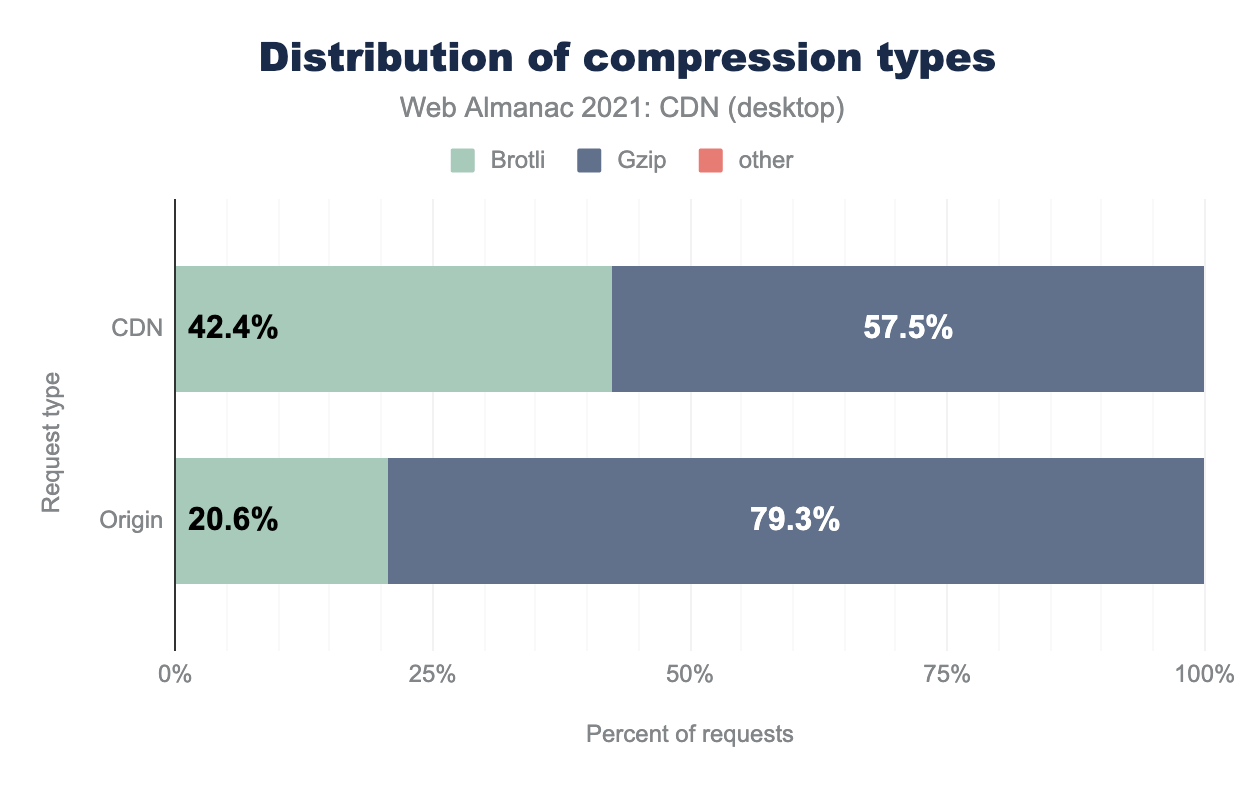

The impact of this is observed when we compare websites which are using CDN against the ones not using CDN.

On both desktop and mobile platforms, we see that CDNs are delivering twice as many text assets in Brotli, compared to domains delivered from origin. From the CDN adoption section covered earlier, 73% of the domains serving sites are on CDNs and these can all benefit from the Brotli compression. By offloading the computational load of compressing a text asset in the Brotli format to CDNs, website owners need not invest resources for hosting infrastructure.

However, it is at the web property owner’s discretion whether to use Brotli compression on their CDNs or not. Compared to 95% of the web browsers globally which support Brotli compression, even with CDNs in place, less than half of all the text assets are delivered in Brotli format—so there is clearly space for this adoption to improve.

Conclusion

There are limitations to the insights we can deduce about CDNs from the outside, since it is hard to know the secret sauce powering them behind the scenes. However, we have crawled the domains and compared the ones on CDNs against those who are not. We can see that CDNs have been an enabler for websites to adopt new web protocols, from the network layer to the application layer.

This impact is universal, with similar adoption rates across mobile and desktop: from using the latest TLS versions to upgrading to the newest HTTP versions (like HTTP/2, HTTP/3) to using the Brotli compression. What stands out is the depth of this impact and the sizable lead the CDN domains have built relative to non-CDN domains.

This role of CDNs is highly valuable and this will continue to be the case. CDN providers are also a key part of the Internet Engineering Task Force, where they help shape the future of the internet. They will continue to play a key role aiding the internet-enabled industries to operate smoothly, reliably and quickly.